One year ago this month, Apple unveiled the AirTag, a shiny, half-dollar-sized coin with a speaker, Bluetooth antenna, and battery inside, which helps users keep track of their missing items. Attach an AirTag to your purse, keys, wallet, or even your car, and if you lose it, the device will ping every nearby Apple product with Bluetooth turned on to triangulate its location. Those devices send its location back to you on a map, showing where the AirTag has been and its current location.

Police records reviewed by Motherboard show that, as security experts immediately predicted when the product launched, this technology has been used as a tool to stalk and harass women.

Videos by VICE

Motherboard requested records mentioning AirTags in a recent eight month period from dozens of the country’s largest police departments. We obtained records from eight police departments.

Of the 150 total police reports mentioning AirTags, in 50 cases women called the police because they started getting notifications that their whereabouts were being tracked by an AirTag they didn’t own. Of those, 25 could identify a man in their lives—ex-partners, husbands, bosses—who they strongly suspected planted the AirTags on their cars in order to follow and harass them. Those women reported that current and former intimate partners—the most likely people to harm women overall—are using AirTags to stalk and harass them.

In one report, a woman called the police because a man who had been harassing her had escalated his behavior, and she said he’d placed an AirTag in her car. The woman said the same man threatened to make her life hell, the report said.

Motherboard is excluding specific details from these reports so as not to identify victims, for their safety.

Most cases involved angry exes; one woman called to report that her ex had slashed her tires and left an AirTag in the car to watch her. A woman in another police report said she’d found AirTags attached to her car multiple times, and knew it was her ex, who has a history of assault. She said she knew it was him because he was showing up to her locations at the same time as her.

In another police report, a woman said she started noticing something beeping inside her vehicle every time she left her house; she found an AirTag in her car and confronted an ex who admitted to putting it there to see if she was “cheating.”

Seeing exes mysteriously appear wherever and whenever they went out was a major red flag for several women who made these reports. One woman kept spotting her ex following her. At one point, he found and cornered her. She took her car to a mechanic, who found an AirTag in it.

Multiple women who filed these reports said they feared physical violence. One woman called the police because a man she had a protective order against was harassing her with phone calls. She’d gotten notifications that an AirTag was tracking her, and could hear it chiming in her car, but couldn’t find it. When the cops arrived, she answered one of his calls in front of the officer, and the man described how he would physically harm her. Another who found an AirTag in her car had been wondering how a man she had an order of protection against seemed to always know where she was. The report said she was afraid he would assault or kill her.

One woman came into a police station to report that she was getting notifications for weeks about AirTags nearby, and had found multiple AirTags mounted under her car. She suspected a man who had been violent toward her before, who was now appearing wherever she went.

Have you been a victim of harassment using AirTags? We’d love to hear from you, and you can remain anonymous. Contact Samantha Cole on the secure messaging app Signal at +1 646 926 1726, or email samantha.cole@vice.com.

Not all cases involved exes; in some, the women were still in relationships or marriages with the men stalking them, and became physically violent when they were confronted about the AirTags.

The overwhelming number of reports came from women. Only one case out of the 150 we reviewed involved a man who suspected an ex-girlfriend of tracking him with an AirTag.

AirTags have also attracted some attention as a potential vector for human trafficking. One of the records said the caller “believed she’s being tracked to become a victim of a scheme she observed on Instagram.” On TikTok last year, a woman went viral for posting a video holding an AirTag with the caption, “This is something you see in movies 🥺😣🤯😱 #fyp #sextrafficking.” The video provides no context beyond her finding the AirTag behind her license plate. Police themselves have spread the notion that AirTags are being used by sex traffickers, but there’s no evidence that this is happening.

Of the 150 total police reports mentioning AirTags that these departments provided, less than half mentioned AirTags as part of robberies or thefts—the sort of stories where someone had an AirTag in their purse or attached to a bike or car that was subsequently stolen. Several involved people who got AirTag notifications on their phones but couldn’t find a device anywhere; some of these reports mention the callers saying they’d heard about the danger of AirTags on the news. (One said she “wasn’t sure” if this was related to “human trafficking” or not, and had no one to suspect, but called the police when she received a notification.)

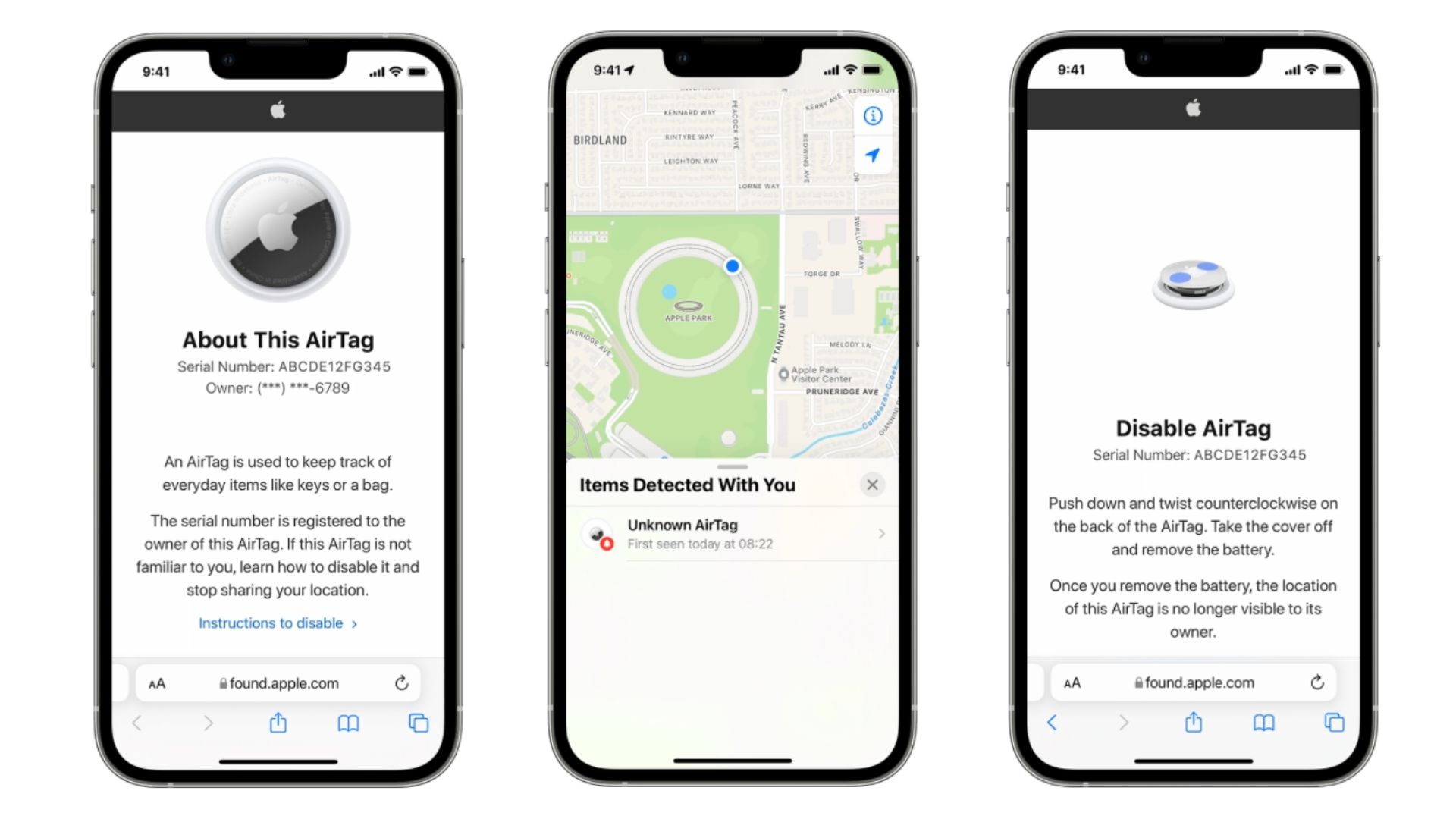

AirTags have always implemented a notification feature that alerts people with iPhones if an AirTag is traveling with them; anyone not using an iPhone or Apple device, however, would never know.

“That was a completely ridiculous way to launch a new device, without having taken into account its use in a domestic violence situation,” Eva Galperin, the director of cybersecurity at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, told me. “But specifically, the blind spot that Apple had was people who live outside of the Apple ecosystem.”

We’ve known for years that abusive domestic partners sometimes use software installed on their targets’ phones to track and control them. AirTags are different because they’re widely advertised by one of the biggest consumer tech companies in the world, cheap at only $29, and easy to plant inconspicuously on a car or in a bag.

“Stalking and stalkerware existed before AirTags, but Apple made it cheaper and easier than ever for abusers and attackers to track their targets,” Albert Fox Cahn, executive director at the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project, told Motherboard. “Apple’s global device network gives AirTags unique power to stalk around the world. And Apple’s massive marketing campaign has helped highlight this type of technology to stalkers and abusers who’d never otherwise know about it.”

A handful of reports of people being tracked with these devices have attracted national attention. In December, a woman found an AirTag attached to her car, and suspected someone put it there to try to steal the vehicle. In January, a Philadelphia woman said she’d been followed from afar by someone with an AirTag. That same month, police in Dearborn, Michigan said that they’d seen an uptick in reports from people who received AirTag notifications, with the caveat that at least some of those were likely people getting notifications from nearby AirTags that weren’t actually targeting them.

To try to stress-test Apple’s safety features on AirTags, journalists at the Verge and the New York Times have experimented with AirTags in their own lives, using controlled environments to replicate the stalking scenarios that security experts have warned the public about. These stories didn’t shy away from the potential use of AirTags as a tool of abuse, but most coverage of AirTags in the real world, so far, has focused on AirTags as tools for car thieves.

The stories that haven’t yet appeared in the news are those of domestic violence victims. It’s difficult for targets of such intimate partner violence as stalking or harassment to come forward publicly; exiting such a situation is incredibly dangerous, before even bringing in the complications posed by talking to a hometown reporter about it. Police reports obtained by Motherboard, though, show that while the use of AirTags as a tool by strangers that’s hyped on social media appears to be rare, their use as a tool of control by abusers against women is not.

AirTags are far from the only physical location trackers on the market, and any of these can be used for malicious purposes. In recent years, however, they’ve gotten more convenient and user-friendly for a mass market. Tile, a tracker similar to AirTags, announced last month that it was implementing new anti-stalking features in its app.

Location stalking is “as old as GPS technology itself,” Mary Beth Becker-Lauth, domestic violence community educator at the nonprofit organization Women’s Advocates, told me. But historically it’s taken some technical knowledge to implement against another person. “Until fairly recently, the women (and they were always women) who’d come to our program for support while being stalked/tracked had an abuser/stalker who worked in IT or who was highly tech-savvy,” she said.

AirTags, being a device you can just tape to the underside of a car or pop into a purse, are more insidiously easy for abusers to use. Apple’s “it just works” ethos is part of the appeal of AirTags, too, but in this case, it’s exploited to its worst ends.

“The fact that most women who are finding AirTags on their person know who might have put them there is right in line with demographic research on stalking,” Becker-Lauth said. “Nearly three out of every four stalking victims know their stalker, and the most common relationship between a stalking victim and their stalker is a current or former intimate partner. So it makes sense that these women have someone they can point to immediately and say ‘This sounds like something he would do.’”

“Stalking and stalkerware existed before AirTags, but Apple made it cheaper and easier than ever for abusers and attackers to track their targets”

In a response to a request for comment about these reports, Apple sent a link to its latest company blog post in February, outlining recent security updates.

“AirTag was designed to help people locate their personal belongings, not to track people or another person’s property, and we condemn in the strongest possible terms any malicious use of our products,” the blog post says. “Unwanted tracking has long been a societal problem, and we took this concern seriously in the design of AirTag. It’s why the Find My network is built with privacy in mind, uses end-to-end encryption, and why we innovated with the first-ever proactive system to alert you of unwanted tracking.”

The company also published instructions for what to do if you find out an AirTag is tracking you, but domestic abuse experts say that confronting an abusive partner or ex or disabling their tracking can be dangerous.

Perhaps more telling is the way Apple has responded to security concerns with piecemeal, reactive updates to the technology. Apple launched an Android app that will notify users of AirTags in December, but users have to learn about and then install the app, then allow it permission to work in the background—steps many people won’t follow through with. In June 2021, three months after the product launched, it shortened the window for a feature where the AirTag would chime if it was separated from its owner; originally, it was three days, which they changed to between eight and 24 hours—ideally, alerting a stalking target to the device in their vicinity. In February, following the New York Times’ experiment, Apple announced even more security features, including warnings at setup that tracking people without their consent is a crime, more precise tracking of the AirTag for the person being tracked, and louder chimes.

The fact that there are so many reports from people about AirTag stalking means Apple’s security measures, such as the notifications, are working as intended, said Galperin. “It’s not that somebody has randomly found an AirTag. It’s that the anti-stalking mitigations that Apple has implemented are finally working, and the results are that some smaller subset of those people are then going to police,” she said. “So, yes, we did understand from the very beginning that this was going to be a major problem. But part of it I think is just reflected in the fact that stalking is a major problem. And that having the AirTag alert go off is actually something that a person can bring to the police as solid evidence, which sometimes they otherwise do not have.”

Some experts said that what the company has done is still not enough. “This is too little too late,” Cahn said. “These gimmicks do little to prevent AirTags from being misused, and they often only notify targets once the damage is done and their location has been tracked. There’s no technical fix that can prevent AirTags from being abused. As long as Apple continues to sell a cheap, easily-hidden tracking device, stalkers will continue to use it. The only solution is to stop selling and supporting AirTags. This product is far too dangerous to stay on the market.”

“I wish Apple had been more proactive and done troubleshooting to reduce the risk of bad actors before this product was released,” Becker-Lauth said. “But honestly, no trackable technology is going to be completely safe.”

If people aren’t going to stop using these devices for harassment, it may be up to device manufacturers to figure out how to make them safer. Last week, industry outlet 9to5Google spotted a new feature Google may be working on: “Unfamiliar device alerts” and a “Unfamiliar Tag Detected Notification” in the safety settings for Android devices.

Galperin told me that the next step for device manufacturers is to set a safety standard for the industry to follow.

“The thing that I am most looking forward to is seeing the makers of physical trackers agree on a standard that can then be implemented in operating systems, so that people have detection of trackers working in the background all the time, automatically, no matter what kind of phone that they have,” she said. “I think that’s the only reasonable and effective mitigation to this mess we’re in.”

And people who go to the police to report being stalked or harassed should have better resources to protect themselves from abusers if they do go to the police. In most of these reports, when a woman reported a stalker, the responding officer either offered them a domestic violence hotline phone number, or advised them to file (or re-file) for a protective order. Some of the officers wrote that they’d heard of AirTags being used to steal from people before, but others seemed to not understand what an AirTag was or how to disable it.

“Police often have no idea how to respond to AirTags, but even if they did, that wouldn’t be a solution,” Cahn said. “We can’t arrest our way out of Apple’s mess. In many jurisdictions, it’s unclear if using AirTags is a crime, and even if it is, mass incarceration is a terrible solution.”

Laws against tracking someone’s location vary from state to state, either as part of stalking laws or specifically in terms of tracking a car without the owner’s consent.

“At the very least, these women should be believed. The safety of victim-survivors from control and violence does not appear to be a priority for many of the police departments in this country,” Becker-Lauth said. “We should be taking these women’s experiences so, so seriously, because when they tell a police officer or domestic violence advocate that they are being stalked, what they’re really saying is that their life is in danger, usually because of the person doing the stalking.”

Timothy Marchman contributed reporting to this story.