For our annual photo issue we reached out to 16 up-and-coming photographers and asked them which photographer inspired them to pursue the medium. Then we approached their “idols” to see if they would be willing to publish work in the issue as well. What was provided, we think, creates a unique conversation about the line of influence between young artists and those more established in their careers. This post features an interview with Luisa Dörr and her chosen idol, Sage Sohier, and an explanation of each of their bodies of work.

In April 2014, Luisa Dörr was on assignment to photograph the Young Miss Brazil contest. There, she noticed Maysa Martins, an 11-year-old in the crowd. Maysa told Dörr that she hoped, one day, to be Miss Brazil. But her aspiration came with a catch. The competition was divided into two categories: one for white contestants, and another for people of color. Though around 50 percent of Brazilians identify as “black” or “mixed race,” racism remains prevalent throughout the country. A few months after Young Miss Brazil, Maysa’s mother contacted Dörr, asking if she’d shoot her daughter’s personal modeling portfolio. Dörr agreed to do it for free. Six months later, Maysa was crowned Young Miss São Paulo Black Beauty, winning a separate and smaller local pageant with the same racial divisions as Young Miss Brazil. Unfortunately, the nationwide tournament’s creator disappeared, and it ceased to exist. But in 2017, Maysa was invited onto a Brazilian television program to walk the runaway in front of a live jury. She received a modeling contract and the chance to tell her story.

Videos by VICE

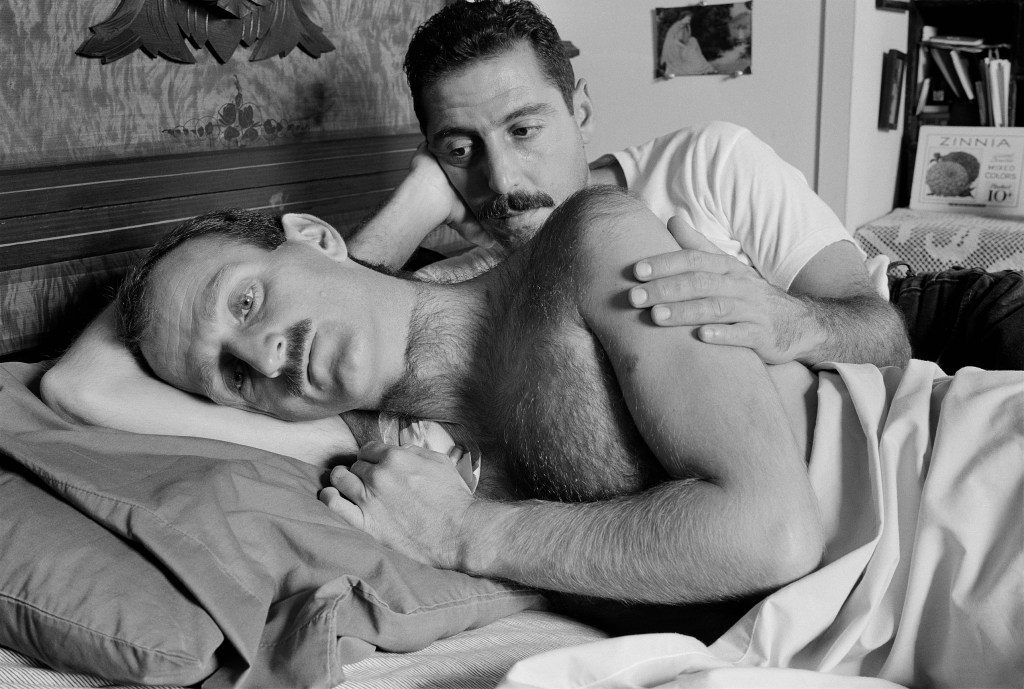

When Sage Sohier began photographing gay and lesbian couples in the mid 1980s, she had a personal connection to the topic: Her dad, a World War II veteran and a lawyer, had divorced her mother but never remarried, and soon young men—usually introduced as “colleagues from work”—replaced the young women who occasionally accompanied him. Sohier figured out that her dad was gay in the mid 1970s. From middle age on, he had a number of live-in boyfriends, but he never “came out”—even to his family. Originally published in 2014, At Home with Themselves: Same-Sex Couples in 1980s America, Sohier’s intimate, portraits of committed same-sex couples during the AIDS epidemic, does not conform to the stereotypes of gay promiscuity prevalent in that era. Sohier says that it was her “ambition to make pictures that challenged and moved.” Here, for the first time, are some photographs that were not included in her book.

Luisa Dörr: Where did it all begin for you? Why did you decide to become a photographer? Sage Sohier: When I was young, I was entranced by photography—it was permission to observe, and it also seemed to provide a valid excuse to go off and explore on my own, away from my family. Both my mother and father were theatrical in different ways, and so being an observer was both an available role and also one that suited my somewhat reserved character.

I taught myself how to print in the darkroom in high school, and in college, I photographed for the school newspaper. But when I took my first photography course, during my second year in college, I realized for the first time that making photographs could be as powerful as writing fiction, and I knew it was something I wanted to pursue. I had considered trying to be a writer, but I was much too restless to sit at a typewriter for long, and I found that interacting with people out in the world was fascinating and took me out of myself in a good way.

Your work focuses on people in their environments. Why do these topics engage you, and how do you choose to approach them as a visual storyteller?

I think that people’s houses—what they collect, what they put on their walls—reveal a lot about them. I also love complex images; it’s a challenge to see how much I can pack into a picture and still make it work.

Your work features a mix of more candid photographs and portraits. How do you approach a story visually?

I try to make my portraits as psychologically interesting as possible. I like to show relationships between people—both their intimacy and their ambivalence—and I like to show people in situations where you might not otherwise see them—in their bedrooms, in their basements, and so on.

What is important to you when creating a portrait? Can you tell me a little bit about the process, if you are looking for the person’s trust versus some discomfort?

I spend a lot of time talking to people or emailing back and forth with them before I start photographing, to get a sense of who they are and to begin to imagine the kind of picture I might be able to make of them. I certainly want to gain their trust, and being able to share my website with people before I photograph them has been a great help in this regard; I used to carry a box of pictures around to show people the kinds of pictures I took. I try to make the process of photographing someone a collaborative effort. Their suggestions for situations we might try are often better than anything I could come up with. You can’t be too polite, though; you really have to go for the picture you want. Sometimes this means you have to push people a bit out of their comfort zone. If you can do it with enough enthusiasm and gratitude, it usually ends up with everyone feeling OK.

Do you have a mantra or philosophy for your work?

When I am driving or walking to someone’s house, I give myself a pep talk, which usually includes something like: “Don’t settle. Push for that one extra element that will give the picture the possibility of being extraordinary. Always stop and ask yourself, What else? What else does the picture need?“

![r.bliss x MOM publishing: "LOVE" [supplied]](https://www.vice.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2024/05/1717114913901-screenshot-2024-05-07-at-21037-pm-scaled.jpeg?w=1024)