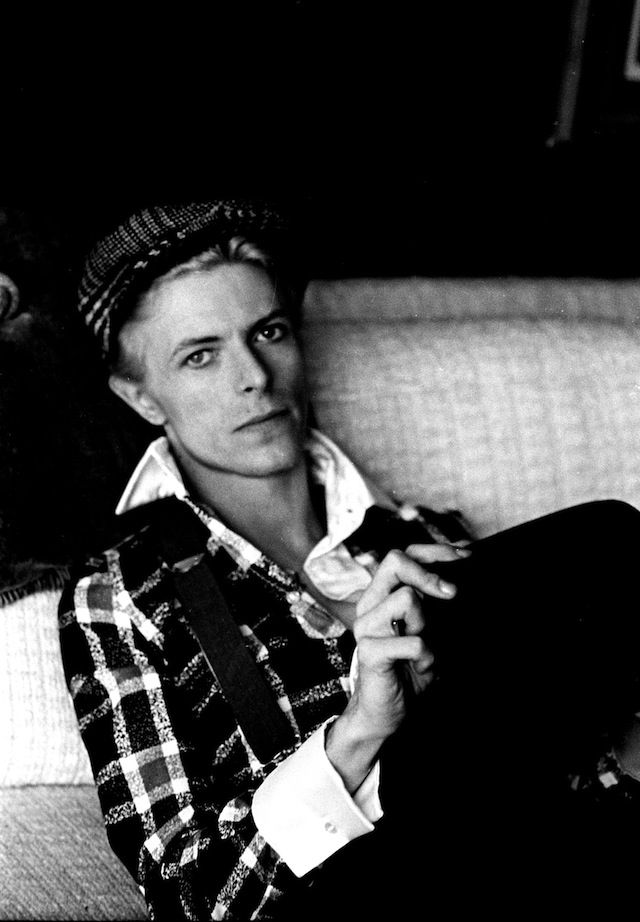

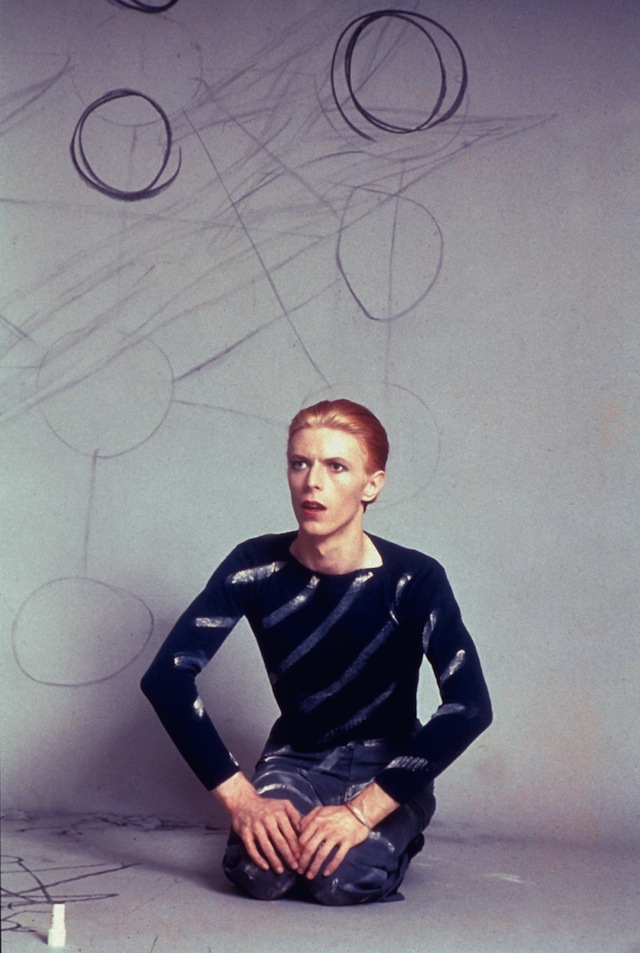

David out of character. One of my favorite photos of David. I particularly like his hands in this shot. Los Angeles 1975.

All photographs by Steve Schapiro, from Bowie, published by powerHouse Books.

Videos by VICE

In July 1973 David Bowie announced to a shocked London audience that that night’s show would be the very last for Ziggy Stardust, the character that had made him a superstar. Bowie would later write in his memoir that he had grown “exhausted and completely bored with the whole Ziggy concept.” With the release of Aladdin Sane the same year, Bowie strove to take a different direction, but his flamboyant new persona strongly resembled his last one. Something had to change, but the path forward wasn’t yet clear. For Bowie the year that followed was a period of immense transition.

By that time, the photographer Steve Schapiro had already established a reputation for capturing famous figures during crucial moments of transformation. Beginning his career as a political photojournalist, Schapiro photographed Martin Luther King Jr. at Selma and Bobby Kennedy on the ’68 campaign trail. In 1967 he shot Jerry Garcia, Janis Joplin, and Ravi Shankar in Haight-Ashbury. He was the set photographer for The Godfather; captured Cassius Clay the year before he scooped the world heavyweight championship and changed his name to Muhammad Ali; and when People magazine launched in ’74, Schapiro’s portrait of a pearl-necklace-biting Mia Farrow was its very first cover. Fascinated by his hero Henri Cartier-Bresson’s notion of “the decisive moment,” the perceptive photographer developed a knack for snapping it—both photographically and historically.

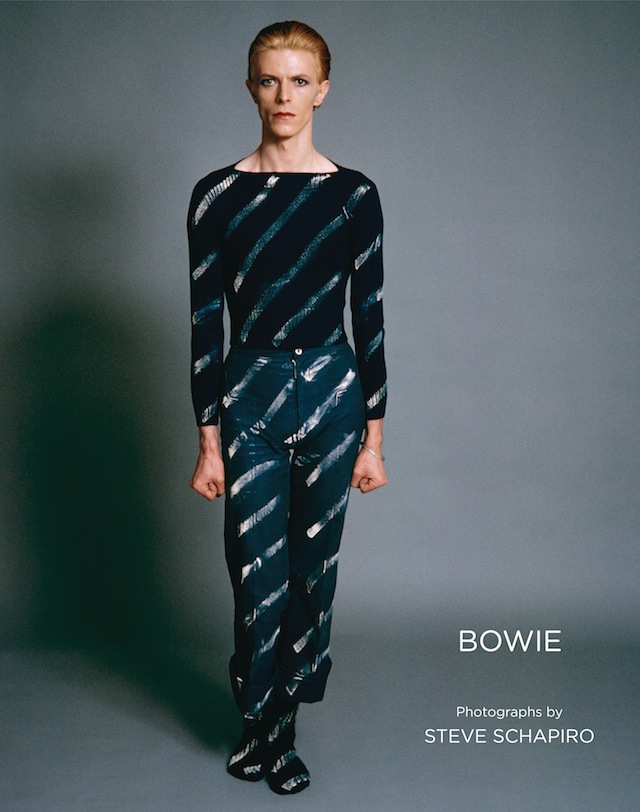

When Bowie’s manager, Michael Lippman, asked Schapiro if he’d shoot with the rock star, Schapiro agreed “before he could finish his sentence.” What followed was a 12-hour shoot in which several iconic photos of Bowie emerged, including the photo of Bowie in diagonal white pinstripes which he would reprise some 40 years later for his final video for “Lazarus.” Schapiro describes an easy rapport with Bowie, who took charge of the art direction himself—the idea to paint the pinstripes was all his—much to the delight of the photographer. Schapiro always prefers to be as quiet as possible on shoots to allow the personality of his subject to emerge. And on that day, it did.

At that time, the question of which Bowie you were going to get wasn’t to be taken for granted, but according to Schapiro, the one who greeted that afternoon was soft-spoken, relaxed, and polite, charmed to learn that the photographer had once shot Buster Keaton, one of Bowie’s heroes. Though the marathon shoot saw numerous costume and persona changes, what Schapiro witnessed was the constancy of the quiet, thoughtful man behind it all. Bowie “could appear as different people, like a chameleon,” Schapiro says, “but he was essentially himself.” This seamless duality was part of Bowie’s genius: he was both wholly his creations, and a man apart from them, and this is precisely what Schapiro captured that day.

Now, the photographs from the 1974 shoot, as well as dozens of others that Schapiro took of Bowie over the years—including the ones that would become the covers to Golden Years, Station to Station, and Low—have been collected in a coffee table book, simply called Bowie, due out this month. We talked Schapiro by phone at his home in Chicago to ask him about the experience of seeking, and finding, the man behind the legendary performer.

David relaxed at his house in Los Angeles, 1975. I particularly liked his hands in this photo.

Noisey: Did you know early in your career that you wanted to take photographs of great artists one day?

Steve Schapiro: I knew early that I wanted to do pictures which I felt in some way would last longer than a day or two. And the things I was interested in really ran the gamut. I was very interested in art at the time; I was interested in music. When I was an adolescent the biggest thing you could aspire to at the time was to work for Life magazine. So I did my own essays, I went to Arkansas and did a series on migrant workers, and I would bring it up to Life. There was a small magazine called Jubilee which would give you an eight-page portfolio, which was great. No money, which didn’t matter. It gave you a portfolio of pictures. I did a thing on narcotics addiction in East Harlem. Then Riverside Records hired me to do all their record sessions in ’61. So all of these were really the start, and each time was an attempt to—it’s always been an attempt—to do pictures which convey the spirit of a person or an event, or something of that sort. And my sense of it grew.

When I first started out, trying to emulate Cartier-Bresson, I would come back with contact sheets in which I’d missed the decisive moment, and they made no sense at all. But gradually I developed a sense of what I really wanted to photograph. My work generally is not stylish in the sense that Irving Penn is stylish. You look at one of his pictures, and you know exactly that it’s an Irving Penn photograph, and you also have a good sense of who he’s photographing. But in most of my pictures, I try very hard to get a sense of the person. I’m concerned about emotion, design, and information. And I feel all those things are relevant to a picture.

What was your perception of David Bowie before you met and how did that match up with what he turned out to be like?

Before I met him, he seemed to be a glamorous, incredibly talented, inventive rock ‘n’ roll performer who could transform himself into various people, seemed to go through changes. I feel that The Rolling Stones and the Beatles, they’re fantastic music, but their performances were very similar year after year. Even today The Rolling Stones in their performance, the way they perform is pretty much the way they’ve always performed. The backgrounds may have changed, and the songs change, but that aspect of things seems to be very stable. But Bowie seemed to have an enormous sense of growth. He would go from one thing to another, and as soon as he had really exhausted what he could do in one particular genre, or one particular persona, he would move on to something else. And kept growing. And I think that was true throughout his career. It’s brilliant when someone has that sense of growth, not only in terms of their music, but in terms of their whole personality, and the whole aura that they project.

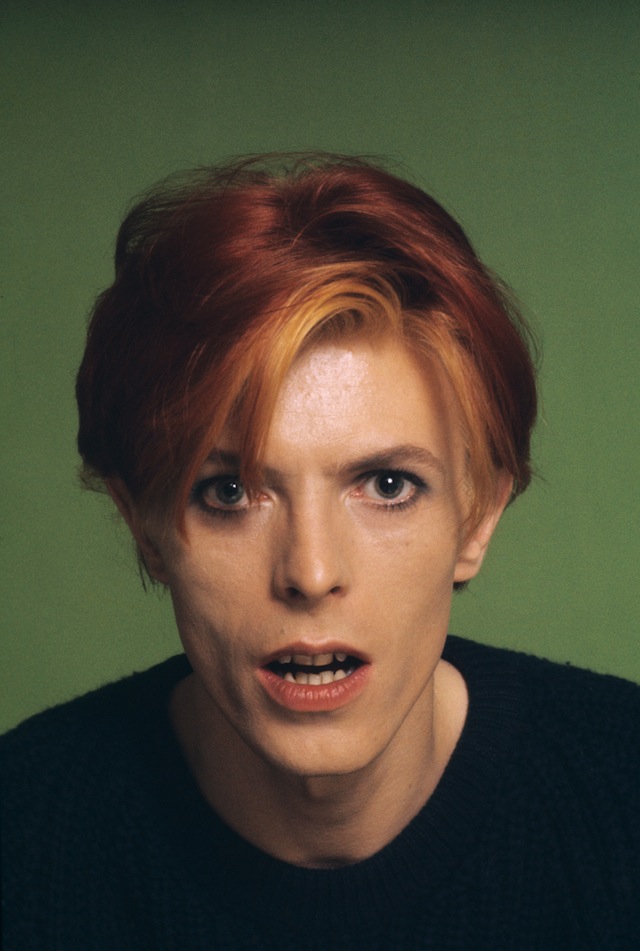

From the photo shoot for People Magazine. We took portraits against a putrid green background which we both felt was the worst possible color to use as a background for a magazine cover. Los Angeles, 1974.

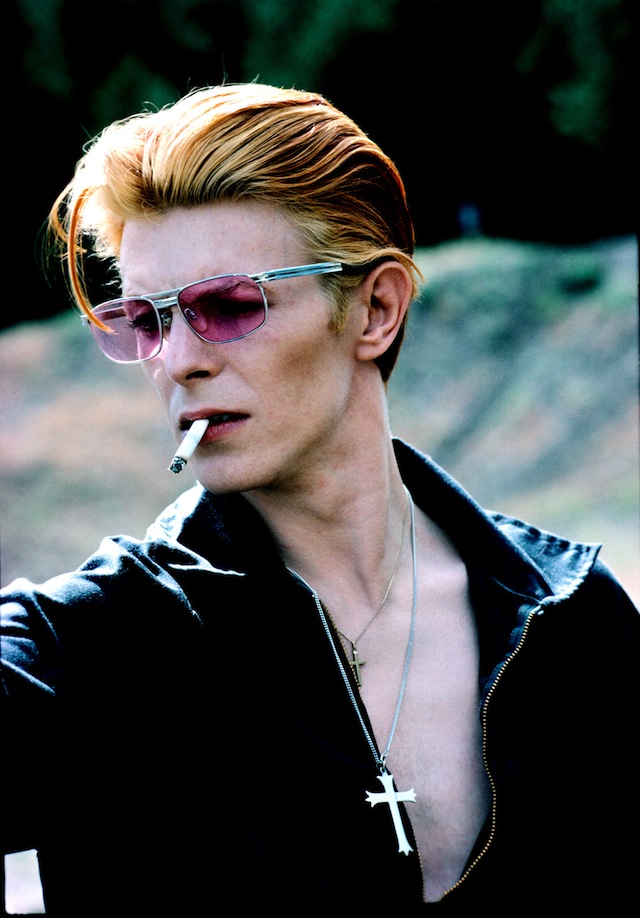

David with cigarette on a break from filming MFE in New Mexico 1975. This became a Rolling Stone cover and a popular image.

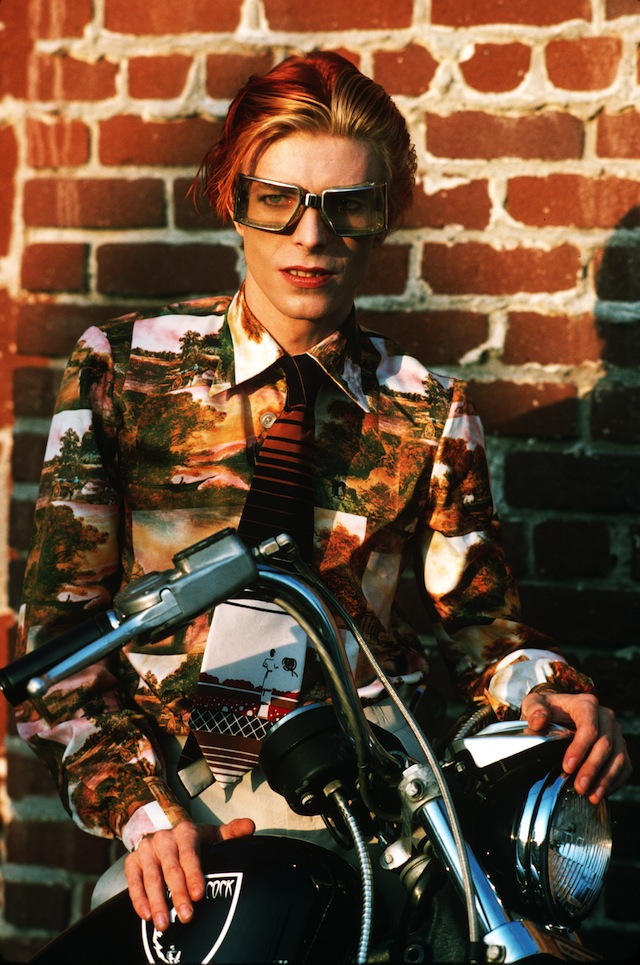

David with goggles and bike. Los Angeles, 1974.

It sounds like that spirit of continuous change was also how your first photo shoot went?

Oh, very much so. It started with, really, Bowie borrowing a shirt from one of my assistants, going in the dressing room, and painting himself these white stripes on everything, these diagonal white stripes, which again appear in the “Lazarus” video. And that’s the only two times they’ve appeared. So there was a very spiritual sense going on, and he started drawing these circles on the background paper, which was unusual for someone to do. At least no one had really done that with me before, and I had done a lot of lot of shoots. And then he drew on the background paper a diagram from the Kabbalah of the tree of life. And this was the first thing he did in terms of the shoot. So, basically, a lot of spirituality was on his mind at the start of this shoot. I had expected someone who probably was more rock ‘n’ roll oriented, and who also, in terms of what they wanted out of the shoot, would be more and more rock ‘n’ roll costume, that genre, or that that way of experimenting. And it seemed to me that he seemed to be showing more of himself in a lot of the pictures. Not all of them, but in a lot of them, where he’s not pretending to be a character. He’s being actually himself. That’s sometimes a rare thing in terms of the people I photograph.

I’ve photographed a lot of actors who develop a character internally and externally, and they are that character. And then when you put them in front of a camera, sometimes they don’t know who they are, and they’re very flabbergasted. They don’t know what expression to give you, because they’re very good at creating something, but in terms of who they are themselves, that isn’t as apparent to them at that moment when the camera starts clicking. It was very, very relaxed to work with him, and we seemed to be on the same frequency, which is an ideal way to work with someone. Sometimes you have to really work hard to get on that frequency and to get someone so relaxed that you can really get a sense of them in your pictures. The worst thing is when, in a shoot, someone’s talking to you all the time, because if they talk to you, they’re not being themselves. They’re more concerned in the conversation and with you. And that’s not what the pictures are after.

In addition to your photos of musicians and actors, you’re very well known for your photos of political figures. Many have said that Bowie, to them, had political significance in how he bent sexual norms and empowered people to be themselves. Did you see him as having a kind of political power?

Well, I saw him as someone who was very alert to the world, and certainly he created changes in the social world. I would say he was a person who had enormous confidence in himself. I’ve worked with a few other people who have had that. He had confidence that he was on the right track in terms of who he was as a person. I don’t know if that’s the right expression of it. But he had a strong sense of who he was, and a belief in that. You get some people who are talented and they’re very shy about bringing that out, because they’re not sure if their talent is real, or how people are going to appreciate them. Bowie just was a very awake person, awake to the world, and awake to, in his mind, how to make the world more open and better.

David seated drawing circles on the background paper and then the Kabbalah Tree of Life diagram on the floor. Los Angeles, 1974.

Do you have a favorite photo in the book?

I think there were a lot of pictures in the shoot which I’m really happy with. There’s a picture in the book which I call Bowie Blue, where there are these blue circles behind him. It was when they were shooting The Man Who Fell to Earth, and he has a glove to his face. I was doing a show last year in Chicago, at the Paschke Center, and the show was Andy Warhol, Velvet Underground, and David Bowie. We printed a lot of the David Bowie photos 30-by-40, 20-by-24, and I was happy with them. But when we looked at the show, I just felt, “I’m happy with the Bowie pictures, but they could be better.” And I went back to all of my transparencies for my shoots, and I found this transparency which had been totally overlooked all through the years. It’s from 1975, and it had never been printed, never been published, never been edited. So the night before the show, we made this 40-by-50 print of that picture, and it stole the show. It was everyone’s favorite image. So yes. There’s also a picture of Bowie holding the Buster Keaton book is a picture I like. It’s not necessarily iconic, but it’s a picture I like a lot.

Were you were you surprised when he reused the diagonal stripe outfit in the “Lazarus” video?

Totally surprised. Totally, totally surprised. It was nothing I would ever have expected. But what it did show to me was that the whole outfit, or the whole spiritual sense of, this strong sense of a Kabbalah, and all of that, that he had when we first started in ’74 was something that was very important to him, and that, spiritually, at the very end, it still was. I never expected to see that outfit again. And it’s an emotional thing to me, in the sense that, I felt even more of a closeness to him in a way and certainly an enormous sadness. A sadness which all of us felt.

Bowie is out today via powerHouse books.

Follow Joseph Staten on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

Image: Paramount Pictures -

Screenshot: Xbox Game Studios -

(Photo via Shawano County Sheriff’s Office)