Some people think that paleontology holds nothing but old news. As a paleo artist who draws dinosaurs and other ancient creatures for a living, I know that couldn’t be further from the truth.

Every year, new discoveries and research shake up old assumptions about life that existed on Earth long before us, and 2017 was no exception. The results, from the colour of dinosaurian feathers to soft tissue discoveries, are incredible. At the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, where I’m based, I use art to communicate the science of paleontology to captivate the minds of as many people as I can.

Videos by VICE

I’m happy to say that art is increasingly being considered essential for good science outreach, and here, I’d like to highlight some of the best art that graced new studies published this year.

Borealopelta markmitchelli by Julius Csotonyi

A few years ago, industry was doing what industry does out in Alberta, and that’s blasting through lots of rock to extract oil from the oilsands. In the process, the Suncor company uncovered a new species of nodosaur that, it could be argued, is the best dinosaur fossil ever found. This massive, heavily armored tank of a dinosaur was mummified and fossilized 110 million years ago, and what we have now is a near-perfect preservation of the front half of the animal, including soft tissues such as skin and keratin sheaths over the spikes and ossicles.

Because of this, Julius Csotonyi’s artwork of Borealopelta is probably the most accurate drawing of a nodosaur ever produced. From the arrangement of the scales, to the size of each spike, to the colours decorating the body, it’s all a reflection of reality.

Luskhan itilensis by Andrey Atuchin

Marine reptiles, such as this new pliosaur species, are especially strange due to the fact that their bodies take on very similar shapes to animals we are familiar with today, despite the fact that they haven’t swam the oceans in millions of years. The pressures of evolution to adapt to certain environments and certain prey availabilities results in convergent evolution, meaning that a certain body shape and function will be optimal to survive.

These pliosaurs were built for speed with a streamlined body and large, powerful paddles. They bear a striking resemblance to cetaceans, such as dolphins and whales. Andrey illustrates this new species to allude to this comparison, but gives it enough believable details to visually set it apart from the animals we know. Familiarity is a tool but also a dangerous temptation in paleo art, and I feel like this piece strikes the perfect balance between the familiar and the new.

Siamogale melilutra by Mauricio Anton

It’s never easy to choose a favourite Mauricio Anton piece, but it got a little easier after he illustrated a 100-pound, wolf-sized otter that prowled the wetlands of southwestern China, 6 million years ago. It had incredibly powerful and sturdy jaws, perfect for crushing hard prey like the shells of molluscs, but research is also suggesting that strong-jawed otters has less dexterity and tool-using capabilities. In other words, these giant otters may have been great with their jaws, but less proficient with their hands for smashing prey open. This beautifully painted scene shows a verdant and lush swampland full of life, where the giant otter is snacking on a mollusc.

Lemmysuchus obtusidens by Mark Witton

I couldn’t resist this piece for so many reasons. The fossils of Lemmysuchus were discovered in England, and sat misclassified for years in a museum. Once determined to be something new, this crocodylomorph from 164 million years ago deserved a name to match its own ferocity. In 2015, the world lost one of the hardest, heaviest pioneers of music to ever live, and he too hailed from England: Lemmy Kilmister, of Motörhead, whom this croc is named after.

This painting is what metal paleo art dreams are made of. The atmosphere is dark and foreboding, in a wetland smattered with decay. In the moonlight, a monster devours the flesh of prey. Poor little fish. You could say it was “Killed by Death” himself.

Anchiornis huxleyi by Rebecca Gelernter

Anchiornis huxleyi, did you get a new ‘do? Because I think it’s adorable. Paleontologists have been adding pieces to the puzzle of Anchiornis for quite some time. Several years ago they successfully identified the colours of its wing feathers, and now they’ve discovered a new type of contour feather that would have covered most of its body.

The contour feathers of modern birds are round and flat, making them smooth, aerodynamic, and water-repellent. But these are V-shaped, with only a few simple unconnected filaments on each side. This results in a very fluffy and soft little flying dinosaur. Rebecca Gelernter did a lovely job illustrating this new depiction of Anchiornis in an Audubon style, as if you might find this in an identification guide for your next paravian-watching trip.

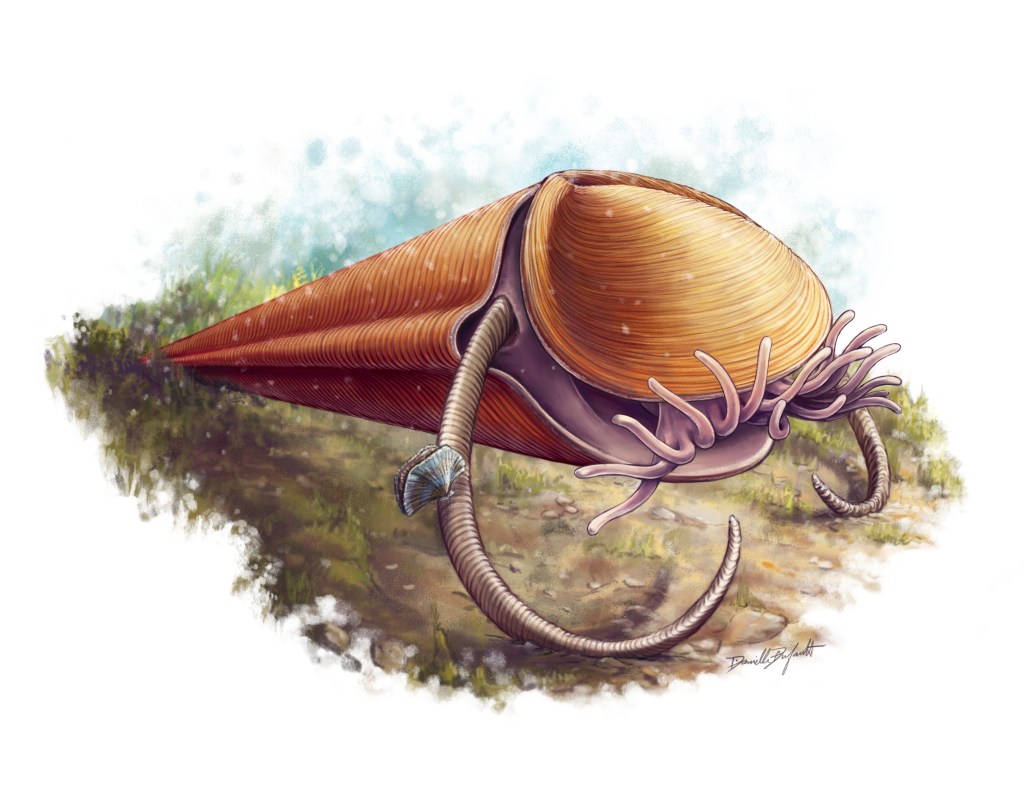

Lagenanectes richterae by Joschua Knuppe

A new elasmosaurid from early Cretaceous Germany was published this year, and the art evokes all of the fear in me that an ocean full of gigantic, toothsome swimming reptiles should. The scariest part is how realistic and believable the scene is. Night time in the ocean really should make you feel this small and insignificant in the face of these beautiful, svelte, but wicked-grinned animals.

Read More: Mud Dragons, Tully Monsters, And Toothed Whales: The Best Paleo Art of 2016

Their wide jaws were specially adapted, with long teeth that spread sideways and outwards rather than perpendicularly. The use of light is clever and believable, capturing a dimly illuminated scene that lets us glimpse at these gargantuan shapes (about 8 meters long!). The school of fish and silvery squid glinting in the light add real beauty to balance the frightful forms of the giant reptiles.

Vouivria damparisensis by Chase Stone

This is perhaps my favourite depiction of a sauropod that I have ever laid eyes on. Featured here is the oldest known brachiosaurid dinosaur, hailing from Jurassic France.

You see, the best and worst thing about sauropods is that they are so incredibly large and long, that to capture their entire bodies in the frame of an image, you need to set the view incredibly far back from the animal, creating all kinds of strange distortion to proportions. This is different altogether: instead of viewing at ground level, we’re at Vouivria-level, giving us a vantage point that is quite fresh and surprising! From the lighting to the sensible-yet-striking colouration of the animals, there’s nothing I don’t love about this piece. It is extreme perspective done right.

Wakaleo schouteni by Peter Schouten

The end of 2017 seemed to come packed with incredible new taxa adorned with great art, and several made the cut. Wakaleo schouteni is depicted here, and the authors of the paper honoured the artist with the name. It’s a thylacoleonid, or marsupial lion from the Late Oligocene-middle Miocene, predecessor of the famed Thylacoleo carnifex.

It’s truly hard to stop looking at this painting. I can’t help but appreciate every single brushstroke that went into this work. He’s a real master of colour and texture, and every little tuft of fur makes me want to reach out and touch it. I find myself utterly convinced that this animal still exists!

Halszkaraptor escuilliei by Lukas Panzarin

Another great reveal, coming right at the end of the year, presented us a new and very strange dromaeosaurid. This turkey-sized Mongolian dinosaur from about 75 million years ago had an elongated neck, reduced forelimbs that may have helped it swim, a slim and short snout, and a mouth full of small sharp teeth. Scientists propose that it could have been semi-aquatic, much like fowl or cormorants. The reconstruction of this newly discovered dinosaur is beautiful and striking, and I admire the treatment of the white feathers. It drives home the “swan-like” appearance of the animal. Technically, the white feathers are expertly done, looking more like prisms catching all the colours of the rainbow. Colour theory and light refraction at its best!

Zuul crurivastator by Danielle Dufault

Hopefully, it’s not too offensive to include a bit of my own work. Zuul crurivastator, a new species of ankylosaurid from the late Cretaceous of Montana, has been near and dear to my heart for the past year, as it has been the subject of research in our lab at the Royal Ontario Museum. The tail and skull were the first parts prepared and published on, but there’s much more of the animal to come, and many more interesting studies to be done.

This six-meter behemoth was named for its close likeness to Zuul, a dog-demon from the Ghostbusters movie. The specimen’s preservation is exceptional, including soft tissues like skin, ossicles, and keratin sheaths on the osteoderms. It was a pleasure to reconstruct and bring to life, and I hoped to make it vibrant and striking. We don’t know what colour it truly could have been, but I can’t rule out that we may be able to find some of that out in time. I’m eager for the day.

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter .