Listen to the VICE News podcast “Chapo: Kingpin on Trial” for free on Spotify.

CHICAGO — From the time he was a boy, Vicente Zambada was groomed to be the future leader of the Sinaloa cartel. The eldest son of Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, Mexico’s most powerful drug trafficking organization was his by birthright. He followed in his father’s footsteps for years, becoming his top lieutenant and emissary. But it was ultimately his ill-fated attempt to quit the cartel that landed him in a U.S. federal courthouse Thursday.

Videos by VICE

With a tousle of dark hair, a fresh shave, and a gray suit with a pink tie, the 44-year-old Zambada swaggered into the courtroom of Judge Ruben Castillo like a man accustomed to getting his way. He pleaded guilty in 2013 to smuggling cocaine and heroin, but his sentencing was repeatedly delayed as U.S. authorities pumped him for information and used his testimony to put away several of Mexico’s most notorious narcos, including his father’s longtime partner, Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán.

Citing his “extraordinary and unprecedented” cooperation, prosecutors in Chicago recommended a 17-year sentence for Zambada rather than the maximum of life in prison. Amanda Liskamm, a prosecutor who worked the Chapo case and questioned Zambada when he was on the witness stand, praised his “positive attitude” and said he’d “provided the jury with a unique perspective into the inner workings of the cartel.” She said a reduced sentence for Zambada was needed in order to “incentivize other criminals out there who engage in serious drug trafficking who are thinking about engaging with the government.”

Judge Castillo went even further, reducing Zambada’s sentence to 15 years. With credit for time he has already served in the U.S. and Mexico, Zambada could be allowed to walk free in five — or less, with good behavior.

As Zambada stood before him, swaying gently on his feet, Castillo spoke at length about his sentencing decision. He noted that Zambada was perhaps the highest-level drug trafficker who’d ever appeared in his court, but his case still made no dent in the flow of drugs to the U.S.

“His sins are washed away merely because he testified. The government buys testimony in exchange for reduced sentences.”

“After 25 years of being a federal judge, if there is a so-called drug war, we are losing,” Castillo said. “It’s time for us to think about doing something different.”

Castillo noted that he is of Mexican descent and lamented the high death toll from the drug war in Mexico, which he called “the only crisis at the border.” He also used the occasion to lambast President Donald Trump, though he referred to him as “someone in D.C.… I don’t want to say his name.”

The judge also criticized Trump for speaking out against cooperators (in a Fox & Friends interview last August, he said it should be illegal for investigators to offer leniency for cooperating witnesses). “Are you kidding me?” Castillo said. “They are cooperating with the Justice Department.”

Zambada was far from the only former high-level drug trafficker called to testify against Chapo, who was convicted Feb. 12 after a dramatic three-month trial in Brooklyn. Chapo now faces life in prison, though he is seeking a new trial. Thirteen other cooperators took the stand, including Zambada’s uncle Jesus “El Rey” Zambada. All of them sought leniency in their own cases, but the younger Zambada — known as “El Vicentillo” — is the first to find out exactly how much prosecutors were willing to give up in order to convict Chapo. The answer, it seems, is quite a lot.

Read more: The brother of Chapo’s partner just spilled the Sinaloa cartel’s secrets.

In addition to his relatively short sentence, Zambada disclosed during his testimony against Chapo that U.S. authorities had already arranged to bring his wife and children across the border and provide security for them. He is expected to receive a rare S-visa, which puts foreign-born cooperators in major criminal investigations on the path to a green card and U.S. citizenship. The Treasury Department also agreed to lift sanctions on Zambada’s wife, who was allowed to bring $400,000 with her to the U.S. for living expenses. Under the terms of his plea, Zamabada agreed to forfeit his illicit drug proceeds — which prosecutors say are a whopping $1.37 billion, but it’s unclear when — if ever — he will be forced to pay up.

Chapo’s former attorney, Eduardo Balarezo, who cross-examined Zambada during the trial, called his sentence and other benefits “a prime example of the corrupt nature of the federal criminal justice system.”

“Vicente Zambada admitted to being responsible for trafficking hundreds of tons of drugs to the United States,” Balarezo said. “Yet his sins are washed away merely because he testified. The government buys testimony in exchange for reduced sentences.”

Read more: A juror speaks for first time about convicting Chapo.

In a sentencing memo filed earlier this month, federal prosecutors told Castillo that Zambada was a reluctant participant in the cartel who tried to do the right thing by cooperating. Prosecutors said Zambada “shied away from involvement” in the drug business,” and only got involved “as a result of the unavailability of his father.” Because his dad was in hiding, prosecutors said, cartel members constantly asked Zambada to relay messages to him.

Zambada himself offered a similar story during Chapo’s trial, but said the turning point came in the early ‘90s when a war broke out between the Sinaloa cartel and their rivals in Tijuana. Zambada was called to his father’s side for safety reasons, and he learned how to run the cartel by watching him operate. “I started realizing how everything was done,” he said. “And little by little, I started getting involved in my father’s business.”

The 71-year-old El Mayo has been a legend in the Mexican drug trade for more than three decades. While other major traffickers have been killed or captured over the years, Mayo has remained free for his entire criminal career. With Chapo now out of the picture, Mayo has reportedly consolidated power and now leads the cartel from his remote hideouts in the mountains of Sinaloa. The U.S. State Department is currently offering a $5 million reward for information that leads to his arrest.

Before long, Mayo’s heir apparent was coordinating multi-ton cocaine shipments from Colombia and overseeing a team of assassins. The younger Zamabda maintains he never personally killed anyone, but he acknowledged during Chapo’s trial there were “several times” when people were kidnapped, tortured, and killed on his orders.

After Zambada was indicted in the U.S. on drug charges, he tried to find a way out that didn’t involve death or life in prison. “I wanted to get out of the cartel,” he recalled. “I wanted to retire from everything with my dad and with my Compadre Chapo’s permission.”

In March of 2009, with the blessing of both his father and Chapo, Zambada met with DEA agents at a hotel in Mexico City to discuss leaving the cartel and becoming an informant. Such an arrangement was not unprecedented. Since around 2005, DEA agents had been secretly meeting with a Sinaloa lawyer named Humberto Loya-Castro. He was an adviser to Chapo, and he was feeding the DEA information about rival groups. Loya-Castro’s own federal indictment disappeared in 2008 as a result of his cooperation. Zambada wanted the same deal.

Loya-Castro was present during the meeting between Zambada and the DEA, but the plan for the cartel scion to become a snitch was derailed a few hours after the rendezvous, when Zambada was arrested by Mexican special forces. He was extradited in 2010 and agreed to become an informant in late 2011, after spending nearly two years in solitary confinement at a federal jail in downtown Chicago.

Prior to his cooperation, Zambada claimed in a 2011 court filing that he could not be prosecuted because the DEA had given Chapo and Mayo “carte blanche” to smuggle drugs into the U.S. in exchange for providing tips that helped Mexican and U.S. authorities “capture or kill thousands of rival cartel members.” The Justice Department has acknowledged that the meeting with Loya-Castro and Zambada occurred, but it has steadfastly denied that Zambada was ever promised immunity.

Read more: Prosecutors don’t want El Chapo’s jury to hear how the government sent drugs to the Sinaloa cartel.

During the Chapo trial, attorneys were under court orders not to mention Zambada’s past claims about having permission from U.S. authorities to traffic drugs. It was mentioned briefly, when Zambada described his plan to “retire from everything with my dad and with my Compadre Chapo’s permission,” but ultimately Zambada’s testimony was focused on Chapo, who is the godfather to Zambada’s youngest child.

Zambada worked closely with Chapo and was privy to the cartel’s deepest secrets, and he did not hold back on the witness stand, detailing how Mayo and Chapo organized massive drug shipments, murdered rival traffickers, and doled out more than $1 million in bribes per month to corrupt Mexican politicians, police commanders, and military generals.

Zambada’s attorney, Frank Perez, told the judge that the decision to testify against Chapo was not easy for his client.

“He struggled with that,” Perez said. “He did not want to testify. He was concerned about the consequences he would suffer, and not just him but his friends and family.”

“This feeling of repentance has been with me for years.”

When it was Zambada’s turn to speak Thursday, he addressed the court in Spanish and began by “asking all those people for forgiveness who I hurt one way or another, either directly or indirectly.”

Zambada said he had made “some bad decisions” in his life, “which I truly regret.” He added that he felt he “can be a better father, a better husband, a better son, and most of all a better human being.”

“I would like to tell your honor this repentance did not just come about just yesterday nor did it come about just because I’m in front of you about to receive a sentence,” Zambada said. “This feeling of repentance has been with me for years.”

In addition to Chapo, Zambada dished on the leaders of the Beltrán-Leyva Organization and Damaso Lopez, a former right-hand man for El Chapo who is now serving life in U.S. federal prison. Also known as “El Licenciado,” Lopez was among those who testified against Chapo during his trial.

Federal prosecutors say Zambada is “one of the most well-known cooperating witnesses in the world and he and his family will live the rest of their lives in danger of being killed in retribution.”

“If there is a so-called drug war, we are losing.”

Even with Chapo behind bars, little seems to have changed in Chicago or elsewhere in the U.S. Chapo was named “Public Enemy No. 1” in 2013 because he was blamed for supplying drugs that fueled gun violence in Chicago, but the impact of his capture and conviction is negligible at best. Shootings are down about 12 percent across Chicago so far this year, according to police, but Cobe Williams, deputy director of the Cure Violence program the University of Illinois in Chicago, said the positive trend is not linked to Chapo or Zambada.

“El Chapo and this other guy ain’t got nothing to do with what’s going on in Chicago,” said Williams said. “None of this got nothing to do with what’s going on in Chicago.”

A native of the gang-plagued Englewood neighborhood on the South Side, Williams said the decline in shootings was the result of work by groups like his, which seeks to intervene in neighborhood disputes before such conflicts escalate to violence.

“A lot of things that drive the violence is personal,” Williams said. “People have a personal altercations or beefs. It ain’t no gang relationship. People get that twisted. It’s personal.”

Meanwhile, the DEA has moved on to target other groups that traffic drugs to Chicago. While Mexico’s new president has floated some radical new ideas to reduce drug violence, the status quo remains the same. Drugs continue to flow across the U.S.-Mexico border. El Chapo is gone, but his sons now run his faction of the cartel. Another one of Mayo’s sons, Serafín Zambada, was released from U.S custody last September after striking a plea deal that allowed him to serve less than six years in prison. Mayo has at least two other sons still in Mexico, including one awaiting extradition to the U.S. and another who is still on the run.

Castillo seemed to recognize the futility of the situation during Zambada’s sentencing.

“We need to discuss demand and fund treatment,” he said. “If you don’t address the demand, there will be plenty of people to fill the role of sending drugs to this country.”

This article has been updated to correct the spelling of Amanda Liskamm’s last name.

Cover: In this March 19, 2009 file photo, drug trafficker Jesus Vicente Zambada Niebla is presented to the media after his arrest in Mexico City. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo, File)

More

From VICE

-

Images via FBI -

A DEA agent (Photo by RJ Sangosti/MediaNews Group/The Denver Post via Getty Images) -

Photo by MANDEL NGAN / AFP. -

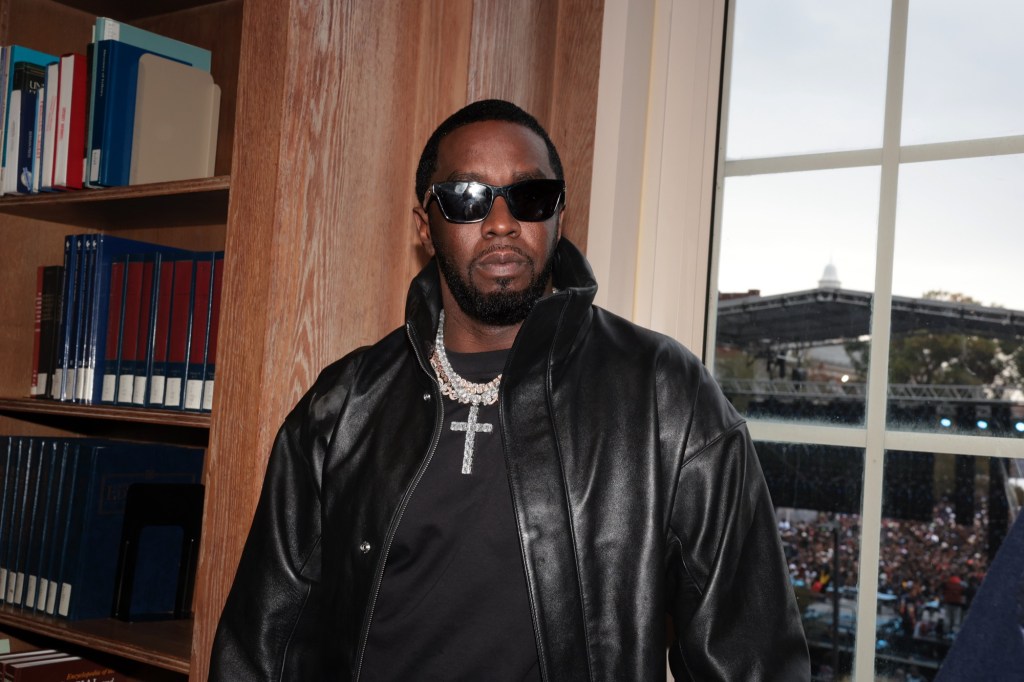

(Photo by Shareif Ziyadat/Getty Images for Sean "Diddy" Combs)