A little over 50 years ago, it was not only unheard of to see a woman participate in an official marathon. Doctors and medical practitioners saw the act of women running for sport as flat out life altering—believing such extreme fallacies that if women ran such distances they would grow a masculine, muscular body and that their uteri would fall out.

It was a belief that frustrated a then 20-year-old Kathrine Switzer, and what eventually encouraged her to participate in the 1967 Boston Marathon. A journalist in training while attending Syracuse University, Switzer signed up for the race under her gender-neutral writing pseudonym, K.V. Switzer, in order to assure that no one would question her participation.

Videos by VICE

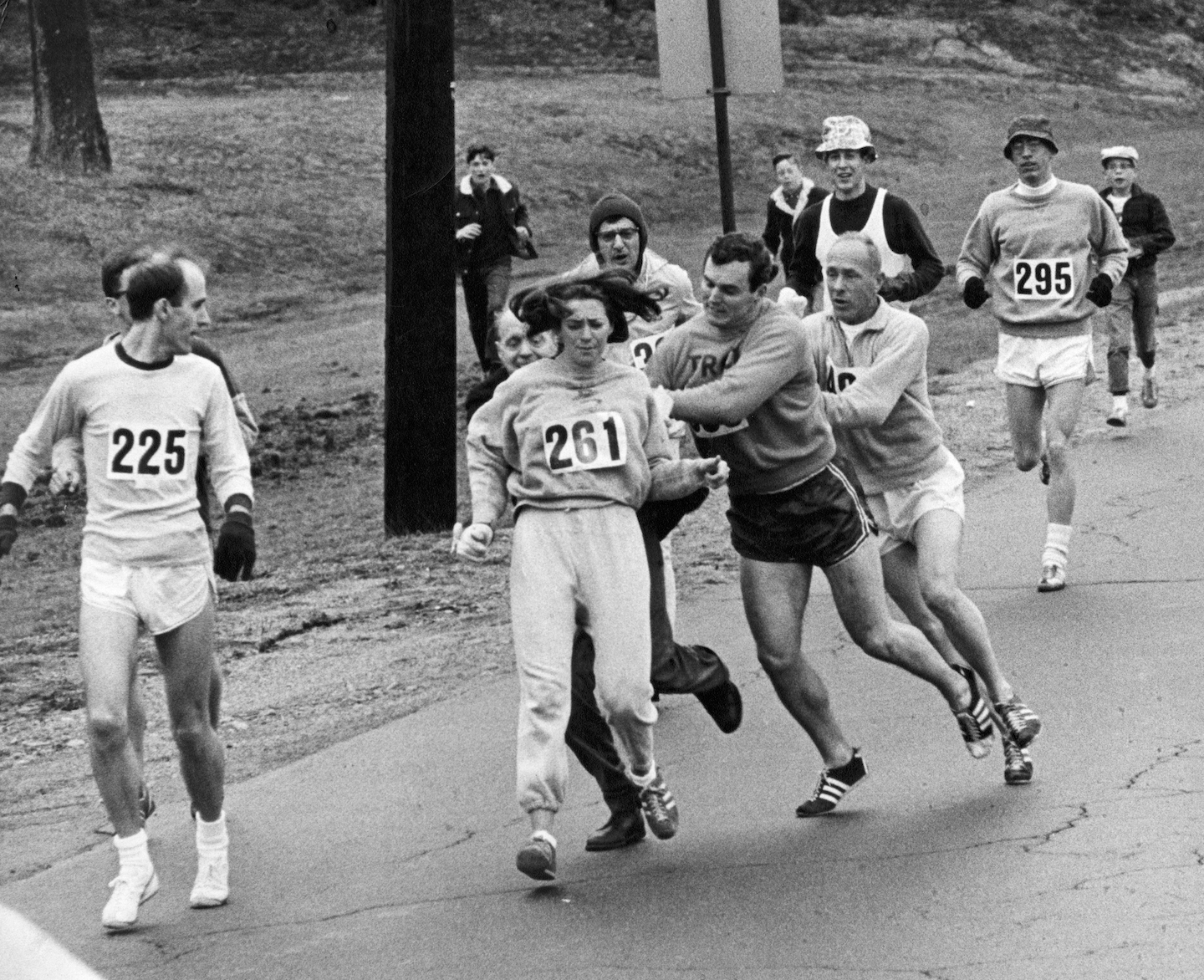

The rest is quite literally history and documented in what are now considered iconic photographs that physically dictate the beyond unbalanced gender dynamics of the late 60s. A racing officiant is seen attempting to grab Switzer from behind and rip off her participant bib when it becomes evident that Switzer was indeed a woman. Simultaneously, Switzer’s boyfriend, also participating in the marathon, shoves the man to the ground in order for Switzer to keep running.

In an excerpt from her memoir, Marathon Woman, Switzer had no understanding of what her entering the marathon would quickly become.

“I had no idea I was going to become part of that history,” she recalled. “I wasn’t running Boston to prove anything; I was just a kid who wanted to run her first marathon.”

The disbelief surrounding Switzer’s willing involvement in the marathon alongside the belief that women could not and should not run all circled back to the cultural climate of the 60s, where misogynistic viewpoints still ruled and decided what was “best” for women at the time.

“The medical and athletic establishment was so horrified at women in general and Katherine Switzer in particular because in the 1960s they still subscribed to long standing beliefs that women were constitutionally unfit to do strenuous exercise,” Natalia Mehlman Petrzela, a historian, professor at The New School and host of the Past Present Podcast tells Broadly.

“The medical [community] worry was that intense exercise — like distance running or heavy lifting — would compromise women’s fertility. But these ideas gained even more traction because they fit in with cultural concerns. Advocates for women’s exercise contended with the assumption that sports would cultivate both a muscular body and competitive spirit, both of which were thought to be undesirably masculine traits.”

Barring women from participating in marathons and running in general, was very much a patriarchal-based decision. Those who created the rules and guidelines centered around sports and who could and couldn’t participate were very much mirrored by cultural norms at the time.

“It’s important to realize that women have not been excluded from all sports in equal measure,” Mehlman Petrzela adds. “Distance running because of its intensity but also because women competing in an individual sport on the open road, was perceived as particularly off-limits to women. But as early as the 19th century, golf, group dance, lawn tennis, and calisthenics were all considered appropriate [activities for women].”

Switzer wasn’t the first woman to run in a marathon unofficially—Roberta Gibb ran before her the year before, but joined the marathon unofficially, rather than signing up and concealing her gender. Switzer’s more sly participation—although not necessarily illegal since there was no specific written legislation that stated women could not enter the Boston Marathon—was a needed tipping point that showcased women could not only participate in highly-strenuous sports, but they could also excel at them as well.

Women weren’t officially allowed to participate in the Boston Marathon until 1972. Women weren’t allowed to run more than 1,500 meter length races before, leaving marathon participation strictly meant for men, but in the decades since then, have joined in on the sport of long distance running in droves.. According to a 2013 report by Running USA, women participation in marathons increased from a mere 11% in 1980 to a staggering 42% by 2012.

For More Stories Like This, Sign Up for Our Newsletter

In a 2007 essay Switzer wrote for the New York Times, reminiscing on her Boston Marathon moment, she described the swift attraction of women towards marathon running as “help[ing] transform views of women’s physical ability and help redefine their economic roles” as well as “empower[ing] women and [raising] their self-esteem while promoting physical fitness easily and inexpensively.”

In the moments leading up to Switzer’s legendary first run, her mindset was on solely that — being able to run and run on her own terms. But as the countless press, interviews, and recognition that followed her from that finish line to today, Switzer’s participation was an unknowing moment of activism that paved the way not only for runners to come, but women’s eagerness to show off their strength unabashedly, in all sports across.

“Women won the right to run it, and they do so powerfully, inspiring others,” Switzer continued in her essay. “In 40 years, female marathoners [went] from being labeled as intruders to being hailed as stars of the sport.”