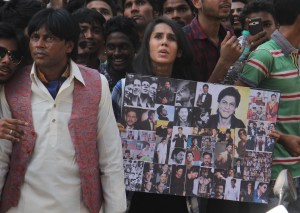

Lately, the only thing more ubiquitous than Shah Rukh Khan himself are clips of people watching Shah Rukh Khan. His latest film Pathaan, while far from flawless, has become the highest-grossing film of his career. It has scripted a triumphant comeback for the 57-year-old actor who is seen flashing his chiselled abs in the film with the swag of a seasoned superstar.

The sheer ecstasy of watching King Khan on the big screen again is palpable. It’s the sort of feverish, explosive reaction that hasn’t gone his way in a while – to my mind, at least – since Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (DDLJ). The 1995 film struck a chord with people of all age groups across the country and abroad. Including me. At age 9, I may not have been able to fully comprehend the storyline or subtext, but that experience of watching it in a single-screen theatre in Ludhiana in northern India stayed with me.

Videos by VICE

Some young adults today, though, cannot fathom the fandom that movie elicited. “I watched DDLJ recently, and cringed,” said 22-year-old Ragini Maheshwari. Hailing from Dehradun and working in Bengaluru at a digital media agency, Maheshwari is aware of the reviews and craze around Pathaan, but doesn’t think it is worth the hype or money. “I’m not a fan myself, but I know people who are. They usually qualify it by saying they are fans of his work in the 2000s when he was in his softboi era.”

Is Maheshwari’s cool, aloof reaction to the “last of the superstars” simply because she wasn’t born when DDLJ was released in 1995 and doesn’t have the necessary context? Or is it symptomatic of a larger change in the very nature of fandom and, by extension, superstardom itself?

Curious about how Gen Z is reacting to this moment, I took the question to Reddit. On r/bollywood, I receive hundreds of responses, many of them screaming adoration in all caps, detailing exactly when their one-sided infatuation began. Several say they can’t relate to him, and would rather watch Bollywood superstars Shahid Kapoor and Hrithik Roshan. A few point out that SRK is still the most likeable of the Khans. Others find him unbearable, and still others sagely point out that it is actually the generation after Gen Z that will not be able to relate to him.

“Khan has an enduring star power that includes the younger generation,” said Ranjani Mazumdar, professor of Cinema Studies at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, JNU. Mazumdar, who has watched Pathaan twice in ten days, sent me a clip of the audience grooving to the title track “Jhoome Jo Pathaan” in a single-screen theatre in Delhi. “It is always difficult to predict why a film works with large audiences. This is a film with a utopian promise that seeks inclusivity and is also cosmopolitan.” In this case, felt Mazumdar, star power fused with the actor’s biography, and woven into the narrative, may have all done the trick.

As I wonder if Shah Rukh Khan’s fandom isn’t as monolithic as it once seemed to be, there he is, on Twitter, busy with yet another one of his daily AMAs – batting proposals and amusing his 43 million followers with his dad jokes. “He is aware of generational shifts and is working towards that. But age is hardly something we can defy forever, so obviously new icons will emerge,” Mazumdar added.

There has been a visible shift in who can achieve icon status now, and where they come from – which seems to be absolutely anywhere. In this evolving matrix, as reach and access has grown, more qualitative aspects to fandom such as accountability and authenticity, have emerged. Like with everything else in 2023, the Internet has a lot to do with it.

Fandom for India’s Boomers and Gen X was defined by language and geography, for the most part. Until 1991, pre-liberalisation India had one TV channel (Doordarshan) and radio broadcaster (AIR) each – not to forget that the hardware was scarce, and there was a limited number of single-screen theatres. Only a handful of artists reached that rarefied position right at the top. Even if Amitabh Bachchan and the late actor MGR, for example, had international fandoms, they were confined to a subgroup that spoke Hindi or Tamil. Kapil Dev was widely revered, but only in those places where cricket was a part of the sporting culture.

In 1991, private cable TV came along with five Star channels. India’s first multiplex, PVR Anupam, opened in Delhi in 1997 (with SRK’s Yes Boss as one of four films on screens). The first dial-up internet connections were offered by VSNL in 1995. In 2001, the first private radio station, Radio City, came on air in Bengaluru. By the time I turned 18 in 2004, the wall behind my computer (assembled in Nehru Place, Delhi), was covered with posters of Tom Cruise, Rahul Dravid, Backstreet Boys, Saif Ali Khan and Destiny’s Child.

In the last decade, with smartphones, social media and streaming, our screens have shrunk into tiny personal theatres that fit into the palms of our hands, complete with Dolby digital sound and subtitles in the language of our choice. And our world has expanded exponentially. What’s interesting is the effect this has had on fandoms, which are now “personalised” in a sense – both more niche and colossal, at once more splintered and cohesive than ever before.

Naturally, as we easily become “followers” of individuals who we resonate with, stardom (primarily a factor of numbers) is also in flux. Today, Kannada actor Yash has a national following; Telugu filmmaker SS Rajamouli has minted a global one. Rakhi Sawant has multiple, very loyal fan clubs on Instagram, where I also found five for the actor Cwaayal Singh, who debuted in the Netflix series Class a week ago. And who can forget Netflix’s year of Radhika Apte in 2016, transforming the actor into a star overnight?

The first official Bangtan India fanclub – the BTS Army – started a decade ago, with 126K followers today – and it’s just one of dozens, populated by teens who have, on occasion, needed to be hospitalised to combat the intensity of their obsession. Taylor Swift fans hold regular Swiftie Nights across India to celebrate their queen.

“That’s amazing, right: All the way here, where she doesn’t deign to come?” said Fawzia, a Swiftie and “zillennial” (on the cusp of millennial and Gen Z) living in Gurgaon. Her own love for Swift, reborn when the album 1989 arrived in 2014, is restricted to participating in a Swiftie subReddit, and writing articles for pop culture sites. “I like listening to words and she’s such an amazing lyricist. I naturally relate more to the universality of complex emotions in her music over a rapper talking about cars and girls.”

That she has been vocal about her politics – anti-Trump and pro-LGBTQIA – has added to Swift’s appeal. “Plus, she develops this really intimate connection with her fans with her Swiftmas (where she has handpicked fans off social media and delivered personalised Christmas presents) and secret private listening sessions of new work before it is released publicly.”

Parth Rahatekar, 24, also identifies as a “massive Swiftie.” “Maybe it’s because I think in English, maybe that’s just the media landscape I live in,” Rahatekar said about why they don’t resonate with musicians closer to home as much. “But I do love Salman Toor’s work,” they added, referring to the New York-based artist from Lahore. “Whenever he drops new art, I reorganise my whole life around it.”

Shikha Chandrashekhar feels similarly about American rock band All Time Low. “I’ve been listening to them since I was 13,” said the 24-year-old from Bhopal who works as a copywriter in Bangalore, and is the lead vocalist in her band Akog. “They’ve largely influenced my sound as a musician. Their music has changed over the years, it’s become more commercial, but I’d defend them to the death.”

Geographical and cultural proximity might not be an obstacle for artists and celebrities to connect with fans but what appears to matter more (after their art, of course) is their values. Authenticity – perceived authenticity at any rate – is chief among them.

“I love Arijit Singh, he’s had a huge impact on me as a person and musician,” says Dushyant Shingare, a 22-year-old dentistry student who hails from the city of Wardha in Maharashtra, India. “It’s just the kind of man he is; how simple a life he lives despite having everything. I admire that cool and simple approach.”

Yogesh M, a 22 year-old software developer and skateboarder from Bangalore, started watching the late Kannada actor Dr Puneeth Rajakumar’s work in his childhood. “His films were mostly family-oriented, and he always came across as a very genuine, warm person. When I was in 12th grade – it was his birthday on the last day of our final exams – I made badges and distributed them. This year, I’m planning to run a marathon dedicated to him.” Others that he looks up to include Chester Bennington of American rock band Linkin Park, skateboarders Kima from Mizoram and Jakkss from Mumbai.

Vast or hyper-niche, it’s no secret that fandoms are more powerful now than ever before. One need only look at the presenter lineup at the final award at the Grammys 2023 ceremony: 10 superfans on stage with Trevor Noah to give away the Best Album Award. No doubt, these are still parasocial relationships; but now they are interactive ones as well, not as static and one-way as they used to be. This unprecedented exposure that we have to celebrities feeds into their stardom – but, ironically, chews into it as well.

“I used to think Cristiano Ronaldo is the GOAT,” said Maheshwari. “But when I became aware of all the sexual assault cases against him, and that no one calls him out for it, that became a lens: To see that he’s great at football, but he’s also done wrong things in his life. I’m always going to try to have that objective lens. I don’t think I’d ever put people on a pedestal.”

Fawzia feels her Swiftie-ness waning, especially after the Ticketmaster debacle – Swifties have sued the American company in charge of selling tickets for Swift’s upcoming Eras tour, due to blunders like astronomical pricing and the website crashing. The company is now being investigated by the U.S. Congress. And while Swift has criticised the company as well, fans like Fawzia feel she could’ve done more.

Chandrashekhar stopped being a fan of Hindi film actor Ranbir Kapoor when she realised he sorely lacked versatility. A year after the slap, American actor Will Smith is still struggling to regain composure. Author JK Rowling’s transphobic comments from two years ago had diehard fans (like me) unsubscribing, and continue to impact her empire today – most recently, in the controversy surrounding the new video game Hogwarts Legacy.

On the other hand, there are celebrities who just can’t connect. Rahatekar finds Bollywood personalities, with their highly curated Instagram feeds, particularly remiss. “I feel like there’s a lack of vulnerability,” they said. “I usually can’t tell the new lot apart. They’re so cold and unrelatable; it’s all too curated. Where are the messy stars? Where’s Preity Zinta saying [allegedly], “Aaj ki Sweetu, kal ki Me Too”? People were obviously, rightfully angry at her, but there were also people defending her. And that’s a superstar to me: When you transcend politics.”

But then, on the Woke Wide Web, what makes a fan today? The ones who think their idols can do no wrong, or those whose devotion is unshaken despite it all? “The conventions of film fandom have usually been shaped by a large, amorphous group of followers, and it is difficult to identify any unifying thread in these communities,” explained Mazumdar. “Fans are known for their obsessive forms of adulation and are usually distinguished from spectators and audiences who engage with the world of images analytically.”

“With social media, fandom is increasingly becoming politicised, and as a collective group, fans can produce certain effects that can have immediate consequences,” said Mazumdar. Whether it’s gushing or trolling, every minor incident gets amplified online and becomes newsworthy. “This is a newfound power felt by fans that spreads to form a different kind of consensus. Perhaps what has changed is the context of social media, where passionate adulation and hatred co-exist in a new battleground.”

To exercise that power – that is, to type, tweet and shout at your idols all day in hope of some response, any connection – takes real work. As fandom gets more complicated, does Gen Z have the time or inclination for it? There’s no one answer. Shingare, for example, also admires pop star Harry Styles, loves anime, Keanu Reeves, and finds value in it. “We all have that one person that we look up to. And the people we admire says a lot about who we are and who we want to be.”

“I’ve met people who are crazy fans of Tollywood actors and actresses. They put them on a high pedestal, they look at them in this divine light. I can’t comprehend it,” said Kusum Priya, a student of architecture from Hyderabad. “I’m not a fan of anyone. I’m excited by aesthetics and visual characteristics.” Priya would much rather watch recent films Qala or Everything Everywhere All At Once than any hype-fuelled juggernaut, or discuss Kylie Jenner’s lion head-ensconced Schiaparelli dress and the latest uproar in the Kardashian household without being obsessive about them.

“Personally, I don’t feel the superstar tag holds as much importance anymore,” said Chandrashekhar. “I saw Rajkummar Rao and Huma Qureshi at DIVINE’s performance at Lollapalooza Mumbai. Just seeing them there really humanised them for me.” In a past life, being that “important” would mean a big no-no to mingling with the masses, even if it was in an elevated VIP section. “But there they were, standing inside a racecourse, enjoying music just like the rest of us.”

As I write this, Pathaan is closing in on Rs 1,000 crore in global box office collections. Riding on that wave, DDLJ is being prepped for a wider release, beyond Mumbai’s Maratha Mandir that has loyally run screenings every day for the last 23 years. “In the end,” said Fawzia, “it’s all PR. But that’s something both Taylor Swift and Shah Rukh Khan know how to do: Keep the hype alive, no matter the number of years for which they disappear.”