For more end of year essays and analysis on VICE, check out 2022 in Review.

If you looked around today on any high street in Britain – or on social media – you might find it difficult to place which decade we’re in. The only clue would be that… it’s literally all happening. Every trend, every era, every reference is happening everywhere all at once. Colours, fabrics, cuts, themes, energy. We’ve been edging this way since 2020, but never has this been truer than in 2022, the first full and proper year out post-coronavirus lockdowns, the couple of years that altered our collective psyche.

Videos by VICE

Since the pandemic, microtrends have organically popped up on TikTok, with users describing grouped looks or aesthetics – bimbocore, Catholic chic – that might most accurately be described as “vibes” or “a mood”. Most of them exist for people to showcase specific fashion, interiors, films and behaviours that are matched together: the modern Pinterest board. There were enough of these mini-trends that we got fatigued enough by the media writing news blogs about them that we went “post-trendcore”, the media then declaring that the trends had gone too far and so had the blogs about them.

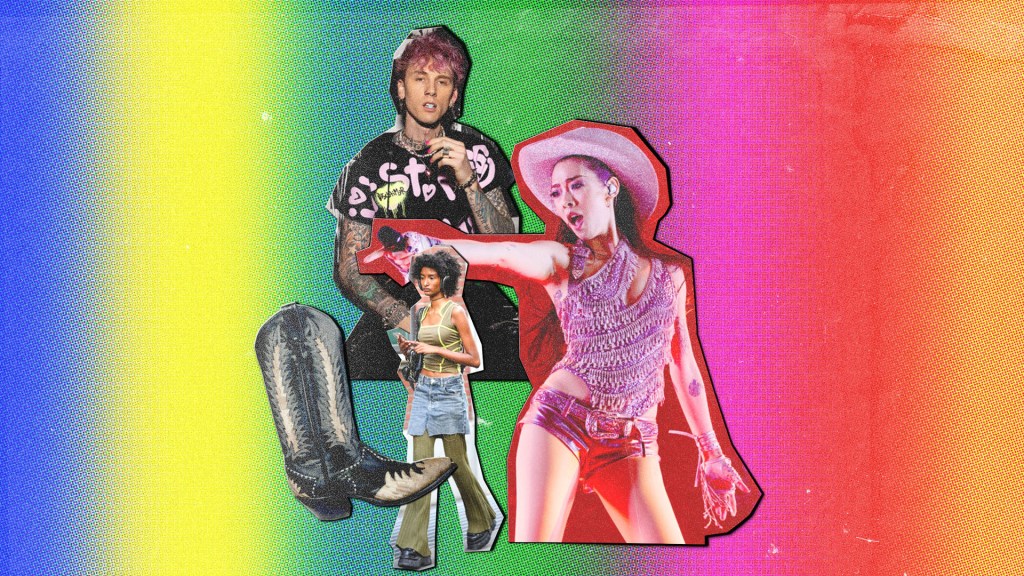

Elsewhere, fashion has drawn from every subculture under the sun (pop punk, alternative, indie, Y2K, goth, lolita). Music is no longer safely in the pop and hip-hop dominant era of the 2010s. To describe what’s going on today you could point to the aftermath of Machine Gun Kelly leading a pop punk revival. Or The 1975 doing a stripped back traditional Album album (11 tracks, a band in a room, each song recorded in only one or two takes). Or pop and rock artists like Rina Sawayama and Paramore referencing 00s British indie. Regardless, it’s disorientating and fragmented, while also providing – and I say this tentatively – refreshing space for every genre of music to thrive and every music fan to get what they want. To put it simply: What the hell is going on?

In his 2010 book Retromania, music critic Simon Reynolds described how contemporary pop culture in the 00s was “dominated by the re- prefix: revivals, reissues, remakes and re-enactments”, rather than the millennium “being the threshold to the future”. There has, he argues, “never been a society in human history so obsessed with the cultural artefacts of its own immediate past”. It’s strange to consider that in itself – why are we constantly revisiting the past in music, fashion and pop culture? How did we get trapped in a self-imposed time capsule machine? Whatever the answer, the pace of the nostalgia trip has gotten so fast its tripping over itself.

Previously, the 20-year cycle meant that pop culture trends came and went every 20 years. It needed to be that long: Any shorter and a trend would just be naff, corny or passé, rather than retro, inherently nostalgic and cool. That rule has rapidly been made obsolete. Now it’s more like five, 10 years. It’s not a reach to say that currently most decades are being referenced most of the time. How else did we reach a year in which pop punk, cowboy boots, sweatpants, diamanté jewellery, Regency-inspired outfits and drill music co-existed?

It feels as though two things are happening: These trends are disorientating and everywhere. Within this miasma of ideas and references, micro-trends are also coming in and out. The traditional life cycle of a fashion trend consists of five stages: introduction, rise, peak, decline and obsolescence. Where even a few years ago, a trend would last for a year or two, this whole cycle currently runs through from start to finish in months or even weeks.

It makes sense that this is happening now. The 00s babies are reaching adulthood and have only lived in this new retro-world Reynolds describes. They never experienced the 90s pop mania or the 80s or the 70s with all its uniqueness and difference. This melting pot of culture is all Gen Z have known and the amount of time they spend online with all of culture history a click or scroll away has flattened time – our entire past is there to be accessed and referenced.

This instant accessibility means that each trend is divorced from much of its original context. Regency-core fashion items don’t have anything to do with going to the opera, having a manor house or living without technology. Wearing alt-adjacent clothing doesn’t automatically mean you are into rock music, play guitar and skateboard. They’re sort of empty signifiers devoid of their fuller past meaning.

There are so many of these trends that it’s hard to tell which are actually real. Take indie sleaze, for example. If all was to be believed a year ago, this would be the year in which indie would take over again by way of Gen Z. Articles in Vogue, the Guardian and GQ proclaimed that girls would be swanning around looking like Kate Moss, white boys in bands would be the height of relevancy once more, skinny jeans would be an acceptable daily form of suffering and we’d all be taking high-flash photography on our nights out. This never happened.

Where 00s indie was somewhat revived was through the creations of millennials: the aforementioned Paramore and Rina Sawayama, both artists who lived through that era and wanted to pay homage to it. In April this year, i-D ran a piece headlined “Fashion has reached peak trendcore and we’re all tired”. Though it’s critical of how important these trends actually are, the writer ends on a positive note, suggesting that: “What this actually speaks to is a fascinating amalgamation of aesthetics that is blurring the lines of set style guidelines and expectations, which shouldn’t be taken too seriously. And while some folks might take offence at their precious subcultural symbols being co-opted by people outside of their cliques, most people truly don’t care.” It’s true that most don’t genuinely don’t: It’s washing over us like the wave of references it is.

The dark side of the trend cycle being shortened is that it’s inarguably happening, at least in part, because of fast fashion. Though we know of its devastating environmental impact, we are still buying cheap garments online. Instead of fashion being dominated by a couple of seasons and collections a year, companies push new clothes all year around and fuel our obsession with faster and faster micro-trends. As we’ve seen this year, as soon as something is coined on TikTok, it’ll be available to buy online.

What does all of this say about us? It’s reflective, of course, of the real information age. The fact we spent two years inside stuck to our screens. At the risk of being Charlie Brooker about it, it speaks to the lack of meaning and nihilism inherent in our lives now. We’re knowingly entering the final and irreversible stages of climate change and the end of the world feels imminent – that is the stage for this pop culture mess. We’re running through the greatest hits or Top 100 of the past few hundred years. It’s hard to make anything entirely different when we can’t imagine what the world might look like in five, ten years. Why, when we can just revisit specific and vibrant and weird and nostalgic times, would we even make anything new?

More

From VICE

-

(Photo by Dana Neely / Getty Images) -

(Photo by Bettmann / Getty Images) -

Collage by VICE -

Christmas sheet music and decorations. (Getty Images)