BELLO, Colombia – When her time came, 26-year-old Natalia Restrepo closed her eyes, kissed the cold metal cross that hung around her neck, and clenched the straps of a blue duffle bag.

Taking a seat on the bus, she put the bag beneath her legs. A padlock secured the contents. She checked the fourteen-hour route to Colombia’s Atlantic coast on her smartphone.

Videos by VICE

Then, she put her hands together and prayed.

“Maybe it was drugs. Maybe it was cash. I don’t know. All I know is they told me that if I couldn’t pay my debts, I needed to do this for them – to take the bag from here to there,” she told VICE World News. She asked to use an alias to protect her identity.

By “here” she meant Bello, a sprawling suburb of brick and concrete that climbs up into the foothills of the Andes, just outside of Medellín, Colombia, a city of four million. Restrepo took the bag from her hometown of Bello to Barranquilla on Colombia’s Caribbean coast. A local crime boss that had lent her money told her that if she didn’t do it, there would be consequences.

Restrepo lost her job as a make-up artist at a local boutique in Medellín after the pandemic hit. A single mother to twins for whom the father doesn’t pay alimony, she turned to a local loan shark for cash. But Restrepo’s debt quickly spiraled out of control.

“Over the past year, there are indications that there has been an increase in loan sharks lending to those in the black market or informal economy who have not been able to make money during the lockdowns,” said Jeremy McDermott, co-director at InsightCrime, a think tank that studies organized crime in the Americas.

Pandemic lockdowns around the world have made people feel forced to turn to predatory lenders, according to the Global Initiative Against Transnational and Organized Crime (GITOC). The GITOC found evidence that organized crime groups often preyed on victims of personal bankruptcy, the rate of which increased during the pandemic.

In Latin America, some lockdowns lasted for months. Unlike those with digitally-enabled professions, millions of people in the region who relied on manual labor to survive have seen their debts increase dramatically.

The pandemic amplified inequality in Brazil, Argentina and Colombia and lockdown measures increased unemployment to 10.6% in Latin America as a whole, according to the United Nations Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. The pandemic set back women’s inclusion in the labor market by ten years. Aflore, a micro-lender, estimates that the formal banking system excludes approximately 70 percent of people living in Mexico, Peru and Colombia. Vulnerable and distrustful toward the banks, some of this giant chunk of the population turned to local, informal lenders for fast money.

In Restrepo’s neighborhood, a lending system known as the “gota a gota” or “drop by drop” allows people to take out fast money loans. But interest payments can be as high as 20 percent per month. Before she knew it, Restrepo was up to her eyeballs in debt.

“‘Gota a gota’ usually starts with a very small amount of money but it’s a snowball effect and eventually, people usually put up their homes as collateral out of desperation. And when this happens, and they can’t pay, they lose their homes,” says Manuel Jimenez, co-founder and chief operations officer of Aflore. Sometimes lenders force the borrower to put their house up for sale so as to be able to pay their debts, and there have been cases where the loan shark has just taken control of the house, often using violence, said Jimenez.

The “gota a gota” loan model was born in Medellín at a time when drug cartels ran amok. In the early 2000s, lower-ranking narcos began lending out cash through informal credit shops. It was a way to launder their drug money. A group of drug-traffickers born out of Colombia’s vicious paramilitary organization started using violence as a debt collection method.

Loan sharking was one way for drug traffickers to manage the mafia’s cash. Indebting the masses was a way to expand social capital and control.

“Clan del Golfo were pioneers of the ‘gota a gota’, but now it involves lots of different groups. Not paying usually means threats of violence, or those who fall into debt with the criminals are sometimes forced to do jobs for them, like hiding or moving drugs,” explained McDermott.

Failure to pay can also mean getting killed. “The bloodletting that you see related to these types of extortion payments in Latin America is unmatched by the rest of the world. The amount of money people die for in Latin America is painful. It happens over dollars and cents,” says Tuesday Reitano, deputy director at the GITOC.

“Somehow, the threat of violence alone seems to have very little collateral anymore in Latin America.”

Over the past two decades, the Medellín lenders have exported “gota a gota” across Latin America. Earlier this year in Argentina, a group of Colombian loan sharks were found to be operating in the city of Rosario. In Guayaquil, Ecuador Colombians dominate the usury business. Non-Colombian organized crime groups have copied the “gota a gota” loan model and used it in other cities as well.

During the pandemic, governments in Latin America have tried to shovel aid to vulnerable groups, mainly through cash transfers. But the United Nations says it was not enough to cover the basic needs of households like the one Restrepo is responsible for. Organized crime is capitalizing on the need left unmet by governments.

“Now, because of the pandemic, transnational criminal organizations are expanding into other sectors, including those that the state is simply too overwhelmed to handle,” writes José Miguel Cruz and Brian Fonseca, both political scientists at Florida International University.

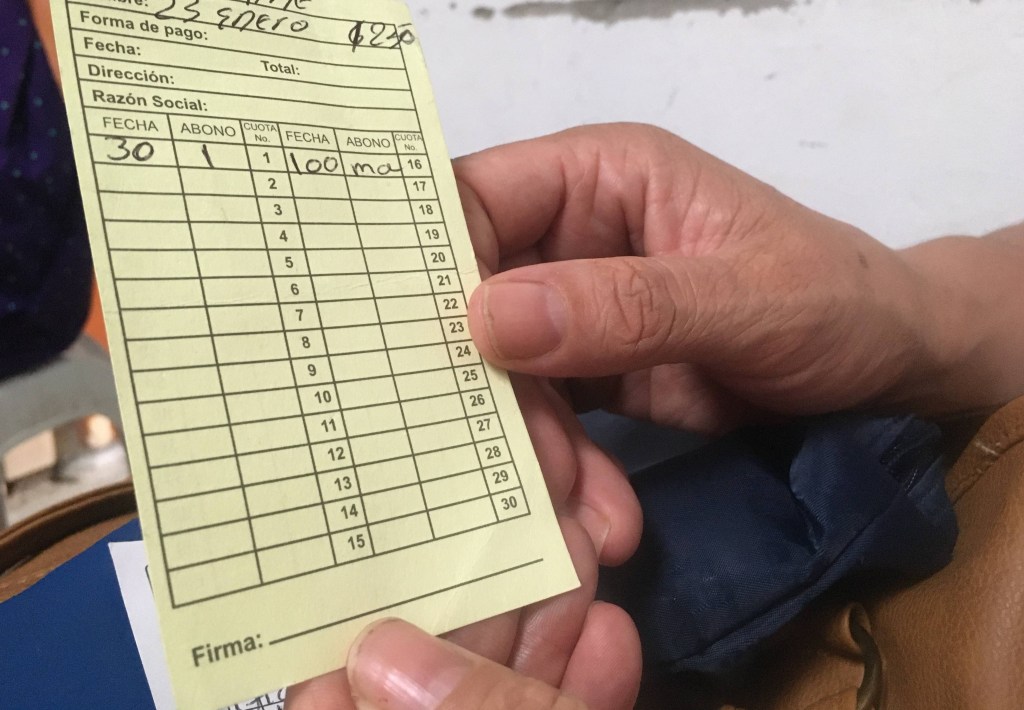

Back in Medellín, another victim of the pandemic 42-year-old Jacqueline Acevedo clutches a yellow card that shows her payment schedule for a “gota a gota” loan. A few months ago, she moved out of her house because she couldn’t afford the rent payments. Acevedo earns a minimum wage of around 900,000 pesos, or about $250, a month. Every fifteen days, a man on a motorcycle comes to collect a 350,000 peso, or $100, interest payment. With the help of family, she hopes to pay off the last of her debts in three months.

“They say the lenders are bad guys. But they really aren’t. They help me. What would I do without them? Where would I get the cash?” she says, shrugging off the rumors that loan sharks harm to those who don’t pay.

A “ping” dings on Acevedo’s phone. It’s Patricia, one of the lenders. Acevedo referred a friend to Patricia. But now the friend can’t make a payment.

“You need to answer for this,” Patricia writes her on WhatsApp. “If your girl won’t pay, then you need to make her pay. So, make it happen. Or we will.”