This article originally appeared on VICE Belgium.

Five years ago, the gilets jaunes movement took over France. Protesters who were unhappy with the rising cost of living gathered every week from November 2018 to February 2019 to demonstrate against capitalism and inequality, with demonstrations held until March 2020.

Videos by VICE

The protesters initially gathered at roundabouts across the country, and then moved into the big cities’ streets and squares. Demonstrations often descended into chaos, with frequent violent clashes with the police. Every weekend, French riot police threw explosive grenades into the crowds, mutilating and blinding multiple protesters.

French photographer and art gallery technician Steven Monteau went to many demonstrations in his city of Bordeaux. “Even though some media outlets gave them a bad reputation, I’ve never felt so much humanity and hope for a fairer future,” he tells VICE. At the protests, Monteau often saw people getting injured: “Some friends and I started collecting everything we could to learn more about the weapons littering the city.”

One of Monteau’s friends, Antoine Boudinet, lost a hand in December 2018 because of a GLI-F4 grenade – a bomb containing 26 grams of TNT, which was used for crowd control in France before being banned in 2020.

Monteau wanted to find some way to help him and other victims. He thought of decorating a Christmas tree with some of the grenade shells he found on the street, and auctioning it off to pay for their medical and legal fees. Monteau suggested the idea to Boudinet, but he refused. “In France, they mutilate you, but they also take good care of you,” Boudinet told him.

French police came under particular scrutiny for the use of the flash-ball, a projectile designed not to break the skin. Although non-lethal, these devices can severely injure people – just ask the demonstrator lost an eye to one.

Monteau and his friends manipulated the weapons they found on the streets to get ideas. “We aimed a flash-ball against area of our eyebrow to imagine what a high-speed impact could do,” Monteau said. “That’s what inspired me to use a flash-ball as a camera viewfinder.”

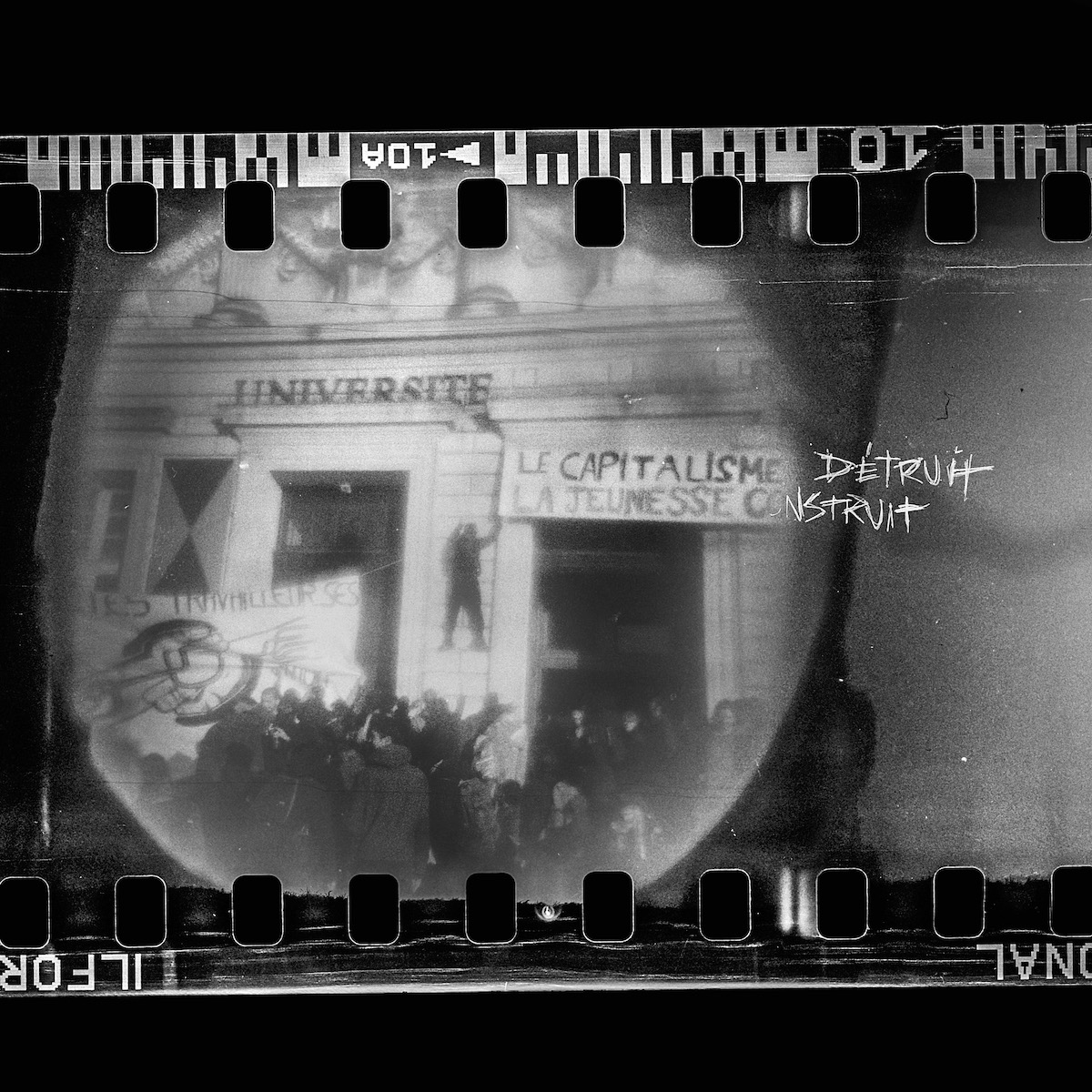

Created over four years ago, the camera is entirely made out of police weapons, except for the plastic see-through part of the lens. “The shutter comes from a GLI-F4 grenade, and the lens from a tear-gas canister,” Monteau says, adding that he unwillingly had to learn a lot about police weapons to make the camera.

On the 1st of May, 2019, Monteau was at a protest with his camera. He got arrested and his device was smashed open by a police baton and seized. “It’s true, it looks like a bomb,” he acknowledges. “It’s made out of their bombs.” After inspection, his camera was finally given back to him when he left the police station three days later. “Legend has it that it was circulated around different police offices before being returned to me,” he jokes.

The camera still works despite that chaotic ordeal. “It’s now protected from police wrongdoing by a cardboard box marked ‘PRESS’,” Monteau adds. To Monteau, his images are “a return to sender”, he says. The police throw bombs into crowds; he returns that violence to them in the form of pictures denouncing their brutality: “an eye for an eye”, as he puts it.

The camera and its photos are quite experimental, and have become even more so after the photographer’s arrest. The police baton has left visible marks: The camera now has many light leaks, the film comes out a bit jumbled and the shutter release isn’t exactly reliable. This is all reflected in the photos, like its darkened corners. Monteau thinks this artistic effect reflects the context well: “It’s similar to what happens when you squint in a cloud of smoke.”

The story of the camera is also the story of the photographer’s own radicalisation, as the gilets jaunes movement marked a turning point in Monteau’s activism. Before the protests started, he was already running Le Volcan, a collective creative space in Bordeaux focusing on re-use and the circular economy. But the gilets jaunes made Monteau want to fight against the system instead of living outside of it.

“People say photojournalists have to be impartial, but I want to be part of the movement,” Monteau says. The gilets jaunes don’t take the streets every weekend anymore, but the photographer continues to capture other social struggles with his camera to “create art with the devices used to control the population”.

His photos have been shared on Instagram and exhibited at Le Volcan in May 2019, to mark the six months since the beginning of the protests. This visibility allowed him to get to know other radical activists and photograph them, too.

Monteau’s camera captures violence, both physically and symbolically. These days, he’d like to connect this world with his day job at a contemporary art gallery. “A lot of people who aren’t particularly militant were hooked by my work,” he explains, “even before they ever questioned the weapons cops use.”

Unfortunately, he’s had to pay a price for his art and activism: In March 2023, during a demonstration in Paris against the French government’s pension reform, the police hit him with a baton and Monteau ended up at the hospital with a head trauma. Five year after the gilets jaunes, protesting in France still isn’t without risks.

Scroll down for more pictures: