In the wake of a high profile, ugly leak with devastating consequences for its users, Ashley Madison is sending DMCA notices left and right, playing copyright whack-a-mole with every new upload or posting of the hacked data. The information dump hasn’t been driven offline—just made a little more difficult to find—but are these DMCA requests valid? The answer is likely not, and Ashley Madison may even be perjuring itself with each request.

The Ashley Madison leak is very scary. The use of this information is morally fraught, and it has the potential to ruin people’s lives. But copyright law is an inappropriate way to deal with ingrained social antipathy to perceived sexual deviance, or with Ashley Madison’s negligent security practices, or with the company’s failure to actually delete information after taking money to delete it.

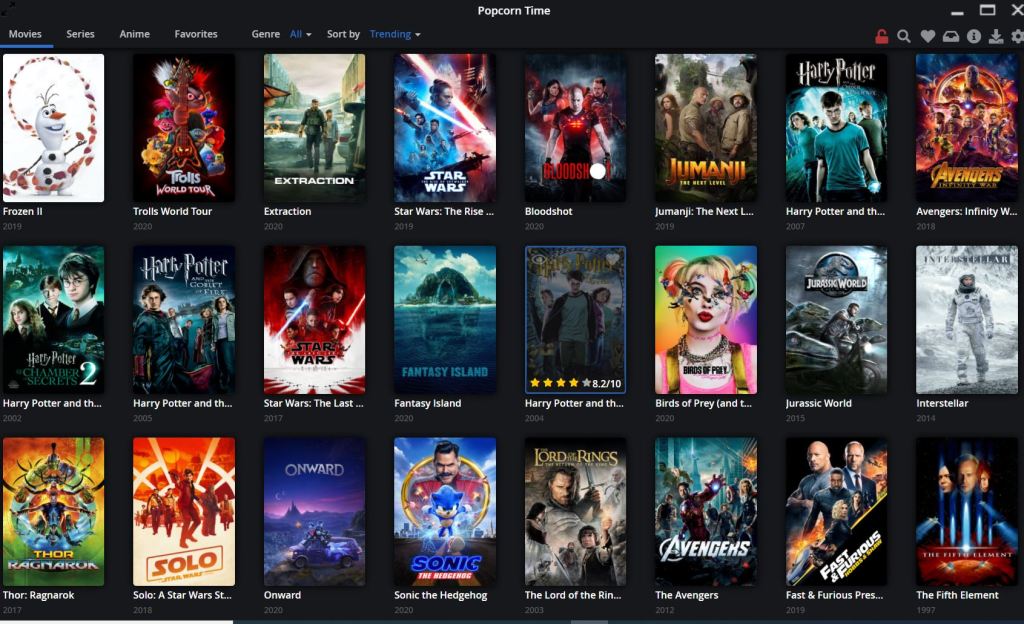

Videos by VICE

Yesterday we wrote about how a DMCA request from Ashley Madison took down a tweet from Motherboard contributor Joseph Cox. The tweet had embedded a screenshot of two cells from a spreadsheet.

Image: screenshot of author’s removed tweet

One cell read “Institution” and the other read “Acct #”. This is hardly the stuff of copyright. Emails, names, credit card numbers, credit card transactions, and other lists of bare facts aren’t copyrightable unless arranged with sufficient originality, and automatically dumping this data into an excel spreadsheet probably isn’t enough. In fact, in 1991, the Supreme Court ruled that telephone directory white pages cannot be protected by copyright law.

Of course, not everything in the dump is uncopyrightable. The text from user profiles (“I’m a very successful good looking well built married man looking for some excitement in life”) is copyrightable, but the copyright belongs to users. It could only be transferred to Ashley Madison through either an operation of law or “an instrument of conveyance, or a note or memorandum of the transfer” in writing and signed by the users. The terms of service at the moment contain a provision (added in 2013) stating:

You acknowledge and agree that all content and materials available on our Site are protected by either our rights, or the rights of our licensors or other third parties, of publicity, copyright, trademarks, service marks, patents, trade secrets or other proprietary rights and laws.

It’s vague and not clear about a transfer of ownership, and in any case terms of service aren’t signed by users. The validity of even an express assignment of copyright through terms of service is already dubious. Craigslist tried this back in 2012, and Ashley Madison’s case is worse.

Weirdly, the most compelling case for copyright infringement in the initial dump is the tagging system. Some of the files include text from user profiles, tagged with numbers that correspond to preferences and kinks and other descriptions, ranging from “Drug Free” to “Bondage,” and the dump also includes a key mapping the numbers to their “meanings.”

This arguably resembles a dental taxonomy system found copyrightable in the 7th Circuit in 1997, and maybe even the Java API in Oracle v. Google (which the Supreme Court declined to review earlier this year). But not only is the resemblance fuzzy, this area of copyright is also extremely contentious. The Copyright Act clearly states that systems and methods of operation aren’t copyrightable, and noted copyright scholar Pamela Samuelson has recently written on the errors in the Oracle v. Google decision.

Even if Ashley Madison is perjuring itself over and over again, it is unlikely to suffer any repercussions

Additional information was leaked today, and the inclusion of internal documents and emails means the copyright case there might be stronger—though still dubious. (See, for example, the last paragraph of Eugene Volokh’s analysis of the Sony dump.)

In summary, the Ashley Madison dump prior to August 20th contained a mix of uncopyrightable content, content owned by users rather than Ashley Madison, and a system of organization that might fall under a gray area of copyright currently subject to massive academic controversy.

DMCA notices require a “good faith belief” that there is infringement, and any lawyer worth their salt would know that the DMCA is wholly inappropriate to take any of this down, because either the posting does not infringe Ashley Madison’s rights, or whatever case for infringement can actually be argued is a reach to the point of being ridiculous. On top of that, a valid DMCA notice must contain a statement under penalty of perjury that the “complaining party is authorized to act” on the copyright owner’s behalf. Someone out there might indeed be committing an awful lot of perjury!

But even if Ashley Madison is perjuring itself over and over again, it is unlikely to suffer any repercussions. Proving an absence of “good faith” has been very difficult since the Lenz case (about a DMCA takedown of a YouTube video of a dancing baby), and because Lenz also limited attorney’s fees, the economics of lawsuits over DMCA misuse don’t make any sense.

What’s truly disappointing is that Twitter honored an invalid notice. In the first half of 2015, Twitter declined to honor approximately 33 percent of all notices, deeming them to be invalid. Similar numbers are reported by WordPress, which has in the past gone to bat for its users by suing over DMCA misuse. By allowing Ashley Madison to get away with DMCA misuse, Twitter is aiding and abetting them in censoring journalists at Motherboard and other publications.

“Ashley Madison is in cornered-animal mode,” said Parker Higgins, director of copyright reform at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, to Fusion. But how many times does a panicked company have to commit perjury before it really ought to know better? Ashley Madison has treated its users shamefully, and is now treating the law shamefully as well.

Correction 8/20/15: The article previously stated that Twitter honored invalid DMCA notices, plural, from Ashley Madison. A Twitter representative reached out after this story was published to explain that Twitter only acted on one. Although Ashley Madison has sent out many invalid notices to many different parties, according to Twitter, this is the only instance in which the company acted on a DMCA notice from Ashley Madison. The sentence has been corrected to reflect this.