For 30 years, Russell Cooper’s life was dominated by a crippling heroin addiction. He first tried it with a friend in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside in his early 20s, and it made all his self-esteem and anxiety issues disappear. But the cost was the breakdown of his marriage, getting fired from his railroad job, and serving seven years in prison for robbing banks to support his habit.

Cooper was homeless after he was released and the addiction became more powerful than ever. He would do whatever it took not to get dopesick, the painful withdrawal. Still, he was desperate to lead a functional life, though multiple attempts to kick the cravings with methadone and treatment programs got him nowhere.

Videos by VICE

In 2011, an employee at the Crosstown Clinic next to his homeless shelter asked him to join the research study there providing pharmaceutical heroin — known by its pharmaceutical name diacetylmorphine — and other injectable opioid substitutions to long-time, chronic, users like him. It’s the only place in North America that offers this controversial treatment. Since then, Cooper, now 55 years old, has been injecting himself twice a day with prescription heroin under a doctor’s care. He’s one of a select number of patients with severe opioid addictions who receives a pharmaceutical version of the drug that almost ruined his life — and now it’s the reason he feels human again.

Having a steady and clean supply means Cooper has stopped committing crimes, and recently rented his first apartment. The prescription injection doesn’t make him feel high and out of control like before. “You get your warm glow, but it’s different from when you’re desperate with nothing, ducking in a doorway,” he said recently after taking one of his doses. He’s thinking about going back to school and upgrading his first aid certification.

Like Cooper, the couple hundred or so patients who have flowed through the Crosstown Clinic — most of whom average around 15 years or more of chronic heroin dependence — experience a dramatic boost to their physical and mental health once they switch from using street heroin and other opioids to the pharmaceutical alternatives like diacetylmorphine. But health agencies in North America have long denounced or ignored heroin-assisted treatment.

“You get your warm glow, but it’s different from when you’re desperate with nothing, ducking in a doorway,”

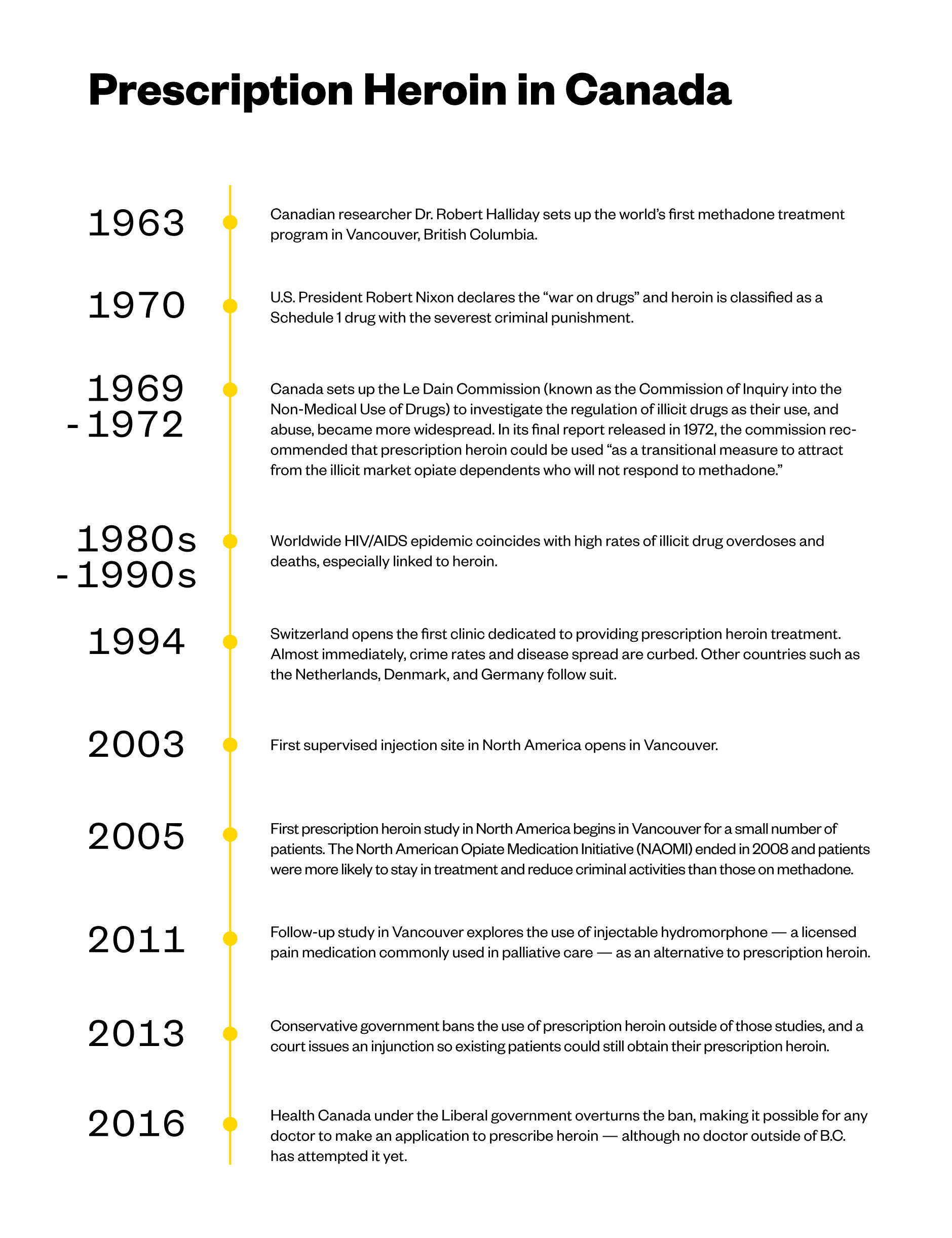

But because of the success of the Crosstown program, and others like it that have existed in Switzerland and other European countries for decades, Canada’s health minister recently made it possible for doctors to prescribe pharmaceutical heroin to their patients for the first time — legalizing access to a prescription form of what’s arguably the most reviled drug in the world. It’s the latest piece of progressive drug policy to come from a Liberal government that has expanded safe injection sites and will legalize recreational marijuana later this year. All steps that are radically opposed to the administration of President Donald Trump, which appears to favor draconian drug laws and the criminalization of addiction.

However, existing barriers means that expanding access to prescription heroin will be time-consuming and difficult in Canada, which is grappling with an overdose epidemic fueled by an increasingly unreliable, and toxic, illicit drug supply. Thousands of lives have been lost — long-time addicts and casual drug users alike. And as health authorities scramble to respond, some argue the government is simply not going far enough to address the root causes of the health crisis.

**

Crosstown

Since 2006, Eugenia Oviedo-Joekes has been the lead investigator of the Crosstown Clinic’s prescription heroin studies, fashioned after a similar study she worked on in Spain more than 10 years ago. She’s cautiously excited at the prospect that more people in Canada beyond the small cluster in Vancouver might benefit from having access to heroin assisted treatment. It’s long been her goal to see the program replicated in other countries, but especially the U.S. and Canada, both of which are grappling with an opioid overdose crisis that’s been described as the worst drug safety emergency.

“The frontline workers, patients, and people who are using street opioids are pushing very strongly to decision-makers to make our treatment available to not just these selected people,” she said in an interview from Vancouver. “I would call them the lucky ones, but really no one is lucky in this situation.”

The first study at Crosstown was called the North American Opiate Medication Initiative (NAOMI), and tested whether pharmaceutical heroin was more effective than methadone — an oral narcotic prescription commonly used as a substitution for illicit opioids. NAOMI was supposed to be a joint study between American and Canadian researchers, but the Americans had to pull out due to a lack of funding.

“I would call them the lucky ones, but really no one is lucky in this situation.”

The results revealed that prescription heroin was indeed more effective than methadone for this subset of chronic heroin addicts. On top of that, they engaged in far less criminal activity, and they were getting counseling and other healthcare treatments, often for the first time. A follow-up to NAOMI, the Study to Assess Long-term Opioid Maintenance (SALOME) found that hydromorphone, a pain medication that’s licensed in Canada but is not designed to treat addictions, is just as effective as prescription heroin. The majority of patients couldn’t tell the difference. This is significant because hydromorphone is licensed in Canada, and therefore more easily obtained than diacetylmorphine — however most doctors are hesitant to prescribe it off-label as a heroin substitution.

On the financial side, it costs an estimated $48,000 per year to fund the healthcare and criminal justice costs for someone who is dependent on illicit opioids. Whereas it costs around $25,000 per year to provide that person with heroin-assisted treatment.

Though the Crosstown study results have shown the treatment to be overwhelmingly effective, with at least two patients now completely drug-free after spending most of their lives addicted to opioids, Oviedo-Joekes says the logistics of getting the drug itself and overall timidness of most Canadian physicians when it comes to controversial treatments could get in the way.

Intense federal restrictions around prescription heroin — diacetylmorphine or diamorphine — puts the onus on doctors to apply through Health Canada’s Special Access Program for approval to import the drug for each patient. Only three B.C. doctors, all working with Crosstown, have ever applied to prescribe diamorphine. Oviedo-Joekes says the application process is like a full-time job in itself, something that most doctors can’t add to their heavy workloads.

Once Health Canada approves, the drug must be imported from a small company in Switzerland called DiaMo, and only in quantities for six months’ worth of doses, after which time the process must be repeated. This whole process is designed to provide special drugs on a one-off basis for patients, and was never meant to help supply prescriptions on a wide scale, though Health Canada has said its staff would be open to working with interested doctors in navigating the process.

“We have so much evidence supporting heroin-assisted treatment, it’s not even funny.”

“We have so much evidence supporting heroin-assisted treatment, it’s not even funny,” Oviedo-Joekes said. “I have never heard of a doctor telling a patient that two medicines work, but then saying that only one or neither is available … Nobody does that with any other illness,” she continued. And while the treatment might only be relevant for a small, exclusive group of drug users, it can have a wider impact on the community.

“We should be pushing for both right now, and the fastest would be the hydrophone. And we need to work very hard to license the diacetylmorphine at the same time.”

**

The Swiss model

Switzerland was the first country to open supervised clinics offering prescription heroin in 1994 in response to its own illicit heroin crisis and having the highest rates of HIV/AIDS in Europe. Public health authorities found that methadone provided nowhere near the same effect as street drugs, so users had very little incentive to stay on it.

The Swiss Federal Health Ministry has since opened more than 20 clinics providing heroin-assisted treatment to around 1,500 people per year, and the results show a steady improvement in overall health as well as the socioeconomic situation of patients. It’s also helped push back against the stigma associated with people who use drugs. The program is run at the federal level, so that access is guaranteed in each region. The supply is transported to clinics in sealed containers in armored cars overseen by armed guards. The pharmaceutical company that produces it stores the products in two secret locations ahead of the clinic deliveries, which happens a few times per year.

“It’s become part of our overall addiction strategy, because people need access to different types of treatment in order to recover. It’s quite simple,” Catherine Ritter, a government specialist who oversees the Swiss program, said in an interview. “It’s a normal thing here, something that’s just integrated. But for most countries it’s not, and for us it’s very surprising that there’s such resistance in places like Canada.”

Ritter added that the illicit drug trade in the country has also taken a hit. “The larger offer of treatment, the more impact you can have on the black market,” she said. “If the program works well, people will not be interested anymore in going to the streets for heroin. It was a drastic change at the beginning for us, because the streets used to have open drug use. Then the demand for street heroin decreased.”

“The larger offer of treatment, the more impact you can have on the black market.”

One of the downsides, said Ritter, is that, like the Crosstown program, Swiss patients must use their prescription inside the clinics, something that’s time consuming and can impose restraints on their lives. The country also relies on DiaMo to supply the clinics, which means prices can be high because the competition is almost non-existent.

DiaMo’s spokesperson, Mathias Markert, wrote to VICE News in an email that he won’t disclose much information on the company to the public “otherwise we may endanger availability of the product our patients rely on. Any disruption of supply chain or disturbance at the clinic sites due to overwhelming public interest may endanger the progress in treatment our fragile patients made so far.”

Markert added that when it comes to Canada, “cooperation concerning filing for market authorization of diamorphine [there] is in evaluation.”

**

Safe injection

Dozens of heroin users poured into The Works clinic in Toronto one morning last month. The clinic, run by the city’s public health board, provides methadone treatment and other harm-reduction services like clean needles. There used to be about five or six overdoses in the clinic per year, and now it’s almost a daily occurrence. A woman walks in and screams that the heroin she just took was actually fentanyl, and she feels like she’s going to die.

Dr. Leah Steele, who helps run the clinic, can think of several patients on methadone who would benefit greatly from prescription heroin. “We see a really significant proportion of people on methadone still using significant opiates and other street drugs. They just can’t stay on methadone. For whatever reason, methadone just doesn’t work for them,” she said.

One 32-year-old patient, who wished only to be identified as Steven, has been struggling with heroin addiction since his foster brother introduced it to him at age 16. “I’m going to a treatment facility next week to try to get off methadone all together,” he said. “But I don’t feel good about it. People don’t tell you this, but methadone is like serving a death sentence. It makes me feel like a walking zombie. And I’m still using all the time. And now the streets are flooded with fentanyl. Heroin is supposed to be white or brown, now it’s every color of the rainbow.”

“People don’t tell you this, but methadone is like serving a death sentence.”

He says he tried to get into the NAOMI study years ago, but didn’t qualify. He’s going to try his best to stick with the recovery program, but is also holding out for the day that prescription heroin comes to Toronto.

Though the numbers are two years out of date, drug policy experts estimate that Toronto has seen a 73 percent jump in overdose deaths over the last decade, likely due to an increase of synthetic opioids like fentanyl and its even deadlier cousin carfentanil tainting the illicit drug supply.

This week, Toronto Public Health officials recommended that the city offer prescription heroin as part of its opioid overdose strategy. It’s one of the first times a municipal health authority outside of B.C. has openly called for the treatment, as well as hydromorphone. Under the proposal, the drug should be offered only at the city’s harm-reduction and methadone clinic, The Works, which is set to become one of the city’s first safe injection sites. The only safe injection sites in Canada are in B.C., with Toronto and Montreal expecting to open theirs within a year.

While many addictions leaders across the country welcome any efforts to expand access to prescription heroin and other evidence-based solutions, Benedikt Fischer, a senior researcher at Toronto’s Center for Addiction and Mental Health who’s studied heroin-assisted treatment, points out that such a treatment is designed for a small fragment of heroin users. And further, he adds that heroin use has generally declined here.

“The opioid crisis now is mostly prescription opioid users, a lot of them come from a different socioeconomic and also clinical profile from the typical population of people who use heroin, so heroin prescription treatment may simply not be appropriate in most circumstances,” Fischer said. “Heroin prescription treatment is not the mass solution for the opioid crisis as it presents itself currently.”

“Heroin prescription treatment is not the mass solution for the opioid crisis as it presents itself currently.”

The fact that it’s being talked about more as a broader solution to the overdose crisis points to the fact that Canada still isn’t very well equipped to deal with it, he added.

“Do not mistake my words as speaking against heroin-assisted treatment,” he said. “I’ve pushed it for many years, but talking about it this way is about 20 years too late.”

Hakique Virani, an addiction medicine specialist at the University of Alberta, said it’s good for health authorities dealing with the opioid crisis to have more options available such as heroin-assisted treatment.

However, he says prescription heroin should not serve as a substitute for the decriminalization of drugs, especially as many people dying from are not actually suffering from addictions. Numerous drug overdose deaths have occurred in recent years among casual drug users unwittingly ingesting street drugs contaminated with fentanyl or other highly potent synthetic opioids.

Although the Liberal government has promised to legalize marijuana for recreational use as a way to eradicate drug trafficking, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has repeatedly stated he will not legalize or decriminalize other illicit drugs.

“Decriminalization would have further reaching impacts in terms of the safety of substances, and it’s a critical part of solving the opioid crisis,” Virani wrote in an email. “We still need to see a drug policy environment that removes the incentives for drug traffickers that result in a more toxic supply.”

Updates on how the Canadian government has made it easier for communities to open safe consumption sites, and import prescription heroin can be found here and here

More

From VICE

-

Photo by GIUSEPPE LAMI/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock -

-

Image Credit: Natalli Amato -

Adderall