This article appeared in the May issue of VICE magazine. Click HERE to subscribe.

On the afternoon of September 30, 2015, 23-year-old Little Huang stood on the roof of the 11-story Shenzhen Health and Family Planning Commission building, ready to jump to his death. In the lot below, Chinese officials’ cars looked about the size of matchboxes, and the clamor of a nearby construction site filtered up as a dull hum. As Little Huang peered through the light haze toward the hills of Hong Kong, he dialed a 25-year-old man named Junjun. “We’re on the roof,” he said. “Bring alcohol and water bottles.”*

Videos by VICE

Junjun exited the metro at Cui Zhu station, stopped for rice alcohol and water bottles, then rode the elevator of the white-tiled building to the tenth floor. There a staircase wound up to the crumbling concrete roof, where he found that Little Huang had now scaled even higher, to the top of a mechanical shed that seemed to sway in the breeze over the building’s edge. Two other young men who Junjun recognized, Mr. Wang and Mr. Peng, stood with Little Huang. Junjun was nervous, but Little Huang cajoled him to climb up, too. The men wore matching white ball caps. Characters on the front explained the reason the men might jump: “Black-Hearted Men’s Hospitals Destroyed Our Well-Being.”

All four men, like more than a thousand across China who communicate with one another in online patient chat groups, say they were duped into surgeries that doctors worldwide have determined pose great risk and have little scientific merit: a dorsal neurectomy that severs penile nerves, ostensibly to cure premature ejaculation issues, though Chinese physicians sell the surgery with whatever explanation will likely get the person on the operating table. As a result of the surgeries, Junjun, Little Huang, Mr. Wang, and Mr. Peng’s penises have gone completely numb, they can’t get full erections, and some experience searing pain, probably from neuromas, which result from nerve trauma. No known corrective surgery or therapy exists. (In this story, these victims are referred to by nicknames or surnames.) All four men, who are in their 20s, may never have offspring. The men, in turn, refer to themselves as “China’s 21st century eunuchs.”

Physicians at private clinics have bargained with patients during surgery, female patients have been tricked into aborting healthy fetuses, and there have been many documented deaths as a result of physician negligence.

Sham penile surgeries are just one part of a much larger system of poorly regulated and corrupt private healthcare in China. In other instances of medical malfeasance, physicians at private clinics have bargained with patients during surgery, female patients have been tricked into aborting healthy fetuses, and there have been many documented deaths as a result of physician negligence. Pseudoscientific medical devices are in wide use, as is the practice of proffering false diagnoses, as more than 60 private hospitals have done to Chinese undercover journalists in the past six years. Meanwhile, the number of private hospitals in China is blossoming—between 2005 and 2015, 9,326 new facilities opened their doors. Today they make up about half of all hospitals in China. That proportion will likely grow as ongoing Chinese healthcare reforms aim to increase private investment in the sector and government-run insurance schemes expand to cover private healthcare facilities. American companies including Morgan Stanley Private Equity Asia, a division of Morgan Stanley, are pouring in millions of dollars as well.

On May 2, China’s internet regulator announced it would investigate Baidu, China’s equivalent of Google, which is the dominant source of traffic for private hospitals. Before Wei Zexi, a 21-year-old college student with a rare form of cancer, passed away on April 12, he publicly accused Baidu of promoting false medical information that led to his spending 200,000 yuan [about $31,000] for cancer treatments supposedly developed by Stanford University. A Chinese journalist showed the treatments held questionable medical value and that Stanford did not partner with the public hospital, which had been contracted out to private entrepreneurs.

Back on the roof, by 3 PM, security guards, health officials, firemen, and police officers had clambered up to try to dissuade Little Huang, Junjun, and the two others from jumping. The men drank their rice alcohol and dialed local Chinese newspapers and TV stations. If they had to jump, well, they didn’t want to be sober. A small crowd gathered on the sidewalk, but the media never came.

At nightfall, the men remained on the mechanical shed, and the gaggle of health officials grew impatient. When one of them approached the foot of the structure, gazing up at the patients, Little Huang and Mr. Wang screamed out their demands: find experts to treat them; arrest the physicians and nurses who conned them; ban the surgery that had made them all “eunuchs”; and pay for them to collectively undergo medical testing, the first step in legally proving the harm the surgery had caused. Until now, more traditional petitions and street protests had failed to gain the men attention, so they vowed to stay on the roof until city health officials took action.

“You caused this!” Little Huang screamed, tears streaming down his cheeks. “Victims have come to you before, and you do nothing! If there was oversight of these hospitals, would this happen?”

Finally, hours after the suicide pact/protest began, health officials relented and said they would meet the patients’ demands, but only if they promised to come down to a negotiating room. The men were wary. Mr. Wang felt they needed to leave a bargaining chip on the roof. They chose Junjun—the meekest of the bunch. As the negotiations carried on, the men agreed, Junjun would remain on the roof’s edge, ready to jump.

“I told them if they left me, I wouldn’t stay,” Junjun said. “I wouldn’t be able to last on my own.”

Ten minutes after Little Huang, Mr. Wang, and Mr. Peng climbed down, health official Huang Penghui, who oversaw the clinic where Junjun had received the surgery, stepped forward. He held up his phone and told Junjun he’d sealed off operating room 7 in Shenzhen City Hospital, the clinic where the surgery was done four months earlier. Eventually, Junjun came down and looked at the phone himself. A photo showed a white strip of paper pasted over the door that read: “Sealed Off.”

“Look,” the official said. “What more can we do?”

After Junjun was found to have an enlarged prostate, he went online to look for medical care and wound up receiving unnecessary surgery that left him impotent.

By day, Junjun tests applications at an IT company. “If this didn’t happen to me,” he says, his voice high and wispy, “I’d be white collar in a couple of years, even getting married.” He is a small, pudgy man with full cheeks and big, black sorrowful eyes. “Now basically all I have left is the ability to pee.”

The story of Junjun’s treatment is typical. On May 9, 2015, he accompanied his colleagues to get a physical done at a health checkup center, an annual routine for many workplaces in China. Test results indicated his prostate was slightly enlarged with possible calcification. The physician recommended he visit a hospital.

Junjun wasn’t worried—he’d always been in good health. He didn’t know where to go for further testing. In reality, he had two distinct options: an overcrowded public hospital, where a physician might see a hundred patients each day, or a private healthcare facility. Businessmen from Putian, a city in Fujian Province, own most of China’s private hospitals and clinics. Their interests are united by the Putian Health Industry Association (PHIA), which represents some 8,600 Putian-owned private hospitals, or about 70 percent of China’s private hospitals. Many advertise widely on Baidu, and last year, using its collective influence, the PHIA boycotted the search engine, demanding an end to the annual aggressive price increases for keyword advertisements.

Junjun turned to Baidu for help. On his phone’s browser, he searched “prostate exam” and clicked on the first link. He didn’t know it was an ad; Baidu search results blur the line between paid and unpaid links. Once on the website for Shenzhen City Hospital, a chat popped up:

“:) Hello, I’m Shenzhen City Hospital’s online physician, what can I help you with?”

Junjun described his physical results, and the online physician quickly convinced him to set up an appointment for a prostate checkup. On job websites where private hospitals recruit these “online physicians,” the qualifications make clear that the position is for salesmen—many are paid on a commission basis. Baidu searches provide the traffic. In turn, PHIA-member hospitals in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou (China’s three largest cities by GDP) contribute 10 to 15 percent of Baidu’s advertising revenues, analysts at Nomura, a Japanese investment bank, estimated last year.

On the morning of May 16, 2015, Junjun went in for the checkup. The hospital was right in the heart of Shenzhen, where the skyscrapers partition the sky into distinct rectangles and squares. Dongmen market was nearby, too, and Junjun was looking forward to buying new clothes after the checkup.

A friendly nurse led him into an examination room, where a licensed surgeon, Dr. Tang Congxiang, waited with his assistant. When Junjun mentioned the possible prostate calcification, Dr. Tang said he would need another full physical done. The male assistant led him to the cashier, where Junjun paid $100.

The tests began—blood, urine, penile sensitivity, STDs, prostate exam, and semen analysis, for which Junjun was brought to a room upstairs and set up with porn videos. Then the assistant led him back to the lobby and told him to wait for the results.

Since Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms started the transformation of China’s economy in 1978, private clinics and hospitals have slowly opened and expanded into medical fields like STD treatment, gynecology, andrology (men’s health), and reproductive medicine, where patient demand for privacy is high, a detail not generally offered in public hospitals. Private clinics and hospitals advertise widely—on the radio, public busses and billboards, even packing discount abortion cards into pregnancy tests, to rope in patients. They provide such a large portion of advertising revenue for some local newspapers that when Qingdao’s Metropolis Convenience Daily published patient complaints of a PHIA-member owned men’s hospital in 2010, and the hospital president retaliated by leading a group of knife-wielding thugs to ransack the newspaper office and slash five reporters, it was the newspaper that ended up shutting down after all hospital advertising was pulled from its pages. The hospital remains open.

“It was serious. He scared me. He told me I needed to be circumcised. When I said I didn’t want to, Dr. Tang Congxiang just repeated it again and again.”

–Junjun

When the test results came in, the physician’s assistant led Junjun back to the examination room, and Dr. Tang questioned him about his sexual history. Junjun disclosed he was single and a virgin. Then Dr. Tang hit Junjun with the diagnoses: urinary tract infection (UTI), overly long foreskin, low sperm count with low motility, and prostate calcification. He was in bad shape—the root problem was the foreskin. Junjun’s long foreskin had caused the infection, he remembers Dr. Tang explaining, which in turn caused the prostate calcification and the ensuing prostate crystals. The foreskin had to go.

“He told me I needed treatment immediately,” Junjun says, even though he had no symptoms. “It was serious. He scared me. He told me I needed to be circumcised. When I said I didn’t want to, Dr. Tang Congxiang just repeated it again and again. He said other hospitals couldn’t cure these diseases, but their hospital had imported medical technology to cure these problems.”

Dr. Faysal Yafi, a professor of urology at Tulane University School of Medicine, told me a man who has a UTI is not generally circumcised unless recurrent infections become a problem and that alone prostate calcification and prostate crystals do not require treatment.

Oversight of private clinics and hospitals is minimal. Some so-called physicians work without licenses. Even those physicians with licenses generally rise through a separate vocational education system that requires less academic study, which oftentimes precludes them from positions in public hospitals. In online chat groups for private hospital hiring, physicians advertise their abilities by touting their “average patient spend,” meaning how much money they can get out of each patient. Most of the posts list figures in the range of $450 to $600 per patient, akin to China’s average monthly wage.

“I was a little bit worried and scared,” Junjun says. “I couldn’t believe all these things. But I thought, well, a doctor wouldn’t trick me.” Eventually, Junjun agreed to the surgery, and the doctor’s assistant followed him to the cashier and waited as Junjun paid $220 for the circumcision and anesthesia.

None of the dozens of patients I interviewed could articulate why they agreed to surgery or believed their diagnoses. But Zhan Guotuan, one of China’s pioneering healthcare entrepreneurs and an honorary chairman of the PHIA, offered clues in a 2014 interview with China’s Entrepreneur magazine. “There are tricks for scamming money,” he said. “One is the so-called hospital guide. After you enter, someone follows you like a shadow, like a retail salesperson, constantly brainwashing and scaring you… denying you the opportunity for independent thought or time to consult friends and family.”

“I wasn’t paying attention to the details,” Junjun says. “The assistant was always following me, leading me. I didn’t have any time to think.” He was soon on the operating table. Dr. Tang injected local anesthesia and began the surgery. During the course of the operation, Junjun recalls Dr. Tang telling him he had too many nerves. “It was my first time ever having surgery,” Junjun says. “I was scared.” So while he was anesthetized and on the operating table, according to Junjun, the doctor pushed him to agree to a dorsal neurectomy as well, to get rid of the extra nerves, for an additional $430. Not knowing what the surgery was, but told it needed to be done, Junjun agreed. (Shenzhen TV ran a short segment on Junjun that suggested the hospital had forged his signature on the dorsal neurectomy patient consent form. Dr. Tang declined a request for comment.)

After the surgery, Dr. Tang advised Junjun he needed to use an “imported medical device” to break up the prostate crystals, which would be urinated out. It was expensive, about $12 a minute, but he’d be healed in an hour’s time, the doctor promised. Again, the doctor’s assistant followed him to the cashier, where Junjun paid for the neurectomy and an hour of therapy with the device. He’d now spent $1,500, more than two month’s salary. The $150 in cash he’d brought along was gone, and now his bank account was empty too.

“I’d already done the surgery,” he says. “I thought, It doesn’t matter about the money, and I can spend a little bit more if it will cure me, so I said OK.”

The assistant led him upstairs to a room that held the imported medical device. It resembled an MRI machine, and a nurse operated it from a separate computer control station. When Junjun lay down on the machine’s patient table, a cylindrical fixture extended down toward his groin like a zooming microscope. Soon a red light beamed at his prostate region.

“I didn’t have any feeling at all when I was under the red light,” Junjun says. “I just saw the light coming out of the machine. I was in a daze. I don’t know what I was thinking.”

When an hour under the red light was nearly up, Dr. Tang returned. “The doctor said one hour wouldn’t be enough. He said I needed to do another hour. When I told him I didn’t have enough money, he said, ‘If you don’t have enough money, just borrow some. You’ve just done the surgery, so the treatment is most effective now. If you wait to do more red light, the results will not be the same.’” Junjun dialed a classmate, who came with a bankcard, and Shenzhen City Hospital charged another $740. He was led back to the machine for another hour of red-light therapy.

Though he was wary, Junjun returned the next day to continue treatment. When Dr. Tang suggested even more red-light treatment, at a cost of $930, he finally grasped he’d been conned.

“Doctors at public hospitals all know these private hospitals harm people,” Junjun sighs. “But no one stands up and says anything.”

In total, he spent $2,400, equivalent to about four month’s salary. He still owes his classmate money. After refusing more treatment, Junjun returned home to his parents’ small apartment and searched Baidu for information on the surgery that Dr. Tang had added. He read about the potential side effects. He read patient accounts of being duped. He read of their erectile dysfunction. “I fell down, down, into a type of hell,” he says.

The next day, Junjun called Dr. Tang and asked how he could do this to him. “He said it was nothing. He said I’d be fine.” Nurses at Shenzhen City Hospital told Junjun the same thing. “The nurse kept telling me how good this surgery is. She has a son, so I told her I’d pay for her son to get this surgery done. Her husband, too. They could all do it for free, on me.”

When Junjun went to a public hospital to understand his options, the doctor told him he’d been tricked. “Doctors at public hospitals all know these private hospitals harm people,” Junjun sighs. “But no one stands up and says anything.”

In coming weeks, his parents got involved, and after eight visits, the hospital agreed to return his treatment costs. “Return my treatment costs?” Junjun posted on an online Baidu forum. “They’ve turned me into a eunuch. I want them to cure me.” Reached by phone, Shenzhen City Hospital’s legal representative, Hu Jianfan, declined to comment for this story.

Shenzhen Luohu District Health Commission officials confirmed that Junjun’s neurectomy was tacked on mid-surgery but said Junjun had consented to the surgery. They claimed not to be responsible for medical devices and referred questions to the China Food and Drug Administration, who told me that their agency ensured the quality of medical devices and stated no private hospital is allowed to use unapproved medical devices.

Over the course of 15 months reporting this story, 25 public hospital physicians practicing in 15 Chinese cities said that patients scammed by private clinics and hospitals often end up in their waiting rooms. “Some public hospitals don’t even have an andrology department,” laments Dr. Jiang Hui, a professor at Peking University and chairman of the Chinese Society of Andrology, “so if you have these problems, and you see the advertisements, well, you get taken in and duped.”

Dr. Jiang believes in privatized healthcare, with regulation. “Oversight is difficult,” he says. “In China, there is no oversight.”

Shenzhen Qiaoyuan Clinic, where Little Huang received treatment. The Chinese characters on the building read: “Leading Men into a Healthy New Era.”

According to public records and interviews, Lin Jinzong owns Shenzhen City Hospital through his company Beijing Yingcai Hospital Management. He claims to own more than 200 clinics and hospitals across China and like most members of the PHIA, hails from the small town of Dong Zhuang, lying on the outskirts of Putian. Lin holds the position of supervisory vice chairman in the well-delineated PHIA hierarchy—only 15 men rank higher on the totem pole.

(Lin did not respond to repeated calls and emails to his three hospital holding companies seeking comment.)

Public records link ownership of all the clinics visited by the four Shenzhen “eunuchs” to members of the PHIA. Little Huang visited Shenzhen Qiaoyuan Clinic, owned by Xiao Hua through the company Bohua Industrial Group. Xiao also hails from Dong Zhuang, holds the rank of vice chairman in the PHIA, and operates at least ten other clinics and hospitals in China. A physician told Mr. Wang the dorsal neurectomy would cure his fertility problems at the Shenzhen Wanzhong Clinic, owned by Yang Xiandong, who operates four other clinics in Guangdong Province. Yang serves as a member of the Guangdong Provincial branch of the PHIA, as does Su Kaiming, who owns the Zhongya Clinic that Mr. Peng visited.

At the top of the PHIA pyramid is the chairman, Lin Zhizhong, the principal shareholder of the Shenzhen Boai Group, thought to be China’s largest private hospital holding company. His younger brother, Lin Zhicheng, owns a stake in Guangzhou Shengya Urology Hospital, which has given fake diagnoses to two undercover Chinese reporters in the last three years.** Two miles away sits Lin Zhicheng’s Modern Hospital Guangzhou, which in 2010 rebranded as Modern Cancer Hospital Guangzhou (MCHG) to draw late-stage cancer patients from Southeast Asian countries for “new and advanced, minimally invasive” cancer treatments. (One advertisement runs: “We create MIRACLES! We bring HOPE!”) MCHG’s chief oncologist, Peng Xiaochi, holds only a master’s degree in neurology. The president of a prominent public hospital cancer center familiar with MCHG, who asked not to be named, noted that most of the hospital’s advertising claims are false. “The hospital only cares about money,” he said. “They will never cure late-stage cancer patients.” Oncology is just one new business line for PHIA entrepreneurs—members now own and operate specialty clinics and hospitals for plastic surgery, dentistry, gastroenterology, ophthalmology, psychiatry, and many other medical fields.

The PHIA would likely not exist if it were not for Chen Deliang, born in Dong Zhuang Town in 1950. Today, at 65, he is small and frail, with a stooped back and the remains of his gray hair concentrated in two large sideburns, which reach down to his jowls. A gold Rolex and diamond ring adorn his skeletal left hand. He’s revered as the founding father of China’s private hospitals and holds the position of honorary chairman of the PHIA. “There were no doctors during the Cultural Revolution,” Chen told me on a visit to the $16 million Taoist temple complex he’s building in Dong Zhuang, explaining how he got his start as a traveling medicine man crisscrossing China with a mercury-based (read: toxic) home remedy for scabies that he pedaled on street corners. By the early 1990s, he’d branched out into private STD clinics. “We started making the big money,” Chen said, citing his trademark “gonorrhea cure” as his best seller. “In one year, we could make a million or more.” Venereal disease was a gold mine, and Chen’s spiraling wealth demonstrated to his relatives, friends and their friends the possibilities of private healthcare. (In 1998, China’s health department sent out a bulletin calling Chen’s acolytes a “gang of swindlers blanketing the country… wantonly scamming money and entrapping patients.”) Chen’s family now owns and operates more than 100 private clinics and hospitals. “As long as there is land,” Chen said, “our Putian people are there running hospitals. I created a new path.”

Chen’s family manages the hospital assets, which include Baijia, a company comprised of 17 maternity and gynecology hospitals. In January 2015, Morgan Stanley Private Equity Asia invested $38 million into Baijia. (Public records show Chen is Baijia’s second largest shareholder; his stake is about equal to that of his nephew’s, Su Jinmo, who is Baijia’s president and chairman.) According to Chen, Baijia is valued at about $308 million. Since Morgan Stanley’s financing, the chain has added on four new hospitals.

Baijia’s practices include linking doctors’ bonus pay to surgery and pharmaceutical quotas—i.e., how much they sell—according to Chen and a gynecologist once recruited to work at a Baijia-owned facility. Baijia’s online “physicians” (actually trained salesmen) detail varying price-point abortion packages—if you’re planning to have a child in the future, they recommend the most expensive option. (Dr. Zhou Dan, a Shenzhen gynecologist who briefly worked at a private clinic with the same pricing scheme, claims they’re all the same surgery.) Baijia hospitals are also unequipped to handle patients who need emergency treatment, and when there are life-threatening complications, according to a manager of a Baijia facility, they transfer patients to local public hospitals.

In 2014, a newborn at a Baijia-owned hospital ingested amniotic fluid during delivery and needed emergency treatment, so the hospital sent the baby to a local public hospital, local news agency Rednet reported. After the newborn died, the hospital spokesperson cited the hospital transfer and declared it impossible to say which hospital was responsible. The hospital then refused to hand over the family’s medical records.

In April 2015, Chinese courts ruled two more Baijia-owned hospitals negligent in the death of one newborn and responsible for inflicting another with cerebral palsy (despite both hospitals transferring the infants to public hospitals at the last minute). In the latter case, the court ruled that Baijia’s Wenzhou Oriental Maternity Hospital had likely falsified medical records and acted to conceal its responsibility. There is additional evidence of a number of similar cases that were settled before trial or never made it to court.

Even when treatment doesn’t end in catastrophe, patients writing on review websites relay being exploited by doctors at Baijia facilities. “Garbage hospital,” posted a patient of the Baijia-owned Maria Hospital in Changsha, Hunan. “A pelvic inflammation cost me more than $1,550 and wasn’t even cured. They simply treat people as ATMs.”

(Nick Footitt, a Morgan Stanley spokesperson, declined to comment. Baijia also declined to comment for this story.)

Morgan Stanley’s private equity arm is helping Baijia expand, Chen Deliang told me, while the company prepares for a public offering. Another American-invested private equity firm, CDH Investments, has already seen a windfall from its investment in a PHIA-member owned hospital chain, which went public on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in July 2015. “I’m pretty satisfied with investments in Putian hospitals,” Wang Hui, a former CDH Investments executive, told China Business News. “In most cases, every hospital starts making money after two to three years of operations.”

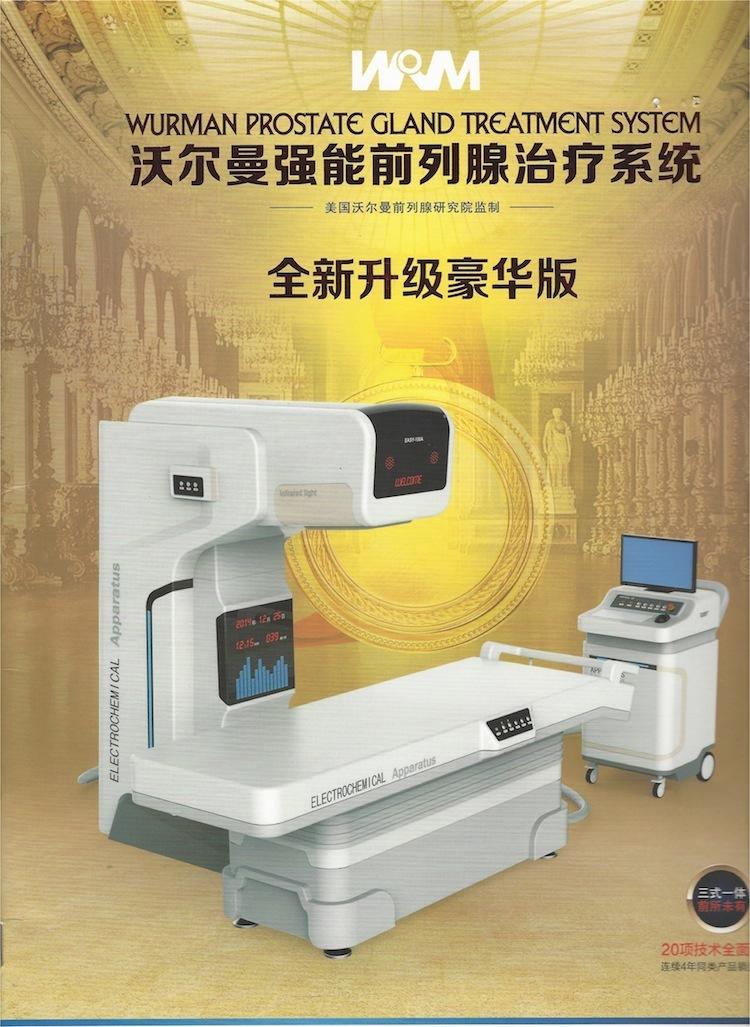

Front cover of the Wolman Prostate Gland treatment system brochure. the English spelling of “Wolman” changes page by page.

Profits from private hospitals have transformed Dong Zhuang from an impoverished farming town into the Beverly Hills of China. The town is home to 35,000 private hospital owners and their employees, about one third of the total population, according to a Dong Zhuang Town official. On plots of land where sweet potatoes once grew, Rolls Royces, Bentleys, and BMWs now park in front of great mansions of glass, onion domes, arches, and parapets. One mansion visible from Chen’s temple window stands 16 stories tall and has more than 100,000 square feet of living space, making it one of the largest homes in the world.

When I visited in February 2015, medical device manufacturers had gathered in Dong Zhuang’s new, three-story exhibition center for an annual medical expo. Lin Jianxing, the organizer, greeted me outside. “Two hundred fifty companies from twenty-eight provinces have come to sell medical devices,” he said. The inaugural exhibition, 13 years earlier, had been held on the street, like a flea market, he explained, but now the exhibition was housed in palatial facilities. “Go on, look at all the equipment in there,” Lin urged me. “It’s really big and advanced.”

A medical fantasyland waited. At the booth of Dekang Medical, I tried on a Sharper Image–type head massager that, the saleslady said, treated schizophrenic voices, depression, OCD, anxiety, mania, and PTSD. A salesman at Dongnan Medical soon explained why many of the devices were built to resemble MRI machines. “Private hospitals need to let customers know these are valuable pieces of equipment,” he said. “The big devices entice customers in for treatment.”

At the table for Zonghen Medical, I marveled at the ZD-2001A Pafeite Shortwave Space Pulse Machine, built with a sleek egg capsule design for patients to squeeze into, which was connected to a control station aesthetically suited to launch a 1960s-era NASA rocket. The device, a cheery attendant said, used shortwave diathermy to produce heat and treat a variety of gynecological and urological diseases. Surprisingly, China Food and Drug Administration has approved the device for medical use, perhaps on the basis of one Chinese study, which appears to have been commissioned by the manufacturer, and claims the machine cured pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in 98 percent of patients without the use of antibiotics. A professor of reproductive epidemiology in the US, however, pointed out that antibiotics and not heat are used for the treatment of PID, as bacteria cause the disease. Studies on using diathermy to treat the pain associated with chronic PID are limited too; one of the few was carried out in the US in 1955, when physicians didn’t fully understand the bacteria associated with PID. This has not stopped Baijia-owned hospitals from stocking the ZD-2001 device and using it to treat PID.

Next, at Shenzhen Yuanda Medical Instrument’s booth, I found what was likely the machine that “treated” Junjun. Advertised as in use on the Shenzhen City Hospital website, I now stared at the “Wolman Prostate Gland Treatment System.” The machine resembled a large, open-style MRI machine, and its sleek white exterior held long English words—”Electrochemical Apparatus,” “Infrared Light.” On the patient table, a framed certificate stated the machine was made by the USA Wolman Prostate Institute, which later research revealed is a dummy company that was registered in Utah in 2011. You Dongqing owns the business, and more than 100 other dummy corporations share the same address in suburban Salt Lake City.

“The red light cures prostatitis,” the salesman said, beaming proudly and handing me a brochure for the Wolman Prostate Gland Treatment System. The brochure featured a photo of the USA Wolman Prostate Institute’s research center, which, thanks to a clearly labeled sign on the building, I quickly discovered was actually a photo of Invesco Field, where the Denver Broncos play football. “Number one seller for four years running,” the brochure read, “in use at 800 private hospitals across the nation.”

The traditional moral compass for physicians—the Hippocratic Oath—has fallen victim to unbridled capitalism and corruption in China, especially in private hospitals.

It was hard to tell, I thought, who was scamming whom. Both the hospital owners buying the machines and the salesmen knew patients like Junjun and Little Huang would trust the advanced, “imported” machines if physicians recommended them. Information asymmetry between doctor and patient is extreme in healthcare. The traditional moral compass for physicians—the Hippocratic Oath—has fallen victim to unbridled capitalism and corruption in China, especially in private hospitals, which saw 11 percent of all visits, totaling 325.6 million, in 2014. Once primarily a trap targeting the young or naïve or uninsured, private hospital chains like Baijia are now moving upmarket and beginning to accept government-run insurance, drawing in new swaths of society as patients. But when false marketing campaigns and supposedly low prices lure people of the middle class, will they too trust the doctor in the white coat and the big machines with English lettering? “The clinic is just a hole waiting for someone to fall into,” Junjun says. “And the health department stamps it with a chop—Legal!”

Mr. Fang, who went to a People’s Armed Police hospital contracted out to PHIA member Wang Wenlong

On the night of November 3, 2015, about a month after Junjun came down off the rooftop in Shenzhen, China’s 21st century eunuchs squeezed into a small guest room on the outskirts of Beijing. Twenty other men joined them, ages 22 to 44, all born in rural areas all over China. For months, the men had communicated through an online chat group, organizing the plans for a protest in Beijing that, they hoped, would finally draw the attention of the country’s highest officials to regulate the private hospitals and find treatment for their surgically imposed erectile dysfunction.

Now, 27-year-old Mr. Li, the moderator of the online chat group who had a dorsal neurectomy five years prior, stood with his legs pushed against the bed. He spoke loudly, so even the men packed into the bathroom could hear. Junjun was pressed into one wall, shorter than most, and he craned to see Mr. Li.

“We’ve got our petition,” Mr. Li said, raising a 31-page document that Junjun had handwritten the previous day. The front page held each man’s name, hospital, and thumbprint, and inside pages included detailed narratives about each man’s injuries and attempts to seek redress. They planned to deliver it to the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) office, the Communist Party of China’s top organ for rooting out corruption and malfeasance, at 8 AM the next morning.

If the men succeeded, they hoped the Communist Party officials would be moved to action by the stories detailed in the petition: That of 24-year-old Mr. Xi, who now sat cross-legged on the rock-hard bed, with a scar on his wrist from where he slashed it while pleading for help in his local health commission. There was the story of nearby Mr. Yao, whose wife had divorced him after a dorsal neurectomy left him impotent—he’d subsequently climbed to the roof of his local health commission to douse himself in oil and threaten to light a match. And then there was Mr. Gao, a lithe 25-year-old who was now, despite the crowded quarters, sprawled in the center of the bed, his face flushed red from alcohol. He’d cut off his own pinkie finger while pleading for justice, and now he used his four-and-a-half fingered hand to wave his phone at the group.

On the phone’s screen, Junjun and the others saw text messages from Mr. Duan, head of Mr. Gao’s local health commission. Mr. Duan had followed Mr. Gao to Beijing to beg him not to participate in the protest, out of fear that the men would successfully attract the attention of high-level Communist officials. “Come home with us tomorrow, and we’ll resolve this,” Mr. Duan had written. “No matter what you do, in the end, you’ll have to return [home] for a resolution.” In another message, Mr. Duan had offered $7,730 if Mr. Gao left Beijing.

“We’ve got to last at least a couple of hours,” Mr. Gao said, confidently. His own protest back home in Shanxi, on the roof of the private hospital, had lasted at least as long and earned him his first audience with Mr. Duan.

“Even if the People’s Armed Police rope off the area,” offered Mr. Wang from Shenzhen. “We’re not leaving.”

“They’ll drag us away,” added another man.

“We’re not breaking any laws,” Mr. Wang shouted. “Breaking the laws? They destroyed our cocks!”

The next morning, after a fitful night’s rest in the guesthouse, the men awoke to find thick smog choking Beijing. They had not scouted the entrance to the CCDI building, and they were dismayed to discover that a blast wall, towering 20 feet tall in stretches, rings the complex. At the main gate on Pinganli Boulevard, an officer stood on a podium, with a detachment of five more standing in a roped-off cordon at his feet. Still more officers filled two public busses parked to the left and right of the entrance.

The 24 men crossed the wide boulevard and gathered opposite the gate, where only a couple of officers sat in two police vans.

On the sidewalk, the men broke into two rows. Little Huang dropped his backpack and pulled out a banner reading, “National Dorsal Neurectomy Victims.” Another man to his right held up, “Evil Hospitals Scam Money and Murder.” Junjun dropped to his knees, as did other patients in the front. As the banners went up, the men chanted, “Evil men’s hospitals, return my well-being!”

In the end, all of the protesters would spend five days in detention before being released into the custody of their local government officials, who promptly deported most of the men back to the countryside. Little Huang recently received a small settlement from his clinic. Junjun is in the process of suing Shenzhen City Hospital. The clinic, however, has received no penalties or fines, and the closed surgical room has reopened.

But on that morning in November, they still had hope. Had there been an official walking into work at the very moment the men started their chant, he or she may have turned to see what the commotion was about. He or she may have seen the banners, may even have crossed the street to take a copy of Junjun’s petition. Maybe he or she would’ve read it, too, understood the men’s suffering, and as all 24 (and hundreds more too scared to come to Beijing) dreamed, launched a project to find a cure.

Instead, in less than a minute, a large police van flashed out from a side street and pulled to a stop in front of the protesters, screening them from view. First to go were the banners—officers tore and stamped them to the ground. Scuffles broke out. More police vans arrived; the first group of men was carted off, then the next. In ten minutes’ time, there was no sign of the protest or the banners or the eunuchs.

* The names of victims have been changed to protect their identities.

**Lin Zhicheng recently transferred his stake to another Putian man, but his name remains on the building lease.

Follow R.W. McMorrow on Twitter.

This article appeared in the May issue of VICE magazine. Click HERE to subscribe.