A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

As a writer, I know a lot of other writers, and I hear a common refrain among the writerly set—they have billions of tabs open, each with a potential new thing to read that they hope to get to someday, but might not ever see.

Videos by VICE

The tabs bleed into one other, their icons shrinking in width and slowly becoming unclickable.

I should be that person. I’m not. Maybe I’m weird, but I’ve somehow managed to become a tab minimalist, and I think you should, too.

Here’s why you should close your tabs without regret.

In defense of closing tabs every chance you get

This week, a writer from Slate named Rachel Withers made the case that you should let your tabs just keep piling up, there forever, filling your browser and your life with a never-ending stream of information that maybe, just maybe, you’ll get to someday.

She evokes a concept called “tsundoku,” or the Japanese idea of letting books pile up even though you have plenty of things to already read, and creates a separate but related term for the web browser version of it: Tab-sundoku.

“Some suggest academics are especially prone to tsundoku—I would suggest digital journalists might be more prone to tab-sundoku,” she writes. “Excessive tabs show, more than anything, a deep curiosity, a thirst for knowledge.”

(You can be thirsty for knowledge without drinking every glass put in front of you, right?)

She also, preemptively, comes up with arguments against folks who have figured out how to keep their tabs manageable.

“All this smug advice over tabs is not unlike the Cult of Inbox Zero, which declares that keeping your inbox at zero emails is the only way to live,” she suggests.

I personally don’t subscribe to Inbox Zero, and I certainly would never tell anyone how to let their inbox grow. (Let those old Huffington Post news emails grow like ivy around your ever growing amount of Gmail space!)

And I don’t want to be smug or condescending in my arguments for fewer tabs, so let me be pragmatic: Tabs stress me out.

They’re the digital equivalent of a never-ending sheet of bubble wrap, with new options for popping just hanging out there, begging to be turned into a new target for my popping fingers.

All that popping is fun, of course, but at some point, though, it gets in the way of the things you’re actually trying to do—in my case, write. (If you’ve ever played Universal Paperclips, it’s the same concept. Sorry, I just made you open up a tab.)

We’ve come a long way from 1994, when AOL paid $30 million for BookLink Technologies, widely believed to be the first company that made a web browser that implemented multithreading, the secret sauce that makes all that tabbing work.

And we’ve seen a lot of innovations since then—Opera, and then Firefox, popularized tabbed browsing in the early 2000s, while Chrome’s contribution was the all-important Pin Tab feature.

But the biggest thing that’s changed is the sheer number of options. The internet is full of impressive ways to waste your time. A browser bar full of tabs is a constant reminder that something new is just around the corner.

Lots of new things are great, but everyone gets sick of ice cream after a while, right? It’s for this reason I find TV best in small doses, and I don’t watch it at all if I’m trying to be productive.

Keeping a lot of new tabs open is the information equivalent of scheduling 15 doctor’s appointments in a single week. There’s no way you’re going to make all of them, and you’re going to drive yourself nuts trying.

So, don’t try. Cancel some of those appointments. Close some tabs.

Five ways to help ease your tab addiction

-

Make closing tabs the second easiest thing you do on your computer. The easiest thing to do on your computer is probably scrolling down a web page with your laptop’s trackpad, right? Fortunately, there are lots of tools that allow the creation of gestures that are just as simple. I personally used a piece of software for the Mac called BetterTouchTool (available as part of the Mac subscription service SetApp) to create a simple three-finger scroll-down gesture that closes the tab. The less friction, the better.

-

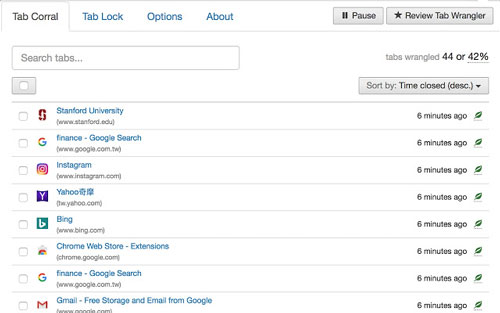

Automate the closing of tabs. For years, I’ve used a tool called Tab Wrangler to basically play garbage man for my habit of leaving tabs open. It’s like a Roomba for your browser. This is not a tab management tool, like OneTab. No, it’s a tab excavator, a strip miner of tab-based minerals. With a few exceptions, such as currently playing YouTube videos and websites I’ve specifically told it to ignore, Tab Wrangler automatically closes any unpinned tab after 10 minutes. If that seems a little aggressive, you can always increase the time, but you don’t have to, because …

-

Your browser’s history is searchable. Did you know that there’s an existing tool that automatically catalogues everything you’ve viewed on your browser, and it’s searchable, too? Instead of feeling nervous that you missed something because you let a tab close, feel confident that you will be able to rediscover it using your browser history. Heck, omnibar-based browser setups, like Chrome and Opera, also remember the tabs you opened, so you can save some time. Thanks to the omnibar, I don’t even use browser bookmarks on a regular basis.

-

Pin the tabs you really care about. Most modern browsers have a way to keep tabs you really like there for you at any given moment, and that feature, the pin feature, is simple but powerful. That Slack channel you like lurking in can go there, along with that long PDF you’re digging into. By giving priority to the tabs you really, genuinely care about, you’re ensuring that there’s never too much spare bubble wrap lying around.

-

Use a social bookmarking service. Tools like Pocket, Pinterest, and Refind are great for making sure that whatever you’re reading will have a paper trail that’s connected via the cloud, and that links you care enough to leave behind are there for you when necessary. Another great tool of this nature is PushBullet, which I use as a way to send interesting links from my phone to my browser. Again, if you like saving stuff for later, minimize the friction by using a trackpad gesture or a simple-to-remember keyboard shortcut. And integrate it in your routine. The easier it is, the more likely you’ll do it. And the problem with closing tabs is often a lack of motivation to do so.

Embrace everything in moderation, including tabs

Now, don’t get me wrong. I realize that there are a lot of folks who will find this approach to tabbing scary and nerve-wracking. And my argument may not assuage your concerns about the place that tabs deserve in your world, and in your life.

Maybe you feel like you’re missing something by leaving them open. Maybe you feel like you must have your fingers shoved into parts of of every single book, with the information always there, ready for you whenever you’re ready to get going again.

Perhaps I won’t convince you otherwise, because you’re nerve-wracked by tabs that aren’t there when they should be. Fine. Have it your way. (This blog post is the equivalent of Web Browser Burger King.)

But we live in a world where information is everywhere, of differing quality, and of differing importance. It may be a more prevalent resource than even the air we breathe or the water we drink, because there’s so much of it, and finding more is incredibly easy.

Maybe too easy.

To go back to Rachel Withers’ tsundoku example, I’d like to argue that tabs are different from books. Unless you’re a masterful speed-reader or you like to sit for long periods of time, you’re not going to plow through a 400-page book in a single sitting. And that’s OK. We consume at our own speeds.

But when the information becomes structured in a way that you have to do almost nothing to dive into a new piece, where information is easier to consume than a bowl full of miniature Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups, the consumption habits lean precariously toward information overload. And the structure of there being always something else to read creates unwanted guilt.

This isn’t the same as Inbox Zero—where information is being shoved into a box we’ve set aside for that purpose, and we’re expected to read it. A pool of unrelated tabs sitting around for a month is entirely of our making.

I’m a human being that consumes a lot of information on a given day, someone who can turn a wild goose chase into a structured work. I’m aware that the next important detail might be hiding behind the next tab, like the world’s smallest needle in the world’s largest haystack.

But by keeping every tab open, I let the haystack win because I give every piece of information the same amount of value.

A minimal tab experience is a great way of saying to oneself that the piece of information you’re reading is worthy of your time. It’s not a judgment on the value of anything else—but by keeping all the other tabs at bay, you give your brain a little more room to embrace the piece of information in front of you.

Sometimes that extra space is the difference between a finding a needle and getting weighed down in hay.

None of us are perfect, however, and this piece I think gives me the perfect opportunity to draw attention to an example where the tab system breaks down for me: Within the many applications of Adobe’s Creative Cloud suite.

The problem is this: On top of all the other problems with keeping tabs open, Adobe adds the extra wrinkle of requiring folks to save something, perhaps before it’s ready. This is maddening, though it’s not unique. Some text editors, like TextMate, also put up this roadblock, while others, like Bear or Evernote, make a point of not letting such a roadblock ruin your experience. (Mobile apps generally make a point of not creating a roadblock like this.)

As I trumpet the need to close tabs in their web browser, my inability to save things that I’m working on in a photo-editing application is my Achilles’ heel. I often find myself stuck with photos that I edited weeks ago, sitting there just because I haven’t spent the time closing them because I know that closing them means saving, and saving means time that I don’t want to spend.

This is particularly painful when I need to restart my laptop, and I’m prevented from doing so by the 36 images, in various stages of creation, sitting there expecting me to save them. I can program a macro to not save things I don’t want to save, but I sometimes wonder if the problem isn’t me, but Photoshop or InDesign. Maybe these applications need to be built with a history tool not unlike a web browser, so the process of creation can be picked up later—because this is how people actually create.

To the creators of Tab Wrangler: I have an idea for your next project.

More

From VICE

-

Collage by VICE -

Collage by VICE -

Collage by VICE -

(Photo by Tom Kelley/Getty Images)