The unexpected end of Plastic People this month rounded off an annus horribilis for nightclubs in the UK. In London, the club closures were too many to list. The city’s LGBT clubbing scene was hit particularly hard with the loss of both Madame Jojo’s and Joiners’ Arms. Outside of the capital, Liverpool’s legendary Cream and independent club The Kazimier suffered a scare after being earmarked for demolition by local planning officials. Across the country, late night levies continued to be rolled out in city centres, forcing nightclubs to close early to avoid additional costs.

All of which begs the question, what can we do to reverse this decline? Every time a nightclub came under threat last year, thousands rallied behind it online. When news broke that Fabric’s license was being reviewed in November, a petition backing the club gathered 30,000 signatures overnight. Despite the outpouring of support, Islington council imposed stricter security conditions on the club including drug dogs and ID scans. “It’s not a level playing field in there,” complained Fabric owner Keith Reilly, to one of the councillors after the meeting. Reilly’s frustration is understandable: outnumbered by disgruntled residents and a large police contingent, the room felt decidedly against Fabric.

Videos by VICE

Clubbers are given almost no say in the governance of nightlife. Decisions over clubs are made behind closed doors and even local councils are, on occasion, passed over altogether. When a developer proposed to build a block of flats opposite Ministry of Sound in 2012, London mayor Boris Johnson intervened. Speaking at a city hall meeting called to resolve the dispute back in November 2013, Johnson shared an anecdote about having once “strutted my funky stuff with Ulrika Jonsson” at the club. Perhaps that magical night on the tiles was enough to sway him, as a month later the application was approved on the condition the flats will be soundproofed.

While Ministry might have come away victorious, the intervention raised more issues regarding transparency. Neither has the outcome set a precedent for similar cases. Smaller clubs, such as Egg in King’s Cross, have not been able to secure the same guarantees, even with a residential development just a stone’s throw from their doors. Only clubs with the considerable resources to fight their ground it seems can co-exist with “regeneration” schemes.

Across the Channel, two cities might provide the answer to our current predicament. In Amsterdam, Mirik Milan currently holds the post of nachtburgemeester [“night mayor” in Dutch]. The voluntary, unpaid position was created in 2003 by the city council. Milan, elected in 2013, is the fifth mayor. As the title suggests, the night mayor serves as a spokesperson for Amsterdam’s nightlife. “I advise the mayor on rules and regulations for bars and clubs because while [the government] know what’s going on in the city in general they have no clue what is happening at night,” says Milan. One of his proudest achievements thus far has been to been to secure 24 hour licenses for ten clubs including Trouw, Overkant and Westerpark.

Although the post is officially sanctioned, Milan is nevertheless handicapped by a lack of powers, reliant on influencing the policymaking of his daytime counterpart. Thankfully, the current mayor proper, Eberhard van der Laan, has been largely supportive. Over in Paris, however, night mayor Clément Léon doesn’t have the recognition of the city government. Léon, who was elected in an online poll in 2013, was cautiously optimistic about the possibility of working with Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo after she listed the appointment of a nightlife representative in her election manifesto. Since Hidalgo assumed office in 2014, however, he’s found himself sidelined. “She doesn’t support me. If I want to be heard I have to do it through protests and boycotts,” he says.

Even in Amsterdam there are no assurances of support from successive governments. Both Léon and Milan are adamant they are prepared to work with any mayor regardless of political affiliation. “We’ve come from the nightlife so we’re not politicians, not yet at least,” says Milan. Nonetheless, Milan has had to make some concessions to the current administration. He mentions the idea of regulating illegal raves with “a non-commercial rave permit” which limits the number of attendants to 300 and prohibits online promotion. By Milan’s own admission those conditions are there to protect businesses – from unwanted competition – and cede more control over nightlife to the police, further restricting the clubbing landscape.

One alternative to the mayoral model might be for nightclubs to represent themselves. In Berlin, the Clubbing Commission brings together 125 club owners and promoters. “When individual clubs have tried to raise concerns to the government they’ve been told that ‘We don’t talk to individuals, we only talk to organisations’. So we organised ourselves,” says Lutz Leichsenring, who heads the commission’s board.

Much like London, rising property prices are transforming Berlin and forcing clubs out of the centre. Over twenty clubs have closed in the past five years with the Commission predicting many more in the future. The Germans even have a word for the phenomenon, clubsterben [literally, “club death”]. “In some respects it’s like putting out fires, attempting to save a club when it’s already too late” says Leichsenring. “The only way we can change things is by convincing local planning officials that the death of more clubs would be detrimental to tourism.”

Although many clubs remain at risk, Berlin’s government have at least been willing to support the underground music scene with a €1.5 million (£1.2m) annual fund – overall, the city spends close to a billion on arts according to Der Spiegel. While there is no direct equivalent in the UK, London was allocated £209 million by the Arts Council in 2013-2014, with two-thirds of music grants going towards opera and classical – a very small proportion was awarded to dance music related projects. Katja Lucker, the director of Musicboard, the organisation which oversees the fund explains that “We’re not supporting the bigger clubs directly so we wouldn’t give money to places like Berghain or Watergate. Mostly what we are doing is supporting events that take place in smaller clubs.” By focusing on individual events and artists, Musicboard avoids funnelling public money to privately owned nightclubs while still contributing to the city’s thriving dance music scene.

There are, however, limitations to what can be achieved with the fund. For one, it doesn’t address the much wider impact of gentrification, and with it, the sanitisation of nightlife. “It is a lot for one organisation to deal with,” admits Lucker. “We’re trying to show the value of dance music culture to the city, both its inhabitants and its government. It’s not only theatre and opera houses that are important to cultural life.”

Back in the UK, clubbing and dance music have historically been treated as a public nuisance rather than a culture. It’s telling that the closest equivalent we have to a representative for nightclubs is The Association of Licensed Multiple Retailers, an organisation that groups them together with bars, pubs and restaurants as another revenue stream for the alcohol industry. Out of the ALMR’s 175 members, less than 10% are clubs and only a handful are independent. Notable omissions include: The Warehouse Project, Sub Club, Thekla, Dance Tunnel, The Bussey Building and Sankeys to name but a few.

The clubs that the ALMR does represent are largely high street chains like Oceana, Liquid, and Tiger Tiger. Novus Leisure, who manage the latter and sit on the ALMR board, are unashamed about their ambitions for attracting a very specific clientele. “I think the cocky confidence of the City is coming out again. The City is being a bit reborn and we wanted… [to] capture that feeling,” a Novus spokesman told the The Evening Standard last year.

Part of the difficulty with organising nightclubs is they are in direct competition with each other. Corporations like Novus, and Luminar (who manage Oceana and Liquid) are seeking to aggressively expand and monopolise town centres hastening the demise of the independents. Justin Berkmann, who co-founded Ministry of Sound, suggests that cooperation is unlikely. “They tend to not get on with each other even at the best times, not hostile but certainly not friendly with each other. So I think it’d be interesting to get all of those people into one room and see how much blood would end up on the ground afterwards.”

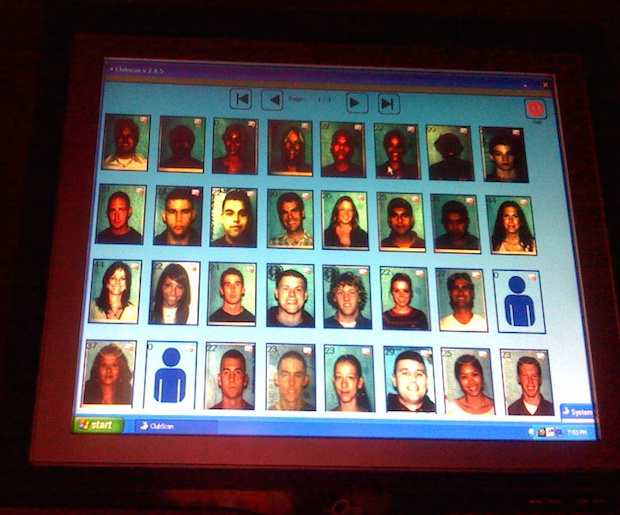

A greater concern over groups like ALMR is whether they represent the interests of clubbers. Of late, a growing number of clubs have been adopting invasive security measures such ID and fingerprint scanning and even breathalyzer tests. While it is often the case that these are imposed on clubs by council licensing boards and police, many have adopted the technology of their own accord. According to IDScan Biometrics, the market leading providers of ID scanners, over 5,000 machines are already in operation. While the ALMR has stopped short of advocating such practices, tellingly their objections have been over the potential outlay rather than any concerns over infringements of privacy. Would a coalition of nightclubs would be willing to check this trend? It seems unlikely.

Club-goers are not the only group with a stake in nightlife, the industry’s workers have also long been denied a voice. They might further suffer as a result of nightclubs concentrating their power into a single body. In the past, the ALMR has lobbied against wage increases with Nicholls having pledged to “campaign to prevent potentially harmful rises in the minimum wage”. Nicholls, however, denies that this is the ALMR’s policy: “When we’re taking about employment costs it’s not the amount that we’re paying out to our staff and actually nightclubs are one of the better paying sectors within the hospitality industry they pay well above the minimum wage.” Research conducted last year suggests otherwise, with 90% of bar staff having been paid less than the living wage, the highest proportion of any occupation, according to research carried out by KPMG. The average hourly wage was a lot less, £6.57 – just 7p above the current minimum wage.

It seems fair that both clubbers, and those employed by nightclubs, should have some say in how nightlife is governed and regulated. That, of course, has not been the case in the UK and it remains to be seen how those groups might be empowered. None of the organisations and representatives I spoke to seemed to offer an entirely satisfactory model for how nightclubs can be run to best serve the needs of club-goers, artists and workers. Equally, few seemed to have concrete solutions to the deeply-rooted problems forcing so many clubs to close across Europe – especially in cities like London and Berlin, currently being transformed by housing bubbles.

Although it’s understandable to want to preserve as many of a city’s nightclubs as possible, stasis can be almost as suffocating to a culture as the loss of a long-standing venue. As one of the founders of Liverpool’s The Kazimier’s told me: “I don’t think clubs should stay open forever, I think its exciting that clubs have a beginning, middle and end. What we do want is some control over our destiny.”

What should be of more concern is the restrictions that are inhibiting a scene from building anew. If closures themselves have taught us anything, it’s that they can inspire hugely popular grassroots campaigns. Much could be achieved if that energy was redirected towards many of the battles dance music culture faces as a whole. In 2015, the commodification of dance music continues apace with the growth of a billion dollar EDM industry, clubs marketed towards an affluent minority and DJ Mag polls that resemble Forbes’ rich lists. All while women, persons of colour and the LGBT community are struggling against barriers to participation. In focusing on individual losses, we risk overlooking the entrenched problems that are leading to the standardisation, segregation and privatisation of the scene at large. While we need not mourn nightclubs, the need to fight for our right to party is evermore urgent.