Commandos 2 has two mouse pointers. One contextual, to change appearance over manipulable parts of the environment or coast over opened interface screens. The second pointer is attached to the first to function, essentially, as its minder. As you waggle the one over prerendered bunkers and into trenches, the other remains outside, trammeled to what’s actually within immediate reach of the soldiers you control, to the tangible surfaces. “He won’t be but a minute” the pointer might say, leaning against the pock-marked wall of some Bavarian castle, cigarette in hand, waiting for whenever its partner returns from your flights of fancy. Or so I imagine.

But mouse over to anything on the periphery, and the capricious pointer comes back on a different side and some new distance apart from the anchoring one. And so suddenly there are new concerns overlayed across the game’s fictional matters of stealth and subterfuge: Where do I have to click on something to actually click it now? And how long must I compensate for this new discrepancy, until it changes again? The interface will throw these switch-ups at you at inopportune times: when you’re trying to duck one of your commandos just out of a Nazi’s sight, or fumbling to have them pick up a ticking time bomb. Thusly they die, and you lose—too often.

Videos by VICE

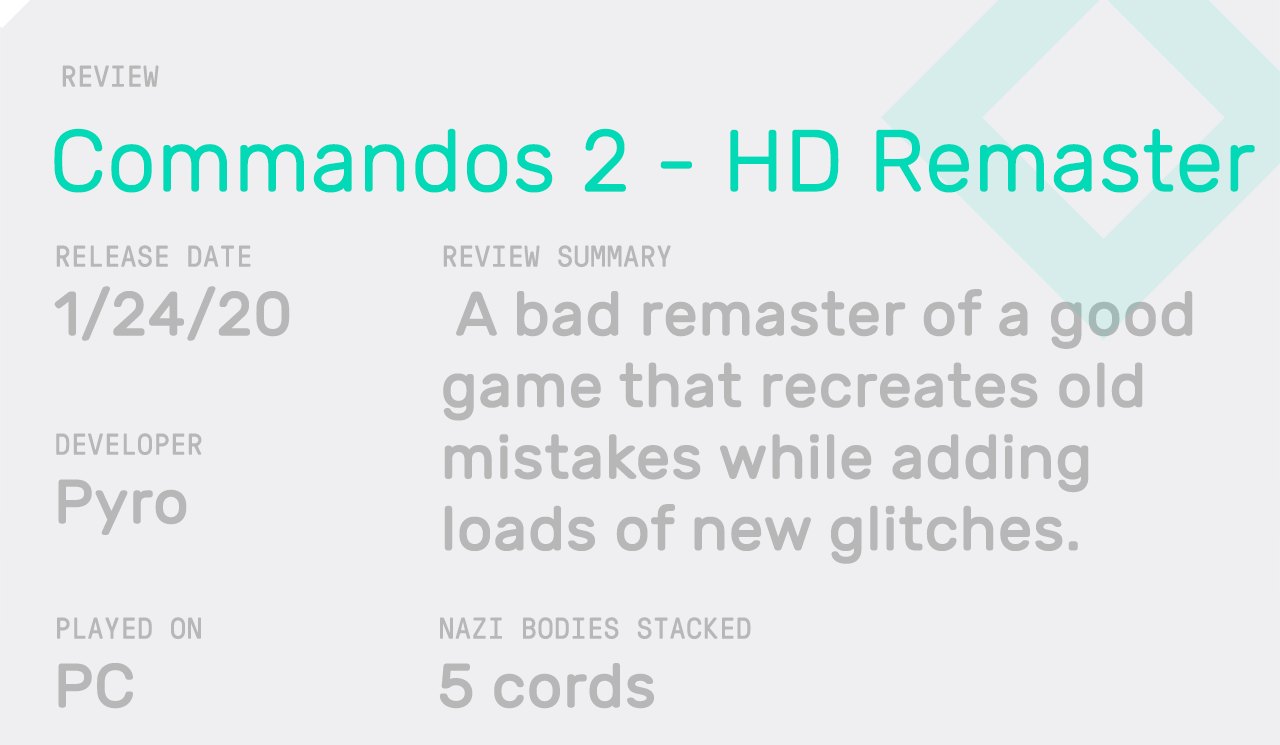

If this sounded like too egregious a problem to let stand, well…perhaps by the time you are reading this review it’ll have already been remedied, and all that lavish metaphor up above will be null and void. This is ostensibly a problem for the critic. A game is released, poorly; it suffers the slings and arrows of a few thousand users on Metacritic or Steam and the reticent journalists’ “reviews-in-progress” (cowards), and the publisher promises a battery of quick patches.

Maybe it delivers. And then what do you do? Your first experience is indelible, all glitches and frustrations, but you’re expected to form some conclusions that will stand up in posterity against a product that might look wholly different in a matter of months. Or even weeks. Days!

I seem to recall someone recently quoted in one as having said that a video game is basically a series of problems. If that’s the case, then bugs and glitches may—to be a bit deliberately obtuse about it—just be another problem for the player to solve, another dash of friction. To the puzzle-solver this is a difference not in kind, but in mien, like what strictly, biblically differentiates an angel from a demon.

This remaster of Commandos 2 is, or was at the time of my playing, full of such “problems” to solve. Textures flicker in and out of existence. Audio drops out every 3rd or 4th time that I reloaded a save (fixed now, I gather). Beginning with Mission 2, my commandos stopped being able to descend interior ladders en masse; I was forced to develop a workaround where I’d allow their grip strength to fail and then just drop them from the top rung. At one point, jumping back into an arctic level, all the parkas given to my characters began simply disappearing—sometimes when they fired a weapon, sometimes just because—and so suddenly my mission became an impromptu race against time: defeat the Nazis with my new crack team of Boys Who Wear Shorts All Winter, before they all freeze to death.

Each new issue sent me desperately beachcombing through old forums and FAQs (bless this one in particular). It put me in mind of that xkcd comic about the “wisdom of the ancients.” Often the bug was new, or at least, undocumented. But these archival dives showed that a healthy portion of the problems were old, known commodities. The inadequate instructions, the exploitable action-cancelling, the overpowered-to-the-point-of-being broken Guard mode…to hear them described by users in the early aughts, you could almost conflate them with features. Even one instance where a cutscene wouldn’t trigger, causing a main objective to remain inoperable, turned out to only be the result of an abstruse conditional, reproduced two decades later. “Try giving the enigma machine to Natasha and letting her operate the radio,” was the sage advice of the old sherpa guides, and it worked.

Attuning myself once again to the rhythm of puzzle solving, I started to register this all as merely additional criteria, the kind that speedrunners and completionists impose on themselves on a lark. Or like the bonus objectives in 2016’s Shadow Tactics: Blades of the Shogun (a game very much in the Commandos tradition) which a guest on a podcast I was on summarized well: “This level is designed to train you to use this character’s skill…Don’t use that skill.”

But there’s a certain nostalgia in a game as particular as this. In that indifferent, inscrutable human engineering, the kind you find in adventure games from the same era: this character must use this object on that one, in this specific order, for reasons that are simply, impenetrably, encoded. Like If/Then statements preserved in amber.

There’s an element original to the 2001 release which I am a bit surprised they didn’t take the opportunity to revisit: the material surrounding Natasha, the game’s sole female character. Here’s how Commandos 2’s manual describes her role: “Exploit Natasha’s natural charms…Dressed in sexy clothes and using her lipstick she can distract enemy soldiers so that her comrades can avoid detection.” The accompanying illustration shows her in a negligee (even though her character model is always clothed) with one strap loose.

A bit of background. Each character in Commandos 2 represents a class archetype. Sniper, for example, or Driver, or Thief, though frustratingly, it insists on referring to them obliquely by code names, like “Inferno” or “Duke,” without ever connecting those names to their faces. When characters are notable only for the utilitarian roles they play, best to be direct, I think; Monaco: What’s Yours Is Mine had it right when it labeled its pickpocket, simply, “The Pickpocket.” But even that game had “The Redhead,” whose primary and unique ability was attracting enemies.

Homage often seems to take precedence over good sense, so it’s not surprising that Shadow Tactics replicated this role as well, if a bit more sensitive in the execution (Aiko, the “temptress” character there, is arguably the most competent and complex of the game’s characters). But the ubiquity is the thing here, and Commandos 2’s portrayal is about as bad as I’ve seen it. If the game can recompose its character portraits, I expect it could at least address the garish (and unrepresentative) manual illustration, and perhaps its text. We can get into a debate here about the relative purviews of “remastering” vis-à-vis “remaking,” but as it turns out, the game has already made some heavier-handed updates.

Much has already been made about the removal of Nazi and Imerial Japanese iconography from Commandos 2, especially in those Metacritic and Steam user comment sections. That publisher Kalypso opted to roll out to the world a singular version of the game that complies with German censorship laws regarding “incitement to hatred,” seems to say as much or more about the game’s rushed and cut-rate development as it does about freedom of speech concerns. As Tim Stone points out over at RPS, Kalypso’s internal policy seems to be implemented somewhat selectively, anyway.

Contrary to the cringey treatment of Natasha that I wouldn’t mind seeing excised, here the removal is of historical references that simply classify that which is already portrayed. There’s no mistaking the soldiers in their black jackboots, carrying their MP40s, driving their Kubelwagens. Scrubbing out the swastikas and the rising suns (and Hitler from the original introductory cutscene) robs from the game’s enemies some sense of intentionality, and I imagine that meets something of the spirit of the law in question. And yet nothing about their inclusion could possibly be construed as positive connotation—the only things to be done with a Nazi here is to avoid him, distract him, knock him out, drug him, shoot him, blow him up, run him over…the solutions to your various Nazi problems s are pleasantly open-ended.

Shadow Tactics was my first blush with this microgenre. Both games feel, to me, to be about the imposition of order on these collections of variables, gradually reducing their number with a swift punch or a bullet, sweeping them off the board and into a bin or a body of water. Rob described it as “trying to change the workings of a kinetic sculpture,” which sounds apt, if a bit more highbrow than the primal way I play them. Both games seem to always find me compulsively piling bodies in far-off corners, like a dog burying bones.

Shadow Tactics refined and synergized most of the best aspects of the Commandos and Desperados series, like the latter’s ability to bank the actions of multiple characters perform them simultaneously. A few other changes that could be called “quality of life” adjustments make for a game that’s much easier to parse at a glance, like the use of toon shading and generous environmental highlighting. It didn’t have interiors, though the wasted minutes I’ve spent trying to click on objects stuck behind walls on all four of Commandos 2’s axonometric cameras have tempered my enthusiasm for them ( somehow both mouse pointers are out of their element indoors).

In the face of the genre’s ergonomic evolution, and coming long after the original games’ own worthy descendants, this remaster risked calling attention to the datedness of Commandos 2’s approach, not just its presentation. Shadow Tactics is sharper, slicker, more finely attenuated and readable…and yet I find Commandos 2 more open-ended. Chalk it up to less signposting, and to having more tools at hand (the inventory is an embarrassment of riches: full of bombs and poisons and decoys). It’s easy to insert yourself right into the middle of its big, glass-box levels, ensconced between the sight cones of all the soldiers going about their patterns, generously pantomiming the motions of war.

That open-endedness, I suspect, is what left room for the bugs in the original game (I have to imagine that strategy game design is about reducing variables as playing the games is, and more). For the remaster, though, it’s a poor excuse, and I don’t expect anyone who played the original game to find its old idiosyncrasies as quaint as I do. To say nothing of the new bugs, for however long they persist.

Not for the prospect of some better textures, at any rate. Even the remodeled, more bobblehead-like character portraits are unpleasant—eyes rolling around in their heads, mouths working like they’re chewing cud, really barking their combat barks—and hardly qualify as an improvement. With little to say for the additions, I imagine it’s easier to focus on what’s been taken away.

As a late-comer to the series (and by no means a stickler for the details of war) the censored iconography didn’t weigh heavily on me while I was playing. But then, isn’t that comfortable ambivalence exactly the problem? A game candidly set in World War 2 should, at least, contain something of the friction that combating the Axis powers by name entails. A small lesson, imparted for the low, low cost of a few dozen reloaded saves and trips to the FAQs: History without at least a little discomfort is missing part of the story.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Matt Vatankhah -

Screenshot: Activision -

Screenshot: Blizzard Entertainment -

Screenshot: Robin Entertainment