It would’ve sounded like a a discussion of Quranic terms to an outsider. Or at least that’s what Yudi Widiana Adia and Muhammad Kurniawan appeared to hope. The two men, one a lawmaker with the Islamist Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) and the other a member of the city council in Bekasi, West Java, were allegedly discussing the terms of a kickback from a roads project in Maluku.

Kurniawan was allegedly acting as a middleman in the graft scandal, offering to deliver a “commitment fee” from the construction firm PT Cahaya Mas Perkasa to Yudi, who was serving in the House of Representatives’ (DPR) public works commission at the time. Anti-graft investigators accused the commission of routinely demanding a percentage of government roads and infrastructure projects as a kickback to approve tenders. The illegal fees, which were worth millions, often skimmed off 7-8 percent of a project’s total cost.

Videos by VICE

So when the KPK agents saw Yudi talking using Arabic words like liqo (a meeting) and juz (parts) they knew what he was taking about. The PKS politician allegedly told Kurniawan he wanted “around four juz mixed,” in a text message exchange or, according to the KPK’s reading of the conversation, “around Rp 4 billion ($300,187 USD) in rupiah and US dollars.”

Here’s how the conversation (allegedly) went:

“Last night, I had a liqo with ‘ASP’”

“Yes, how any juz?”

“Around four juz mixed.”

It’s not the most complex code to crack. But Indonesia has a long history of talking in code when discussing some rather illegal corruption business. Gen. Suharto’s New Order regime centralized corruption under one roof, effectively turning corruption, collusion, and nepotism (KKN) into an industry itself. Corruption was so bad during Suharto’s era, that Transparency International named him the world’s worst kleptocrat, estimating that he had amassed a fortune of $35 billion USD (Rp 466.4 trillion) by the end of his 32-year reign.

But after Suharto’s fall KKN became anyone’s business. Transparency International ranks Indonesia as a seriously corrupt place, ranking 90 out of 176 countries behind India, Malaysia, and China. The country’s anti-graft body (KPK) has taken down countless corrupt politicians, police, and businessmen in so many high profile graft scandals that it can be hard to keep track. So it’s no surprise that the country’s widespread corruption would spawn a language of its own.

“I think that’s a way to avoid leaving a trace and evidence, especially since the KPK has the authority to conduct a wiretap” said Adnan Topan, a coordinator with the non-profit watchdog Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW). “So when they communicate with one another, they use terms that have the lease to do with their main purpose.”

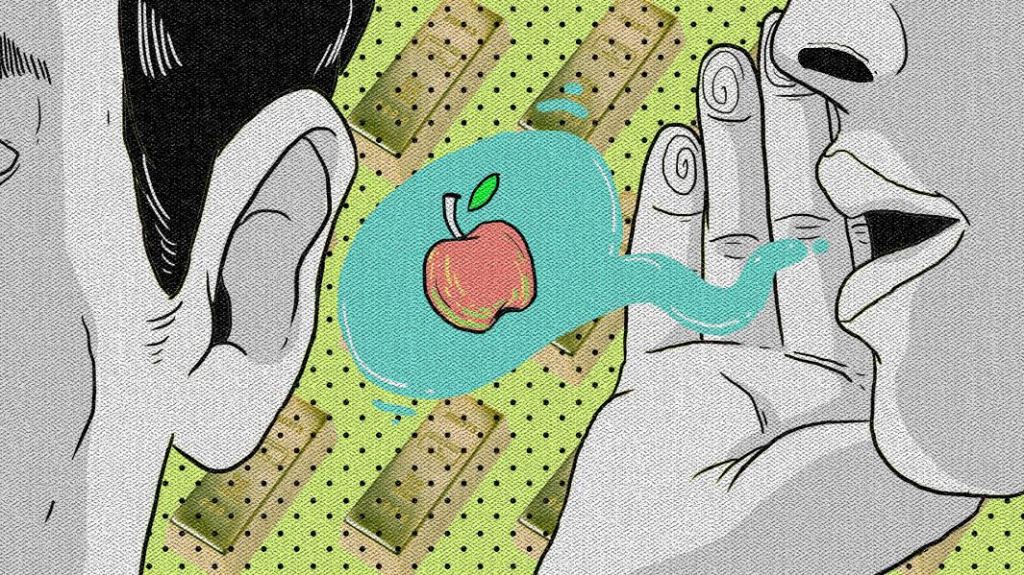

Terms like what? Fruits, children’s snacks, Arabic, kinds of coffee, the names of pop stars, traditional foods, Islamic terms, the list goes on.

“It takes a lot of work and skill from law enforcement to crack these codes,” Adnan told VICE Indonesia. “That’s why most surveillance ends with investigators catching them red-handed, because otherwise it’s difficult to charge them with bribery.”

So what are some of the most well-known corruption code words in Indonesia? We’re glad you asked.

Apples

There are only two kinds of apples that matter according to Mindo Rosalina Manulang and Angelina Sondakh: Washington Apples and Malang Apples.

“Washington apples right? But only 1 kilogram because I’m running out of stock…” Rosa said.

“OK, but don’t forget the rest in Malang apples,” Angie responded.

They were, of course, talking about US dollars (Washington) and Indonesian rupiah (Malang). But the code goes on. Rosa was known as “penyanyi” (singer) because she shared her name with a popular Indonesian singer named Rossa Roslaina Sri Handayani or Rossa. A request for more money was “semangka” or “watermelon” and all bribes were “pelumas” (lubricant).

When Rosa testified before the court, she said it was Angie who thought up the code words “in order to make it sound less vulgar.” Priorities people.

Regional slang

Disgraced Constitutional Court Chief Justice Akil Mochtar liked to keep things local. When he took a bribe to sway the results of an election in Lebak district, Banten, he asked for some ekor, or tail, instead of billions. In the Palembang city election, it was pem pek, a tasty fish cake that originated in the city. In Gunung Mas, Central Kalimantan, it was “three tons of emas“—or gold—in a reference to the district’s name.

Islamic terms

These stem from a corrupted Quran procurement contract at the Ministry of Religious Affairs, so it makes sense to use common Islamic words, I guess. The case involved “santri” (or Islamic student) or messengers, “imam” (Islamic leader) as a ministry official, “murtad” (apostate) for something deviating from the deal, “kyai” (Islamic teacher) for lawmakers, and “pengajian” (Quran recitation gathering) for “tender process.”

The list could probably go on forever because the terms are always changing. KPK Commissioner Alexander Marwata said that the anti-graft agency was always working hard to crack another new set of code words.

“The codes used by corruptors always change,” he said. “Our operations to catch them red-handed only made these corruptors more careful in their communication.”