The fall of 1997 was, simply put, one of the most remarkable movie-going seasons of our time: Boogie Nights. Jackie Brown. The Sweet Hereafter. Wag The Dog. Eve’s Bayou. Good Will Hunting. The Ice Storm. Amistad. As Good as It Gets. Gattaca. And so many more, culminating with what became the highest-grossing movie of all time: the long-delayed, oft-trashed, yet eventually unstoppable Titanic . Each week yielded another remarkable motion picture—sometimes two or more, taking bold risks, telling powerful stories, introducing formidable new talents, and reaffirming the gifts of master filmmakers. This series looks back at those movies, examining not only the particular merits of each, but what they told us about where movies were that fall 20 years ago, and about where movies were going.

I must confess that, when I put together a list of great movies from the fall of 1997 to revisit 20 years later, I didn’t anticipate the most controversial and difficult selection would be Wag the Dog. Barry Levinson’s snappy political satire was a critical favorite late in the year and a sleeper hit early in the next one, thanks in no small part to its inadvertent analogues with the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal.

Videos by VICE

But it generated headlines of a different kind earlier this month, when a panel discussion at a 20th anniversary screening turned into a heated tête-à-tête between moderator John Oliver and co-star Dustin Hoffman, who has been the subject of multiple accusations of sexual misconduct. Part of the reason for raising the issue, Oliver explained, was that the film they were there to celebrate concerned sexual misconduct by a powerful man.

And does it ever. In its very first scene, Washington fixer Conrad Breen (Robert De Niro) is brought to a political bunker several floors below the White House and briefed on the situation: the President has been accused of sexual misconduct with an underage girl who was visiting the Oval Office with her group of “Firefly Girls.” Breen doesn’t care if the story is true: “What difference does it make if it’s true, if the story breaks, they’re gonna run with it.” The president is less than two weeks away from certain re-election, so Breen’s strategy is simple: “We just gotta distract ‘em… Change the story, change the lede.”

A scandal this big requires a big distraction, he reasons, so he comes up with one: a war. Not an actual, expensive war, mind you, but the appearance of one. And for that, he goes to Hollywood, where he appeals to super-producer Stanley Motss (Hoffman). “War is show business,” he tells him, and Motss gets right to work, putting his team together for a brainstorming session. They work up slogans and campaigns, record hoary ballads and country songs, and fake a piece of ubiquitous news footage (featuring Kirsten Dunst, who, in a single scene, does a marvelous little satire on biz-savvy child actors).

The Oscar-nominated script, adapted by Hilary Henkin from Larry Beinhart’s book American Hero and re-written heavily by David Mamet (his second big script of the fall), is full of tasty Mamet bon mots like “A good plan today is better than a perfect plan tomorrow,” and sharp exchanges like this one: “Our guy did bring peace.” “Yes, but there wasn’t a war.” “All the greater accomplishment.” De Niro and Hoffman trade those lines like jazz musicians, and Anne Heche gets the film’s signature Mamet Curse-Out, giving it to Hoffman from both barrels when one of his plans finally goes off the rails.

Wag the Dog works as satire because of a political world that keeps running the same plays on the media—who, in turn, keep falling for them. If anything, in the years since its release, the worlds of politics, entertainment, and news media have grown even more intertwined in which narratives are carefully controlled and expectations are minimal. Much of that commentary was missed in early 1998, as viewers and pundits honed in on the parallels to the Clinton affair (there were even similar photographs of its President and his beret-clad accuser). But now Wag the Dog takes on a more sinister undercurrent; it is, after all, the story of a machine of enablers working to cover up the sexual misdeeds of an important man, and we’ve been hearing variations of that story all fall. Put into that context, the laughs stick in the throat—and Hoffman’s catchphrase in the face of disaster, an assured “This is nothing,” sounds less like a running gag and more like a refrain of complicity—or, in his particular case, the shrugging dismissals of an accused predator.

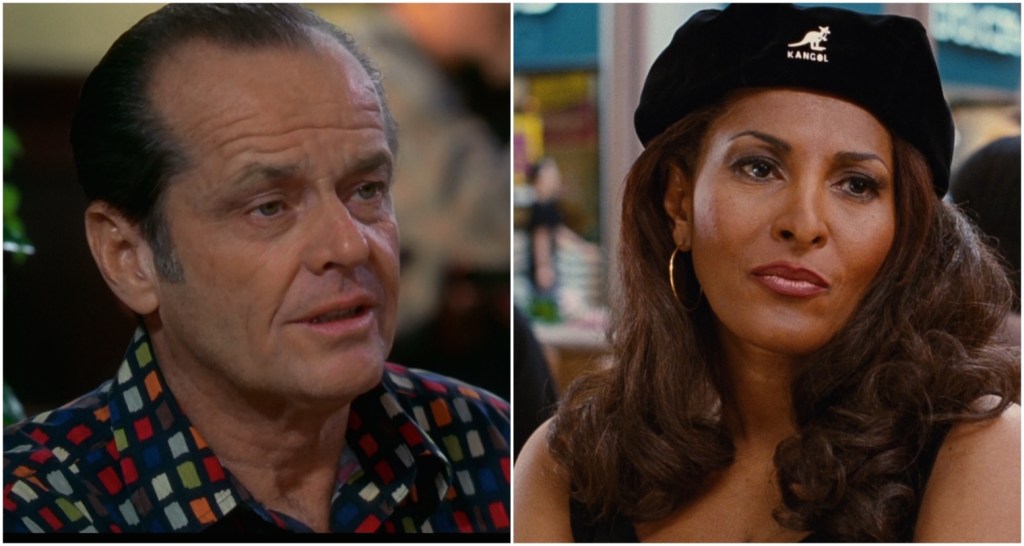

James L. Brooks’s As Good As It Gets similarly hasn’t aged quite well. It takes great pains to paint protagonist Melvin Udall (Jack Nicholson) as something of a 90s Archie Bunker—a “politically incorrect” but lovable curmudgeon who says “fudgepacker” and “fag” and “colored,” but in ornate, well-paced comic speeches, delivered under the devilish eyebrows of good ol’ Jack.

To be sure, Brooks does try to make Melvin a genuine S.O.B.—the picture does open with him dropping a cute dog down a garbage chute. He also suffers from obsessive compulsive disorder and difficulties with social interactions; one of his best acting moments comes early, when Brooks lets the actor take an eternity to realize he’s said the wrong thing to someone, and react.

That someone is Carol, the only waitress who will tolerate him at the only restaurant he’ll eat at. She’s played by Helen Hunt, who is very good in a near-impossible role. Brooks’s script requires her to be saintly in her patience with Melvin, while standing up to him when it’s necessary; she also plays the concerned mom to a sick kid as well as the magical muse for Melvin’s artist neighbor (Greg Kinnear), inspiring him back into productivity by letting him draw her nude. (It was a big year for nude drawing.)

As Good As It Gets is an odd film. On one hand, it’s Brooks’s film that most betrays his TV sitcom roots, thanks to its one-liners, the cutaway-reaction style of its shooting and cutting, and moments of broad stereotyping, particularly by Kinnear and Cuba Gooding Jr. But it’s also one of his more ambitious works, packing in subplots and subjects by the handful—indicative of a filmmaker who seems to genuinely struggle with the confines of the genre.

It’s a sticky movie, in which its maker forces himself into straight-up contortions in order to arrive at the “love conquers all” ending—quite a contrast from that of his Broadcast News a decade earlier. It’s an unfortunately conventional conclusion, and unconvincing too—just watching the insult/apology/reconciliation pattern of these two is exhausting, so it’s hard to imagine choosing to experience it. Yet the performers are top-notch, several individual scenes are gems, and if nothing else, “Sell crazy someplace else—we’re all stocked up here,” remains both a great line of dialogue and a helpful rejoinder for use in one’s daily life.

For many of us, that Christmas Day also brought the gift of the most exciting release of 1997: Jackie Brown, Quentin Tarantino’s long-awaited feature follow-up to his game-changing 1994 smash Pulp Fiction. And, in many ways, it’s right in the tradition of his breakthrough—a lengthy, sometimes leisurely crime picture, resurrecting a big star of the 70s (Pam Grier) matched up with force-of-nature Samuel L. Jackson, backed by a supporting cast of big stars, forgotten faces, and points between.

Yet he specifically, pointedly chose not to make a Pulp Fiction 2. At the time, there was some resistance and disappointment among fans, who took to that embryonic version of the movie internet to express frustrations about the film’s pace, style, and approach. And to be sure, while it runs about as long as Pulp Fiction, it’s a slower movie—because it’s moving at the pace of its protagonists, Jackie Brown (Grier) and her bail bondsman-cum-partner in crime Max Cherry (Robert Forster), the former approaching middle age and the latter just on the other side of it.

And Jackie Brown is slower because of the time Tarantino takes for human moments: charismatic villain Ordell (Jackson) in the front seat with a man he’s about to kill in the trunk, taking his time and popping in his Brothers Johnson tape; Ordell carefully thinking through how his plans have gone awry when he’s in the van with Louis (De Niro, again); Jackie’s moment alone after she hangs up with Ordell, contemplating the confrontation she can no longer outrun; and most of all, the closing shot of Jackie sadly singing to herself as she drives away from a good man (and holding on a face as a song plays—and holding, and holding, a moment Paul Thomas Anderson seems to echo at the end of Magnolia two years later).

Because Tarantino was hot off of Pulp Fiction, he had the power to cast Pam Grier, who hadn’t fronted a major movie since her 70s blaxpoitation heyday—as well as casting Forster and De Niro in lead and supporting roles, rather than the other way around. He also had the resources to buy the rights to and adapt Rum Punch, a novel by his storytelling idol Elmore Leonard, merging his nostalgic sensibility with Leonard’s real-time concerns.

There are flashy and funny scenes all over Jackie Brown, but when I think of it, I think of the casual morning coffee chat between Jackie and Max, sitting at her dining room table. They talk about not only aging, but growing more comfortable with yourself as you get older. It’s two great actors bringing their own personalities and experience to bear on a fictional scene—Jackie and Max talking, but also Pam and Robert, about trying to age gracefully and remain employable in the entertainment industry. And it just wouldn’t play with the same truth if it were between two big-time movie stars.

Jackie Brown didn’t turn Grier and Forster back into marquee players the way Travolta did after Pulp Fiction, which was probably to be expected as it didn’t have the same cultural or commercial impact. But it kept them working steadily for years thereafter, and fans who found Jackie Brown too stately or deliberate would be more than satisfied by his next film, the blood-spurting two-part Kill Bill epic. Those films are a lot of fun, and so are most of his works—but Jackie Brown may be the only Quentin Tarantino movie that gets noticeably better with each viewing. That’s not a knock on the other work, but a testament to this one; to repurpose the Dazed and Confused line, I keep getting older, but Jackie and Max stay the same age. Each time I go back to it, they’re sitting there sipping their coffee, waiting for me to catch up.

Jackie Brown wasn’t a giant hit that fall, but then again, not many of the movies we’ve looked at in this space were—aside from Titanic, its $600 million domestic gross more than doubling that of the year’s second-highest grosser, Men In Black. Good Will Hunting ended up with $138 million, a slow but steady performer that picked up steam as it accumulated year-end accolades and awards; ditto As Good As It Gets, which put up $148 million and ended up winning Oscars for both Nicholson and Hunt. Aside from those three, the only fall movie in the year-end top 20 was Disney’s Flubber remake.

And the numbers are where we find the lessons Hollywood learned from this extraordinary fall of 1997, because that’s what they pay attention to—not reviews, not awards, but money. The runaway success of Titanic that December marked a sea change in how movies were placed on that calendar. Its prestige trappings and length aside, Titanic was more considered, at that time, a summer movie than a fall/winter one (and it was originally scheduled to debut there). But it was such a juggernaut that it not only cleaned up with the holiday crowd but continued to steamroll the traditionally weak new releases in the early months of the following year, remaining in the #1 box office slot for a staggering 15 weeks before finally dropping to #2 the weekend of April 3, 1998.

The takeaway was that while Titanic had been a big risk—at a heretofore unheard of $200 million budget—it had also reaped a big reward. The studio releases of the fall of 1997 were, comparatively speaking, modestly budgeted; L.A. Confidential cost $35 million, Amistad cost $36 million, The Game, $50 million. They made back their money, and a little besides. Titanic, though costing several times more than films like those, also out-grossed that gap several times over. In the years ahead, studios would shift to a model of bigger bets, spreading their money over of fewer movies that cost more, as well as looking to alleviate those risks by investing in familiar properties with tentpole potential.

The four-tiered system that made the fall of 1997 such a fruitful period—low-budget indies like Eve’s Bayou and Happy Together, higher-budgeted and higher-profile films from the “mini-majors” like Boogie Nights and Good Will Hunting, mid-budget studio prestige pictures like Gattaca and As Good As It Gets, and big-money blockbusters like Titanic and Starship Troopers—would, in the years to come, collapse into two: the super-pricey and the super cheap, with the latter taking on most of the movies in the middle. When something like As Good As It Gets gets made today, it’s for a quarter of that cost, tops; something like Kundun or Amistad might not get made at all.

Have the movies suffered? Maybe not; I’d put the class of 2017 up against the class of 1997 without much hesitation. But those heady, pre- Titanic days do feel like the end of an era, in which big risks weren’t verboten, complexity was encouraged, and an environment was fostered in which vibrant, exhilarating, yet personal works like Jackie Brown, L.A. Confidential, and Boogie Nights were not only possible, but commonplace. It’s probably a naïve perception, and the alignment of masterpieces over those four months was more coincidental than engineered.

But then again, movies like these make you feel like anything’s possible.

Follow Jason Bailey on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: ConcernedApe -

Screenshot: Red Barrels -

Marlon Wayans / Instagram -

Collage by VICE