“It’s all about people doing something else other than what they have done, because what they have done is the possible,” said musician, philosopher, and pioneer of Afrofuturist ideologies Sun Ra in a 1971 interview about his artistic mission. “And the world the way it is today is results of the possible that they did. It’s a result of the absolute thing. So now, there’s always something else in a universe as big as this.” The main source of inspiration for Sun Ra’s fixation on heading to the cosmos was that life on Earth, as it was (and is) currently situated, was an unfit habitat for black people. In the 61 years since the release of his debut album, Sun Ra’s sophisticated rendition of trauma-inspired escapism has taken a number of shapes. Most recently, Marvel’s Black Panther gave a dazzling depiction of what life would be like in an African country that hid its wonders from the rest of civilization.

That thinking has also evolved in the world of music. Artists like Janelle Monae have made a career out of reimagining themselves as being part of something much more enjoyable and affirming than what the world tends to give black people. Afropunk, the music festival that launched in Brooklyn, started as a safe haven for black alternative types, but has morphed equally into an event where young people present themselves in ways that are much more fit for an advanced world. At the festival’s first installment in Johannesburg in late December, Belgian-born and South African–raised artist Petite Noir helped carry on this legacy when he took the stage at Constitution Hill.

Videos by VICE

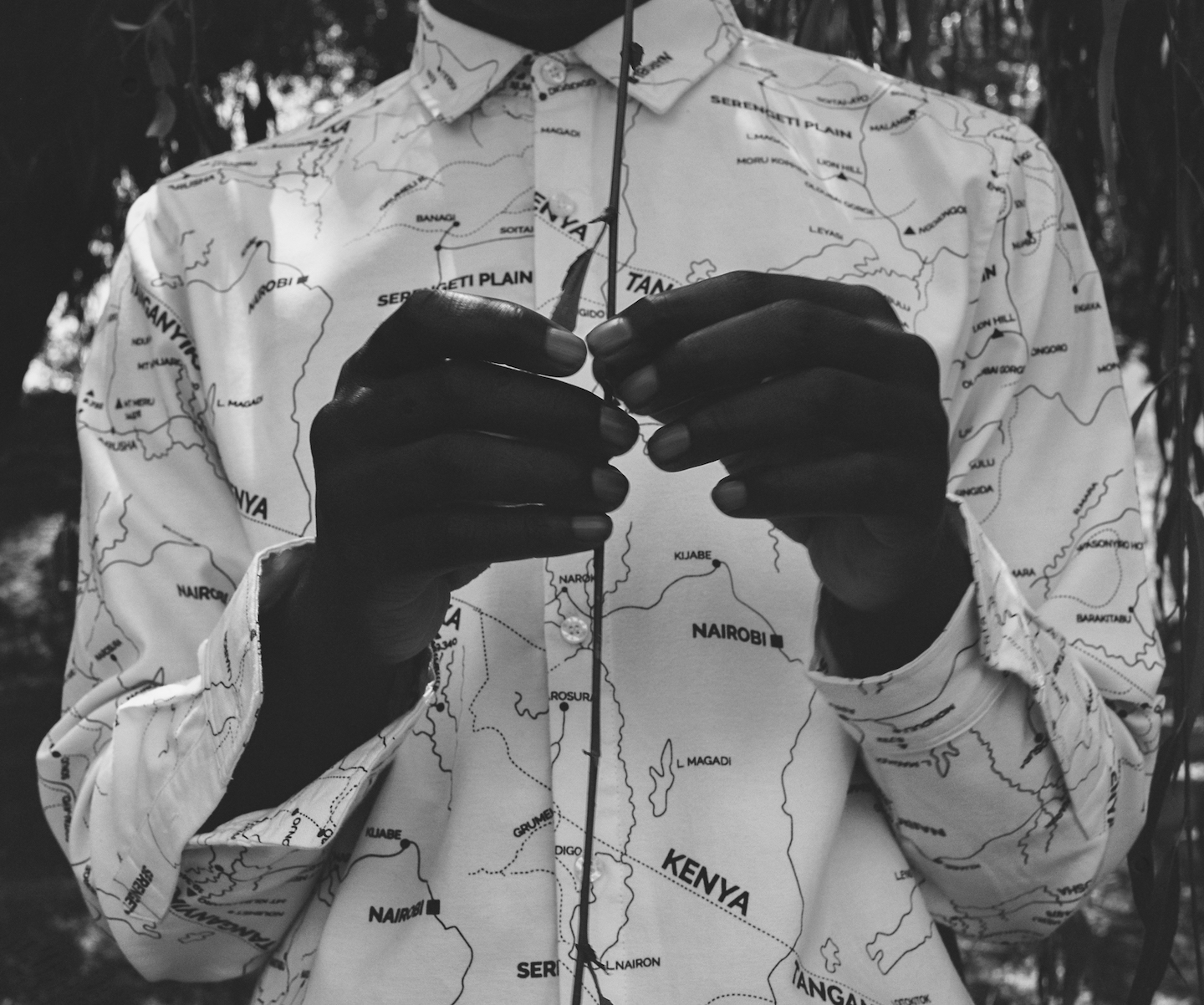

Noir’s music is a blend of punk, pop, and soul that takes as much inspiration from indie rock as it does from the guitar music being made in his native Congo. When joined with the visual aesthetics that he and his wife create under their Noirwave collective, his message of a futuristic African continent is made much clearer. In videos, Noir stand with cloned versions of himself and runs through fields of an unknown world with warriors that don’t seem to belong to any contemporary African nation. This is all part of the plan. To Noir, Africa as a whole is stuck in a strange crossroads of becoming the Western world’s idea of metropolitan while still trying to maintain ancient practices. Neither paradigm is useful in the borderless African continent that he imagines for himself.

Over lunch in Johannesburg’s Maboneng precinct, I talked with Noir about his idea of what a future Africa looks like, why he’s never fit into South African society, and how his music reflects all of his ideas.

Before I came to Joburg, I thought that people’s art would be more tied to being the first generation out of Apartheid, but it seems like most people don’t wanna make work that kind of way. But being originally from Congo, you said that you never quite fit into those politics. Did you feel like that as soon as you got here?

When I was a kid, I didn’t really feel anything like that, you know. Only when I got older did I start realizing the borders. That’s when separations came through. There are people out here like me who are from other countries. There are some people with a similar mindset. School wasn’t really bad. I didn’t fit in but I fit in. I had my group of friends.

Your path musically seems a lot different than most of your peers in South Africa.

Yeah. I had a group of friends that were just into other stuff. A lot of my friends were artists. Most of my friends were from home, rather than from school. Cape Town’s really small. Also having the Congolese influence on the music. Congolese music’s more guitar-based and it has more of a Cuban feel. Because during the Cold War, Che Guevara did a lot of stuff in Congo like helping out troops. A lot of Cuban soldiers went to Congo. So the music actually stayed. Congolese music sounds like salsa. So I started playing the guitar from that and from there, went into other guitar music.

Well, when I say different, I mean not only your sound, but even the way you’ve navigated the music industry. Do you feel like your connections to different places growing up made you feel like you could make it elsewhere?

I’ve had a plan in mind that I’m gonna make it no matter what. I’m a lone wolf. I do everything alone. I just listened to music when I was younger. I didn’t choose to start doing this. I was into all kinds of music. I went from like punk music, to hip-hop, to African music. And they all came from different sources. I was into anything weird and different.

I’ve noticed that the radio here is almost exclusively American music. It’s crazy. I was hoping I would get here and learn some shit.

It’s South Africa, man. The name itself, it’s an English name—that’s the sign already. I think through traveling, my brothers and sisters always put me on to different things.

Do you think places like Joburg have enough going on where you could sustain your career here?

Definitely. They’re some really big local guys here like eMTee and that whole side of things. It depends on what kind of music you make. And also, I don’t really believe in staying in one place and just making music here. I could never do that. I’ll go crazy. I think as an artist you have to travel. You have to try to experience other things besides your own.

It was interesting to hear you talk about Afrofuturism—because from my Black American experience, our connection to Africa is still not based on a contemporary Africa. Even the Pan-africanism, in ways, was still trying to capture something that we missed out on. I think most of our references are not tied to the now.

So the thing is, the world and also Africa, is moving towards this cosmopolitan sort of idea. But that whole thing is a Western idea. So you might feel like you’ve already seen this.

What came first? Your interest in sci-fi or your imagination of what you can create and how it lines up with sci-fi?

For me and my wife, Rharha, it was always about creating something completely new. And always not being from here. So I don’t have that mentality of a local person. I’ve been on the move my whole life. It’s not necessarily because my family is rich so we moved place to place. They had to move. Otherwise we would have been killed. So that mentality of being a refugee—even though I hate using that word—is like forced me to think this way. She’s the same.

You have to sort of create this world. As a South African person, it’s easy for them to make South African stuff. So they’re always gonna choose a South African person over me. So I have to make my own or go bigger. It’s a weird dynamic that I haven’t sat down and thought about.

Seems like you’re going deeper into creating your world and imagining what that world could be. Where is that inspiration drawn from now. Has it changed over time?

I think now I’m constantly looking at myself. I’m going back to Congolese things and mythology. But I don’t like to do that. I don’t wanna ever be like a local anywhere. Even if I go there, people will be like “what the fuck?” So there’s nowhere in the world where I can actually fit in. So I’m just on a journey. I don’t know where I picture my life. But as long as what I do is empowering to wherever I am.

Has your music empowered you as much as you’d like to empower other people?

I guess I’d like to think that I’m empowered. Or I’m more mentally free in my thinking. So in knowing that, I sort of make music to make people think that same way. I think that’s sort of a thing that needs to happen more. I think that’s why I’m here. Especially with my family—my dad was in politics and I think some of those characteristics carried into me. My medium is just different. I don’t think that makes me any more or any less than anyone else, I just think that’s my purpose on that planet.

More

From VICE

-

(Photo by Carlos Alvarez/GC Images) -

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

Getty Images/Peak Design -

Getty Images