In late autumn of 1964, Wong Jack Man piled into a brown Pontiac Tempest with five other people as the sun set on San Francisco Bay. The group departed Chinatown and traveled east over the Bay Bridge to Bruce Lee’s new kung fu school on Broadway Avenue in Oakland. After weeks of back-and-forth messages and rising tensions, high noon had finally arrived.

The showdown that occurred that night in front of just seven people behind locked doors was a legendary matchup by just about any standard. It posited two highly dynamic 23-year-old martial artists who shared a compelling—almost yin/yang-like—symmetry between them: the quiet ascetic and the boisterous showman, traditional against modern, San Francisco vs. Oakland, Northern Shaolin against Southern. The fight that ensued would affect the remainder of both of their lives. And even still, this symmetry would persist: one would silently endure the fight’s long shadow for decades, while the other would boldly become a global icon before passing all too soon.

Videos by VICE

Far more than just some youthful clash of egos, the incident has a much wider relevance. Not only did it shape the fighting approach of the man who would become the world’s most famous martial artist, but the match itself was a key moment in a battle of paradigms. If Bruce Lee is indeed a philosophical godfather of modern mixed martial arts competitions, then his fight with Wong Jack Man was a qualifying moment, a crucible that tested the validity of martial techniques much in the way that early UFC fights would in the late 90s, tearing back the curtain to bluntly expose what was effective and what was mere hype.

Yet this context has mostly gotten lost in the shuffle over the past half-century, as the showdown seems to permanently teeter between absurd urban mythology and obsessive hero worship of Bruce Lee. With Hollywood gearing up to release its latest sensationalized rendering of the fight, a new wave of misinformation is already starting to take hold. George Nolfi’s hyperbolic new film Birth of the Dragon will frame Wong Jack Man as a Shaolin Monk on pilgrimage who eventually teams up with Lee to battle the mafia. This movie will file in alongside the often-maligned 1993 biopic Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story, which framed the fight as a dungeon battle in front of some kind of elder ninja counsel, concluding with Wong cheap-shot kicking Bruce in the spine.

By simple contrast, the factual history is infinitely more compelling than the mythology.

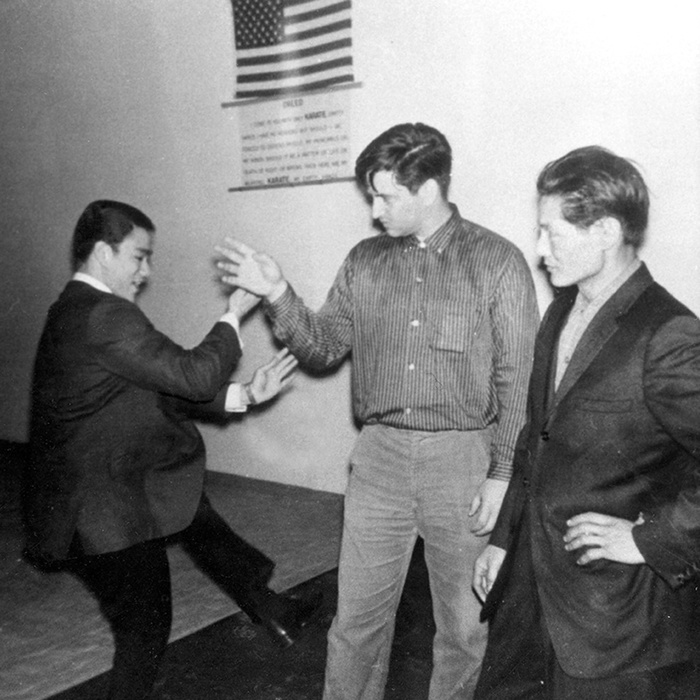

A young Bruce Lee with key Oakland-era colleagues Ed Parker (center) and James Lee in Ralph Castro’s kenpo school in November of 1963. Bruce had found a very likeminded group of martial artists within James Lee’s orbit in Oakland, and would soon relocate from Seattle to continue collaborating with them. (Photo courtesy of Greglon Lee)

Oakland

By the early 1960s, the San Francisco Bay Area was home to a robust martial arts culture that was populated by a diverse array of talented practitioners, who hailed from southern China, Hong Kong and Hawaii. Bruce dropped out of college, and abruptly left a good situation that he had built for himself in Seattle, to participate in this pioneering scene in the Bay Area.

Most notably, he took up residence in the city of Oakland to collaborate with James Lee (no relation), a blue collar local who was twice Bruce’s age, who had a lingering reputation for his youthful days as a no-nonsense street fighter and body builder. Yet James was also a brilliant innovator for the martial arts in America, and was already enacting the sort of martial arts future that Bruce was just beginning to envision. James was publishing his own books, designing his own workout equipment, and running a very modern training environment out of his garage. He quickly introduced Bruce into his orbit of talented and progressively-minded colleagues, which included innovative jujitsu master Wally Jay and early American kenpo karate pioneer Ed Parker. In 1963, James would produce Bruce’s first book—Chinese Gung Fu: The Philosophical Art of Self-Defense—through his self-run publishing company.

Altogether, Bruce very much found what he had wanted in Oakland: a unique martial arts think-tank laboratory where he could practice and discuss martial arts 24/7 among experienced and likeminded collaborators. These Oakland days encapsulated key milestones in Bruce’s life, including the creation of the only book he ever published in his lifetime, getting noticed by Hollywood, his fight with Wong Jack Man, and his initial development of Jeet Kune Do. However, this era typically gets minimal attention in most biographical works, despite its formative significance. In keeping with that trend, Birth of the Dragon will not only omit the likes of James Lee from its storyline, but also completely drop Oakland from this history, and instead set the entire era within San Francisco, where things were very different for Bruce.

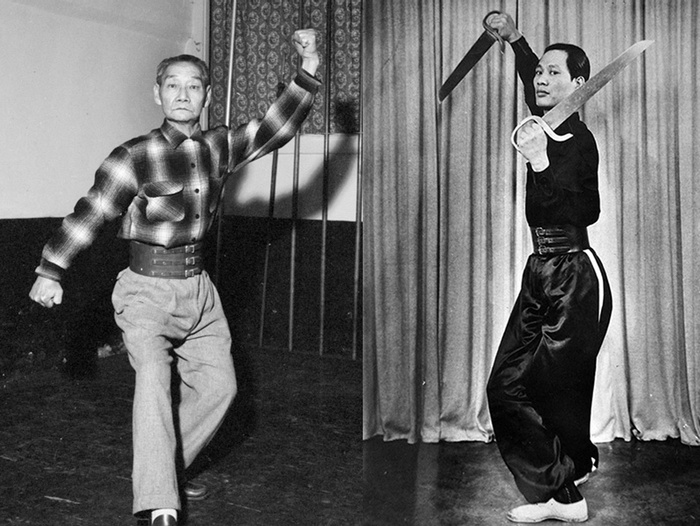

Lau Bun (left) and TY Wong governed the martial arts culture within San Francisco’s Chinatown for three decades. Most descriptions of the Bruce Lee/Wong Jack Man fight have little context for Chinatown’s martial arts culture and how it factored into the affair. (Photo Courtesy of UC Berkeley)

Chinatown

Across the water from Oakland within the city of his birth, Bruce Lee was perpetually at odds with the martial arts culture of Chinatown. In fact, there is a laundry list of little-known incidents and tensions that occurred between Bruce and Chinatown martial artists dating back to when he first returned to America in the spring of 1959. As Bruce quickly learned, San Francisco’s martial arts culture operated in very different fashion from the one he experienced in Hong Kong as a teenager.

For about three decades, Chinatown’s kung fu culture was presided over by two longtime local tong enforcers—Lau Bun and TY Wong—whose trailblazing careers have mostly fallen into obscurity. In the 1930s, Lau Bun opened Hung Sing, which is likely the first public school of the Chinese martial arts in America. He maintained a rigid discipline over his students and other martial artists within the neighborhood. For years, Lau Bun did not allow Chinatown to devolve into the sort of daily youth violence that Bruce Lee grew up around on the streets (and rooftops) of Hong Kong during the 1950s, where students from rival martial arts schools regularly challenged each other to fights.

Lau Bun (center) with senior students in Hung Sing, his basement training studio off of Portsmouth Square in San Francisco’s Chinatown. In 1959, 18-year-old Bruce Lee would have a little known run-in with this crew. (Photo courtesy of UC Berkeley)

TY Wong arrived to San Francisco in the early 1940s. As a junior tong member to Lau Bun, it often fell to TY to clean up rowdy and drunken behavior around the neighborhood’s Forbidden City nightclubs. The name of his school—Kin Mon—translated to mean “the Sturdy Citizen’s Club.” And like Lau Bun, TY expected a specific code of conduct.

Word of Hong Kong’s challenge culture and the tenacious reputation of its Wing Chun practitioners had preceded Bruce Lee to San Francisco. Bruce had spent his teen years learning Wing Chun kung fu within Ip Man’s school in Hong Kong, where he enthusiastically embraced the simple and streamlined nature of the style. Economical, swift and direct, Wing Chun emphasizes in-fighting along the opponent’s center line, employing short kicks and rapid punches in close proximity. The had a reputation for being results-oriented, and on the streets postwar Hong Kong, that was a crucial distinction.

Not long after arriving to San Francisco in 1959, Bruce Lee had a heated incident with Lau Bun and his senior students in Chinatown. “When Bruce came to Hung Sing, he didn’t know anything about San Francisco,” recounts Sam Louie, one of Lau Bun’s senior students at the time. “There were seven or eight of us in class. He came down to show off some hands, and tried to say to us that Wing Chun was the best. So our sifu threw him out.”

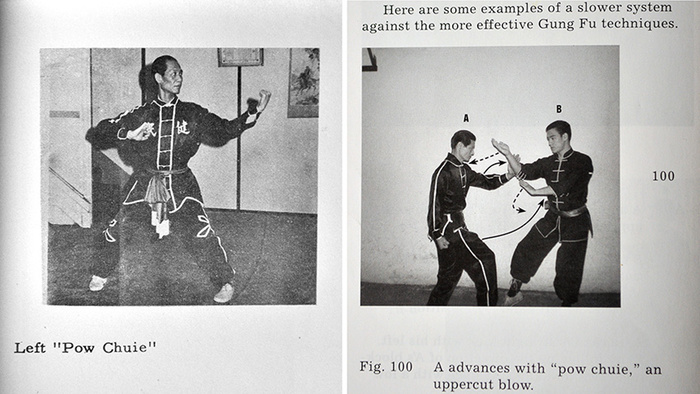

A comparison of technique stills from TY Wong’s 1961 book, Chinese Kung Fu Karate, alongside imagery from Bruce Lee’s 1963 book, Chinese Gung Fu. TY, Bruce and James Lee would all package insults into their books from this era, aimed between Oakland and San Francisco.

Instantly then, Bruce had gotten off to a bad start within Chinatown. These tensions would only build over time as he increasingly became a vocal critic of traditional approaches to the martial arts, which—in his minimalist Wing Chun mindset—he saw as heavy on flair but short on effectiveness. One of the most pointed examples of Bruce’s criticism is hidden in plain sight within Chinese Gung Fu…, where in a photo-by-photo case study, Bruce is seen dismantling specific techniques that are put forth in one of TY Wong’s earlier books. This is featured in a section titled “Difference in Gung Fu Styles,” in which Bruce distinguishes between what he sees as “superior systems” (namely, his own) versus “slower…half-cultivated systems” (that of TY Wong and other “more traditional” masters like Lau Bun). Bruce’s book was readily on sale within Chinatown, and the insults were not lost on locals. So when TY Wong subsequently characterized Bruce Lee as “a dissident with bad manners,” it was a view shared by most martial artists within Chinatown.

At about the same time of Bruce’s book being published, Wong Jack Man showed up to Chinatown, and quickly made a name for himself as a dedicated and highly skilled practitioner. He was the first to bring a northern to the neighborhood, and he proved “elegantly athletic” in demonstrating it. In many ways, his appeared to be an inverse of Wing Chun: expansive, acrobatic, and oriented around long-range attacks. Chinatown was quickly impressed with Wong Jack Man, and embraced him in every manner that they had shunned Bruce.

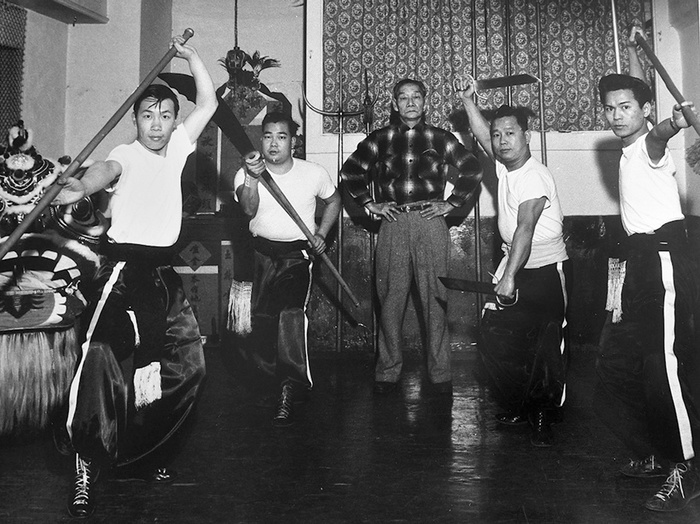

TY Wong (standing, 2nd from right) with his teenage students in his Kin Mon Physical Culture studio on Waverly Place in Chinatown. Notice his one white student (Noel O’Brien) on the top right, who followed Al Novak in a steady stream of non-Chinese students that TY taught throughout the 1960s. (Photo courtesy of Gilman Wong)

“Chinese-Only…?”

The long-held rationale for Bruce Lee’s fight with Wong Jack Man has asserted that top brass in Chinatown took exception to Bruce teaching non-Chinese students kung fu, and sent Wong Jack Man over to Oakland as an enforcer to settle the matter with fists. This theory, which was rendered in heavy-handed fashion in Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story, has always been completely void of details as far as who exactly took exception. If anyone in Chinatown was to make this call, it would likely have come down from Lau Bun or TY Wong. Yet, there is not only scant evidence to support this, but developments at the time prove highly contrary to this perspective.

When asked about the idea that Chinatown sought to reprimand Bruce for teaching non-Chinese, Al Novak—a hulking WWII veteran and close friend of James Lee—shrugged it off, “I think that’s mostly made up.” Novak would know, because by 1960 he was a white student regularly training with TY Wong at Kin Mon in Chinatown without incident. A few years later, TY took on Noel O’Brien, a local Irish teenager. In Hung Sing, Lau Bun was training a Hawaiian named Clifford Kamaga, and also showing no open opposition to his senior student Bing Chan, who was accepting all types of students at his own newly-opened school just a couple blocks away in Chinatown.

Lau Bun (2nd from top right, with glasses) standing with Hop Sing Tong members and a Lion Dance squad in Marysville, California, during Chinese New Year celebrations in 1961. Lau Bun’s Los Angeles colleague and noted kung fu master Ark Wong (2nd from top right) would eventually give a formal interview to Black Belt Magazine in 1965 expressing that he was open to teaching all types of students, regardless of race. (Photo courtesy of UC Berkeley)

Of course, the situation was not without nuance. Bruce Lee’s early classes, particularly in Seattle, were indeed groundbreaking for how diverse they were, in terms of both race and gender. And the Chinese-only martial arts code was a very real policy that existed for decades, and one that had surfaced against Bruce at various early points in his life. Yet the code was in its final throes by the 1960s. In fact, in early 1965 (very shortly after Bruce’s showdown with Wong Jack Man) Ark Wong, a well-respected kung fu master in Los Angeles, gave a high profile cover story interview to Black Belt Magazine in which he said in explicit terms that he was open to taking on any type of student willing to learn from him.

So for as tangible as the exclusion code had been, martial artists from the Bay Area—including many of Bruce’s colleagues—widely express skepticism at the idea of it being the core reason for that particular fight. “It was never about that,” says Leo Fong, a versatile veteran martial artist who knew the landscape well. “It really had to do with Bruce’s personality.”

Bruce Lee’s demonstration at Ed Parker’s inaugural Long Beach Tournament in August of 1964 is typically cited as a key moment in his career (in which he first get noticed by Hollywood), but is typically sanitized to omit the critical lecture he delivered to an international crowd of martial artists. (Photo courtesy of Barney Scollan)

The Dissident

By the start of 1964, Bruce began to double-down on his earlier criticism of “ineffective” styles and techniques, and began given lecture-heavy demonstrations featuring stinging rebukes towards “dry-land swimmers” practicing the “classical mess.” By contrast, he referred to his own approach as “scientific street fighting,” and made a habit of demonstrating other styles and then methodically explaining why they wouldn’t work in a street fight. One of the styles he liked to perform and then dismiss was Northern Shaolin, and he began to air these viewpoints to some very large and qualified audiences.

At Ed Parker’s inaugural Long Beach Tournament in August, Bruce delivered a scathing lecture that disparaged many existing practices, including such common techniques as the horse stance. “He just got up there and started trashing people,” explains Barney Scollan, an 18-year-old competitor that day. Although Bruce’s showing at Long Beach is often painted in glossy terms, many of those in attendance corroborate the polarizing nature of his demonstration, in which half the crowd perceived him as brash and condescending. As longtime karate teacher Clarence Lee remembers it: “”Guys were practically lining up to fight Bruce Lee after his performance at Long Beach.”

In late summer of ’64, Bruce accompanied Hong Kong starlet Diana Chang Chung-wen (“the Mandarin Marilyn Monroe”) on a promotional tour of the U.S. west coast in support of her latest film. This brought them to the Sun Sing Theater, in the heart of San Francisco’s Chinatown where Bruce’s demonstration and critical lecture would infuriate the neighborhood’s martial arts practitioners. (Photo courtesy of UC Berkeley)

A few weeks later before a capacity crowd at the Sun Sing Theater in the heart of San Francisco’s Chinatown, Bruce gave a similar demonstration, and even went as far as to criticize the likes of Lau Bun and TY Wong by declaring “these old tigers have no teeth.” It was a considerable insult coming from a young martial artist towards two highly-respected members of the community.

At this point, a confrontation wasn’t surprising…it was logically inevitable, especially when considering that Bruce had been challenged for similar reasons in Seattle a few years earlier on far less provocation. That fight was also predicated on the content of Bruce’s demonstrations at the time, when local karate practitioner Yoichi Nakachi took issue with Bruce’s martial arts worldview and loudly issued a challenge. Yoichi pursued him for weeks. When the two finally fought, Bruce obliterated Yoichi with a rapid series of perfectly places punches and a knockout kick in an 11-second fight that left him unconscious with a fractured skull. Oddly enough, the entire affair tends to get shrugged off as meaningless; when really, it should be seen as a case study.

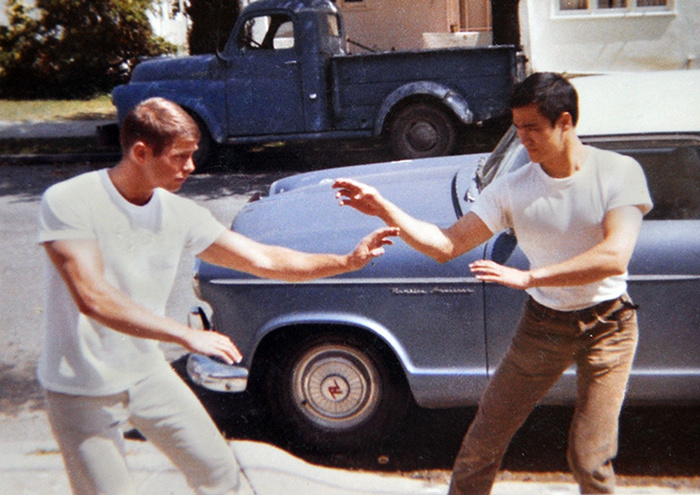

Bruce Lee with student Barney Scollan in east Oakland, where Bruce eventually relocated his school into James Lee’s garage. An earlier formal location on Broadway Avenue—where the Wong Jack Man fight took place—proved to be short-lived. (Photo courtesy of Barney Scollan)

“Made to Fight”

One of the most enduring questions that still remains difficult to answer, is—”Why Wong Jack Man?” Of all the practitioners in Chinatown to step forward to issue a challenge, why was it a recent transplant that had never even met Bruce Lee before?

There are two main theories on this. The first is that because Wong Jack Man was poised to open his own martial arts school in Chinatown, he stepped forward in an opportunistic moment to generate some publicity. Local tai chi practitioner David Chin asserts that Wong said as much when he signed a challenge note to be delivered to Bruce. Yet a more popular theory professed by many local sources from that era is that Wong Jack Man was duped into fighting Bruce, essentially the new kid on the scene goaded into a schoolyard brawl without grasping the stakes.

But who were those five people that drove over to Oakland with Wong Jack Man? In the front seat with Wong were David Chin and Chan “Bald Head” Keung, two martial artists that frequented the Ghee Yau Seah (The Soft Arts Academy), a sort of tai chi social club that had been established within Chinatown in the early 1930s. In the back seat, were a trio of hanger-on troublemaker types, with no strong connections to the neighborhood’s martial arts scene: Ronald “Ya Ya” Wu (whose nickname reflected his constantly yammering mouth), Martin Wong, and Raymond Fong. As Wong Jack Man would later put it, this group was “only there to see the hubbub.”

No one in the car was a student of TY Wong’s Kin Mon or Lau Bun’s Hung Sing, but tied instead to the Ghee Yau Seah. In fact, Lau Bun’s senior student Sam Louie remembers his school mates abiding by Lau Bun’s code of conduct and admonishing this crew as they riled themselves up that day prior to the fight: “We said, ‘It has nothing to do with Hung Sing.’ And we explained to them, ‘You go into someone’s studio…it’s no good. Whether you win or lose…it’s no good.’”

In Oakland, Bruce would only have two witnesses: his recent bride Linda Lee (who was 8 months pregnant at the time) and his close colleague James Lee (who had a loaded handgun nearby in case things spiraled out of control). This made for a total of nine people in the room, only three of whom are alive today. With a couple of very rare exceptions, Wong Jack Man has stayed perennially quiet on the matter. Linda Lee and David Chin, who were on opposing sides of the conflict, give a generally similar account: the fight was fast and furious, spilling wildly around the room. The exchange was crude, and far from cinematic. After landing an opening blow on Wong’s temple, Bruce struggled to decisively put away his evasive opponent like he had in Seattle a few years earlier, and quickly found himself heavily winded by the encounter.

Eventually Bruce’s relentless advance caused Wong to stumble over a small step, into an untenable position on the floor where Bruce hollered “Do you yield?” in Cantonese over and over while pummeling him repeatedly. Having lost his footing, Wong had no choice but to concede. “From there, he said he gives up and we stopped the fight,” recalls David Chin. “The whole thing lasted…not more than seven minutes.”

As with any good schoolyard fight, the exaggeration soon took on epic proportions. Storylines of Bruce slamming Wong’s head through a wall, or of Wong having Bruce in a headlock and ready to knock him out when the cops arrived, are just a couple among many. Perhaps the most absurd of the hyperbole, which is now a regular storyline in the press surrounding the upcoming release of Birth of the Dragon, is that the fight lasted for 20 minutes, a notion which is not only wholly inconsistent to the accounts of all proven eyewitnesses, but contrary to all basic sense for the nature of a street fight.

A rare image of Bruce Lee demonstrating techniques the night before the first Long Beach Tournament, in the summer of 1964. (Photo courtesy of Barney Scollan)

In the fight’s aftermath a war of words took place in local Chinese newspapers, in which both Bruce and Wong denied starting or losing the fight. In time, the urban mythology surrounding the incident would cite that Wong issued a call for a rematch in his article, though the exact wording suggests otherwise: “[Wong] says that in the future he will not argue his case again in the newspaper, and if he is made to fight again, he will instead hold a public exhibition so that everyone can see with their own eyes.” Although not an exact quote from Wong, the wording is curious—made to fight—and hints at the idea that Wong was indeed manipulated into the affair.

What is generally agreed upon is that Bruce Lee’s messy victory—light years from his precise 11-second win over Yoichi in Seattle—was a catalyst for him to finally overhaul his approach. For a martial artist who all year long had been so loudly professing the effectiveness of his technique against the inferiority of others, Bruce found the Wong Jack Man fight to be a sober reality check, in which both his technique and his conditioning came up very short of his expectations.

The timing was right for Bruce to begin tangibly forming his new system, Jeet Kune Do. He had already been synthesizing many of the influences that he had been exposed to in recent years—from James Lee’s street-fighter sensibility to Wally’s Jay’s propensity for innovation—to form an integrated system personalized to the individual. In creating Jeet Kune Do, Bruce incorporated elements of Wing Chun, fencing, and American boxing into a minimalist-based approach with a philosophical orientation.

Yet among the more egregious historical liberties that the new film appears to be taking, Wong Jack Man’s character will literally explain core Jeet Kune Do principles to him, as if it wasn’t the fight itself that impacted Bruce, but Wong’s personal martial arts wisdom.

+ + +

Bruce Lee (back row center) with one of his early Oakland-era classes operating out of James Lee’s (bottom row, third from left) garage, circa ’65. Bruce’s time in the Bay Area was was essential to his evolution as a martial artist, yet remains a largely obscure period of his iconic life. (Photo courtesy of Greglon Lee)

Today, when Bruce Lee is cited as “the godfather of MMA” it shouldn’t be merely for his sense of mixing styles (after all, others had done this in notable ways prior to him ever learning martial arts), but rather, for his emphasis on effective technique, and the constant evolution that is required to maintain it. This is the takeaway that gets lost amid the petty debates over the particulars surrounding the Wong Jack Man fight.

However, one of the most interesting postscripts (and there are many) to Bruce’s fight with Wong Jack Man falls to David Chin, the young martial artist who drove the Chinatown crew over to Oakland in late ’64. Despite standing that night with those opposed to Bruce Lee, David Chin is crystal clear on what he regards as the big picture: “The things Bruce was saying back then were true. I disagreed with him at the time, but he was right.”

Charles Russo is a journalist in San Francisco. This article contains information that is excerpted from his book – Striking Distance: Bruce Lee and the Dawn of Martial Arts in America.