Photographer Daniel Seiffert spent the first decade of his life in East Berlin, within walking distance from the Berlin Wall. Some of his most formative memories are from the autumn of 1989, when the concrete and barbed wire were torn down after 30 years of separation.

Two decades later, Seiffert would make his way to the eastern German town of Lübbenau, a two-hour drive from Berlin, with a friend who was studying urban sociology. Visions from his youth, long forgotten, reemerged; he recognized the socialist monuments, the flagpoles used in old May Day celebrations.

Videos by VICE

That first visit coincided with the demolition of the BKW Kraftwerk Jugend, a power plant responsible for tens of thousands of jobs. Lübbenau, the photographer explains, is what’s known as a “shrinking region.” Once a site of booming industry, it’s now rife with unemployment and abandoned buildings.

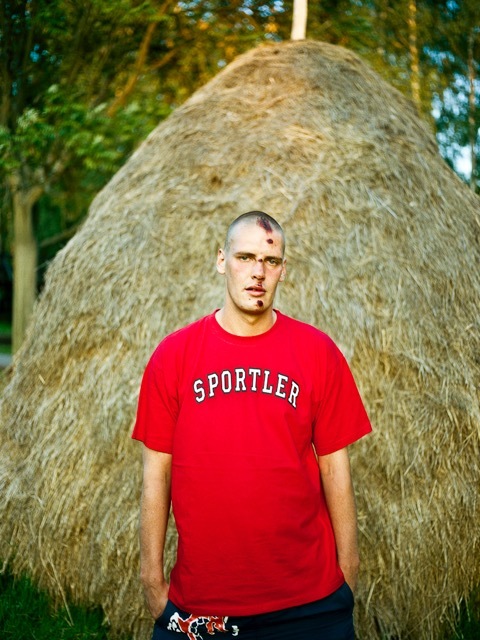

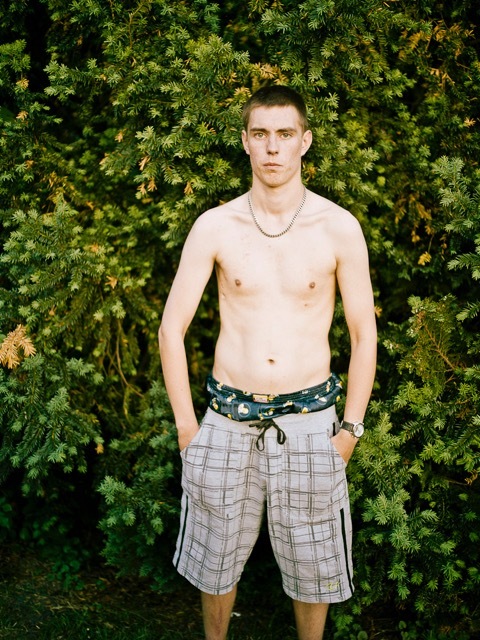

Over the course of a year and a half, Seiffert would make regular visits to Lübbenau to meet up with the local teenagers, who, for the most part, didn’t realize what the monuments and flagpoles had meant for the previous generation.

In the young people of Lübbenau, all born after 1989, the photographer witnessed an acute sense of restlessness. The town was becoming more consumerist and globalized, but most teenagers longed to leave behind the quiet life in search of real opportunity. Against the backdrop of a declining place, kids ached for adventure.

The kids Seiffert shadowed became friends; he accompanied them as they made their way through the neglected structures and graffitied landscapes, as they sipped beer and threw rocks through the windows of houses no one would ever miss.

He went with them to the mall and to the skatepark, the universal teenage kingdoms of the world, and he was permitted into their most sacred inner worlds, where few adults were ever allowed.

Though their lives were colored by the history of the GDR—many of their parents had worked in the coal mining before the reunification of Germany—they lived their own lives and diverged from everything that came before.

On some occasions, the adult presence did cause mistrust in those who didn’t know the photographer; one time, Seiffert feared a young man would punch him in the face, but the kids who knew the artist stuck up for him, and by the end of the day, that same boy was confiding in the photographer about a recent drunken blunder.

The power plant’s promise of prosperity had been broken, but in the wreckage, Seiffert discovered the crackling embers of first kisses, first fights, first heartbreaks, and first loves. The “furious energy” of adolescence, he suggests, filled the chasm left behind by the plant.

Seiffert dedicates the book Powerplant Youth to his daughter, born during the course of the project. At some point, he felt he needed to move on. He swapped teenage shenanigans for playing Legos and building forts.

In 2011, he put together the book, and when he exhibits the work, he plays an amateur YouTube video of the power plant demolition on a loop. The building erupts in smoke, falls to the ground, and nameless people laugh and cheer in the background.

Today, Seiffert is only in touch with a few of the youngsters he met. The successful ones have mostly left and found work in Berlin. The photographer has kept tabs as best he can; a few have pursued more education, and one is now a dental assistant.

Still, some remain in the limbo that is Lübbenau, and the world continues to turn. The photographer admits, “Those without hope and energy tend to stay.”

–Ellyn Kail

More

From VICE

-

Photo by Getty Images -

Hisayo Yamazaki stabds next to the puppets outside her house in the village of Ichinono. (Photo by Philip FONG / AFP) -

Lauren Levis, who died after taking iboga at the Soul Centro retreat in 2024. (Photo courtesy of the Levis family) -

Collage by VICE