This article originally appeared on VICE Sports UK.

In the aftermath of Manchester United’s win against Crystal Palace last week, there was an extremely predictable exchange on Match of the Day. With Zlatan Ibrahimovic having scored a late goal to win the game, Phil Neville – poor, sweet Phil Neville, forever doomed to be the less heeded of the Neville brothers – saw fit to brand him ‘world class’. The moment this most cliched of terms fell from Neville’s guileless lips, the mood changed in the studio, with Dan Walker taking on the reverential air of a high priest, fulfilling his duties as the custodian and defender of that holiest cornerstone of punditry: the ‘world class’ debate. Alan Shearer duly got the discussion going, pouring scorn on Neville’s assessment on grounds of Ibrahimovic’s age, stating that while the emblematic striker was, at one time, world class, the tag should no longer be applied to him owing to his diminishing abilities. In his own hastily mustered defence, this prompted Neville to come out with the immortal line: “Was, is – it’s the same thing,” hence showing his fundamental misunderstanding of the verb ‘to be’ and, indeed, the concept of time.

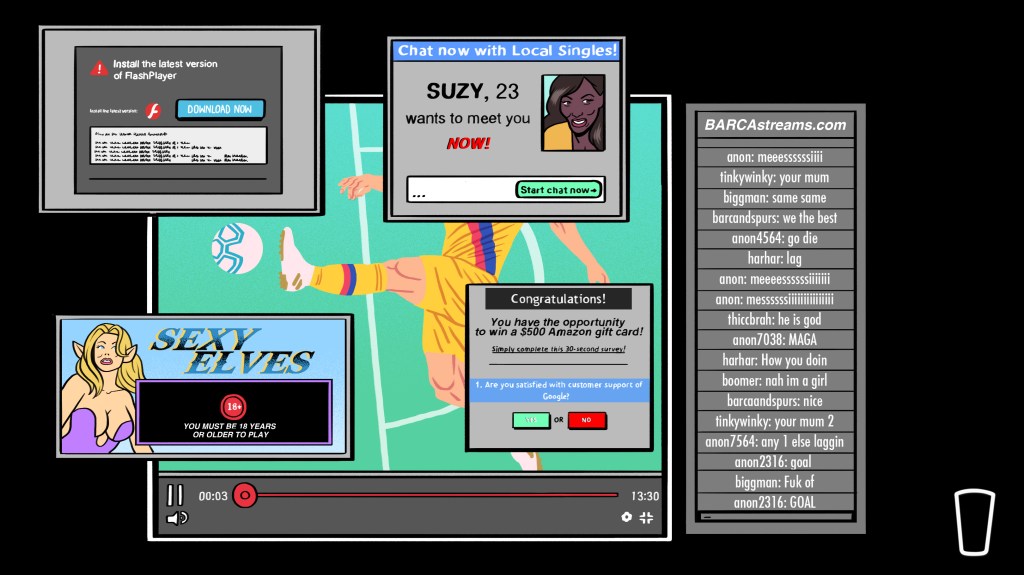

Videos by VICE

While Phil Neville’s argument was not, perhaps, the most elegant contribution to the eternal wrangle over whether or not any given football is truly world class, it did at least help to exemplify the utter pointlessness of said wrangle. The main problem with the ‘world class’ debate is that, on a fundamental level, the criteria by which ‘world class’ status must be judged is both subjective and completely arbitrary. Phil Neville might have radically miscomprehended the past tense but, then again, it was Alan Shearer who imposed the limits of time and age upon the discussion, as if the fact that Ibrahimovic is 35 years old automatically precludes him from the ‘world class’ bracket. Has there never been a player who has remained world class into his mid thirties? In answer, we give you Xavi, who won a domestic and European treble in his last season at Barcelona, making 44 appearances in all competitions despite seeing in his 35th birthday in the meantime. For other footballers who were still absolutely magnificent at the age of 35, see: Paolo Maldini, Javier Zanetti, Andrea Pirlo and Ryan Giggs.

With age an unreliable measure of ‘world class’ status, then, we must find another arbitrary gauge for an attribute that is intrinsically difficult to quantify. Over the many years that the ‘world class’ debate has been raging, criteria have ranged from a player’s club contributions to his international performances, or an ideal combination of both; their performances at major tournaments or their number of career trophies, regardless of performance; their statistical worth in terms of goals, assists, clean sheets and the like, or their imperceptible ability to fly in the face of statistics and still be great; their capabilities at set pieces, their close control, their passing range, their chance creation, their discipline; the worth of their endorsements, the value of their image rights, their estimated transfer costs; the number of FIFA covers they have been on, and how often they appear in global advertising campaigns selling cologne, or dietary supplements, or nutritional suppositories, or designer pants.

The fact of the matter is that, when it comes to ‘world class’ status, our collective frame of reference is ridiculously broad. There is no standardised measurement of what it is to be world class and, in lieu of some sort of doctrinal convention at which all the Match of the Day pundits get together and decide exactly what the fuck they are talking about, we are doomed to meander about in the fog of definitional uncertainty forevermore. Moreover, in the world of football, ours is a single frame of reference with an Anglocentric personality. To be truly world class, surely a player must have an appeal not just nationally, but globally. Unfortunately, what we consider to be world class in England might be viewed differently in Germany, or Italy, or Spain. The culture of the Premier League is distinct to that of the Bundesliga, for instance. The world is divided by variant understanding of what football is all about, and so the vast majority of attempts to define ‘world class’ status are doomed to fail.

There are a few players, a select few players, who somehow manage to transcend cultural variance. These men are too few to form an actual football team and, as such, even the idea of a ‘World Class XI’ is redundant to the point of oblivion. Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo are the only definites when it comes to global appreciation, with even the likes of Luis Suarez, Gareth Bale and Neymar far from universally loved. Then there is a burgeoning bracket of possibilities, including Sergio Aguero, Mesut Ozil, Robert Lewandowski, Gonzalo Higuain and, clearly, Zlatan Ibrahimovic. Whether or not these players are ‘world class’ depends on an impossibly disparate set of perspectives. Basically, everyone can agree that Messi and Ronaldo are the greatest, and beyond that bestowing ‘world class’ status upon someone is bound to be contentious to the point of being futile.

Of course, the conclusion that Messi and Ronaldo are a cut above everyone else is hardly revelatory. The best analysis we can draw from the ‘world class’ debate is that those two alone are objectively fantastic, which is hardly an informative way to look at world football, or even a useful inference to make. As such, the debate is not only hopelessly arbitrary and dependent on a grating cliche, it is redundant to its very core. May it be expelled from the Match of the Day studio forthwith, and so cease to needlessly consume any more of Phil Neville’s precious time.