WASHINGTON — It’s June 2020. Former Vice President Joe Biden ground out a win in Iowa, but Sen. Elizabeth Warren crushed him in New Hampshire. Biden narrowly beat Sen. Kamala Harris in Nevada, but she bounced back to win South Carolina a week later.

Crucial Super Tuesday ended in a split decision. Harris won a plurality in California while splitting the Deep South with Biden; Warren racked up delegates in liberal enclaves on the coasts and populist Midwest. Sanders, down but stubbornly not out, wins his home state of Vermont to add to his small trove of delegates from early states.

Videos by VICE

Four months of trench warfare have left four candidates with substantial delegate hauls — but no one won enough to lock in the nomination. As the Democrats head into their nominating convention in Milwaukee in July, they’re facing a nightmare that hasn’t happened since 1952: a contested convention.

There are four major reasons a contested convention is more likely to happen in 2020. A front-loaded primary calendar, crowded primary field, changes in superdelegate rules, and an increased ability for multiple candidates to raise serious money that could let them stick around longer in the race all raise the odds of a scenario like this occurring.

Indeed, some are already predicting it.

“I’d say 90% that it’s a contested convention.”

“If I had to bet money today based on what I know right now, I’d say 90% that it’s a contested convention,” said Leah Daughtry, the CEO of the 2008 and 2016 Democratic National Conventions.

To win the Democratic nomination, a candidate needs to win a bare majority of the delegates awarded from state party primaries. If no one has a majority, then the drawn out and damaging process of negotiation and dealmaking between candidates begins. If that happens on the convention floor, what’s supposed to be a well-coordinated coronation of the nominee could turn into a televised free-for-all.

“We hope that we’ll win it before that. It’s too early to speculate,” Bernie Sanders told VICE News as he walked from votes in the Senate basement.

READ: The Democratic Party is getting crushed in fundraising: “They need to get their shit together”

“I honestly haven’t given it any thought, to be honest with you,” Kamala Harris said with a laugh a few weeks ago before she ducked onto the Senate floor. “That’s so far down the line, I’m just trying to figure out how I’m going to make all my obligations for this weekend.”

Democrats haven’t had a contested convention since 1952, decades before they adopted an open-primary system in 1976. The closest modern-era analogies are 1984, when Walter Mondale needed superdelegates to put him over the top before getting thrashed by Ronald Reagan, and 1968, when Hubert Humphrey prevailed on the first nomination ballot after an acrimonious floor fight between delegates paired with anti-Vietnam protests on the streets doomed Democrats and elected Richard Nixon.

“We haven’t been through this drill in a long time.”

“We haven’t been through this drill in a long time,” said Illinois Sen. Dick Durbin.

Even Democrats skeptical they’ll have a contested convention say it’s at least as good a bet as picking any specific candidate right now. With nominal front-runner Biden sagging in the polls after a disappointing first debate performance, Warren rising at Bernie’s expense, and Harris surging, the race looks more wide open than ever.

Here’s why a contested convention is more likely in 2020 than at any time in recent history.

Front-loaded primaries

After voting too late in the 2016 primaries to have a real impact on either party’s nomination, California passed a law in 2017 stating its primary would be held on the earliest date allowed by the national parties, putting it and its 416 delegates on already-critical Super Tuesday March 3. By the time Iowans head to caucus, Californians will already have their early-voting ballots.

The Golden State isn’t the only state that’s moved up. There were 11 states voting and 807 delegates awarded last Super Tuesday; That’s up to 15 states, with 1412 this time around, fully 40% of all the delegates up for grabs in the primaries. Voters in those states will have little time after the first four primary states vote to figure out what to do since there’s almost no time to react after the first four states wrap up their voting.

The opening vote stretch in Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada and South Carolina wraps up on February 29, when South Carolina voters will head to the polls. That’s just three days before Super Tuesday, leaving little time and incentive for trailing candidates to drop out and making it harder for voters to rally around a front-runner.

READ: House Republicans are pressuring Amazon to sell books on gay conversion therapy

If three or four candidates are still winning delegates by then, it becomes mathematically harder and harder for any of them to win the majority necessary to become the nominee without a convention floor fight.

“California and other states moving to the front of the process — that has a significant impact,” said Frank Leone, a Democratic National Committee Rules Committee member from Virginia.

Sidelined superdelegates

DNC rule changes also increase the possibility of a contested convention — as does one longstanding difference between how Democrats and Republicans run their primaries.

As in past years, Democrats award all delegates proportionally rather than allowing winner-take-all primaries, unlike Republicans, meaning a state’s primary winner might get like one third or half of a state’s delegates instead of all of them. If the GOP had played by Democrats’ rules four years ago, Trump almost certainly would have faced a contested convention.

That means new rule changes might matter a lot more.

The most important change the DNC passed: Superdelegates can’t vote on the first ballot at next year’s convention. The rule change was made last year as a compromise between establishment Democrats and Sanders allies who see superdelegates as unfair to outsider candidates. Those elected officials and top activists have long played a role in helping front-running candidates secure the nomination. Blocking them from voting on the first ballot means it will be harder for anyone to win nomination cleanly

Too many candidates

That’s likelier to happen than in past years because of the historically crowded field. There are currently two dozen candidates, making it more likely that a few will have the momentum to win some delegates and money to keep running through Super Tuesday, making it harder for any one candidate to build up a head of steam.

A number of candidates will almost certainly drop out in the next two months as they fail to qualify for the fall debates and run out of money. And they’ll need to reach 15% in primaries to win delegates in any state or congressional district, a threshold that will keep other second-tier candidates from picking up delegates in the early states. Some skeptics think this will thin the field faster and lower the chances of a contested convention.

“If I’m not doing well in the first few states, I’m not going to stay in as some kind of vanity project,” said Rep Tim Ryan (D-Ohio), one of the candidates polling at less than 1%.

READ: Republicans won’t call Trump racist but one things white people are “people of color”

But it might make the actual primary process drag on even longer because a winnowed field makes it easier for the remaining candidates to top that threshold and keep winning delegates. Biden, Warren, Harris and Sanders are all over that threshold in many early polls.

The stronger candidates left standing will have less financial incentive to drop out even if they hit a speed bump. In years past, campaigns used to simply run out of gas if they weren’t gaining enough support ahead of the primaries, but online fundraising has made it easier for popular candidates to sustain themselves for longer.

Plentiful money

New DNC rules requiring tons of donors to qualify for the debates have pushed candidates to build out grassroots armies that could keep them in the race longer as well: 14 different candidates reached at least 65,000 donors before the first debates in late June, and it most of those appear to be on pace to meet the 130,000-donor threshold needed to make the September debates. Five different candidates raised more than $10 million in the last quarter — Biden, Harris, Sanders, Warren, and Pete Buttigieg.

“Most of the candidates with money… they’ll hang in through Super Tuesday, and they’ll have the money to do so. It used to be if you didn’t do well in Iowa you wouldn’t have the money,” said former Pennsylvania Gov. and former DNC chairman Ed Rendell, a close Biden ally.

Rendell said he still thought someone would be able to lock down the number of delegates needed, but admitted the changes had increased the likelihood of a contested convention.

“It’s more likely than it’s been in years and years,” he said.

The invisible primary

The campaigns aren’t eager to discuss their delegate operations — no one wants to be seen as angling for a contested convention win. But every one of them has top staffers focused on corralling superdelegates in case of a contested convention.

Harris has “Delegate Dave” Huynh, a veteran of a number of campaigns who led Hillary Clinton’s operation four years ago (“I’m very proud and excited about that,” the candidate told VICE News).

Biden has tasked Cristobal Alex, a top Democratic strategist who most recently ran the Latino Victory Project. Elizabeth Warren’s delegate counter is Brendan Summers, who served as Sanders’ national caucus director four years ago. Sanders’ 2016 delegate director, Matt Berg, is back for another round. Huynh’s partner on the Clinton campaign, Jeff Berman, got scooped up by Beto O’Rourke. Buttigieg was a late to the game, but in late May hired George Hornedo, one of Huynh and Berman’s 2016 deputies.

Superdelegates say they’re hearing just as much from the campaigns as in previous cycles, a sign the candidates think they might need them in Milwaukee.

There are plenty of skeptics who think the field will sort itself out.

“You’ll get more of a sense of how many candidates have the staying power, really, when they get into the fall of this year,” said Florida congresswoman and former DNC chairwoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz.

Money will force people out, and momentum could still push a front-runner ahead. Democrats’ best hope to avoid the potential catastrophe of a contested convention may be their fear of it. In poll after poll, voters say their overriding goal is to find a candidate who can beat Trump — and the prospect of a contested convention could scare them into rallying around a front-runner.

A handful of Democrats quietly fretted to VICE News that DNC officials aren’t taking the threat of a contested convention seriously enough, and worried that there aren’t procedures in place to help avoid hostilities that would further damage whoever wins the nomination.

DNC officials pushed back, even as they downplayed the chances of a contested convention. They’ve held hourlong briefings with every presidential campaign to lay out the rules, and went through states’ delegate nomination plans to troubleshoot potential problems at a recent rules meeting in Pittsburgh.

“We view the likelihood of a contested convention as being low. But we have processes in place,” said Patrice Taylor, the DNC’s director of party affairs and delegate selection.

Democrats disagree on the likelihood of a contested convention. But after a bumpy 2016 convention marred by pro-Sanders protests and Russian hacker attacks, most agree that if one occurs it would be a disaster.

“The convention we went through is nothing like what a contested convention would be like,” said Wasserman Schultz, who chaired the DNC then. “We’ve not seen [one] in modern times.”

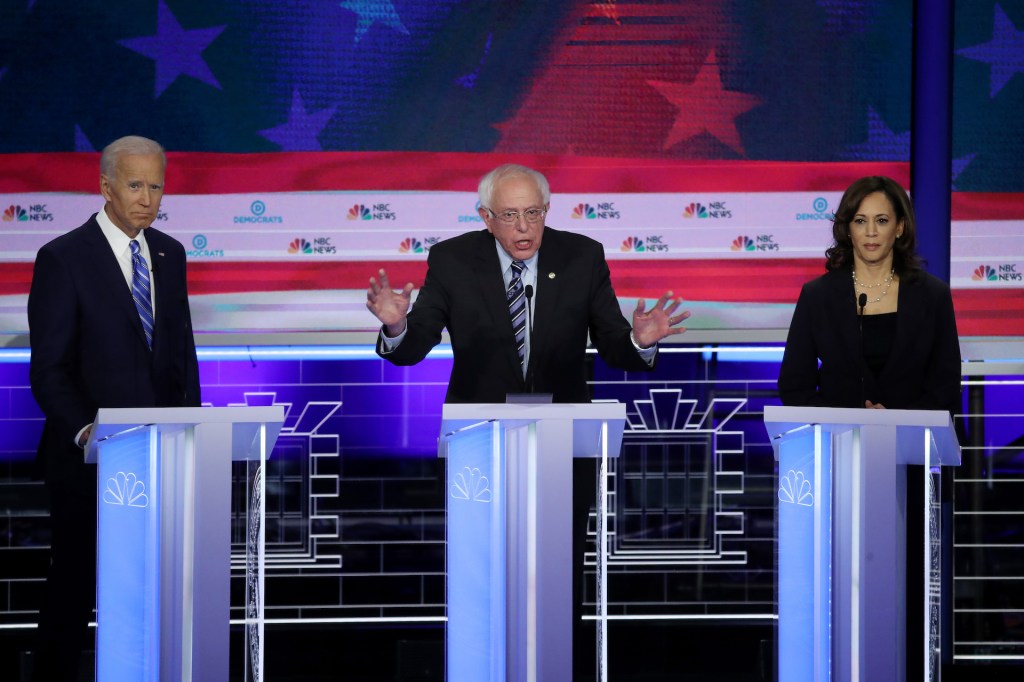

Cover: Democratic presidential candidates (L-R) former Vice President Joe Biden, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Sen. Kamala Harris (D-CA) take part in the second night of the first Democratic presidential debate on June 27, 2019 in Miami, Florida. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)