What’s it like to go around telling everyone you’re Jesus? I live in suburban Australia—which cult is right for me? The answers to these questions and more are in Your 2017 Guide to Cults and Fringe Religions

Late on May 28, 1993, the earth beneath the West Australian outback shivered. It was just a small rumble by geological standards, measuring about 3.6 on the Richter scale. As far as Geoscience Australia was concerned it was a fairly dull event, forgotten almost as soon as it was written down.

Videos by VICE

And things stayed that way until 1995, when—in the aftermath of the Tokyo Subway terrorist attack—West Australian geologist Harry Mason claimed the quake wasn’t an earthquake at all. It was a nuclear explosion, Mason said, conducted as part of a weapons test by the fanatical Japanese death cult behind the Tokyo attack with a homebrew nuclear device.

It was a fantastical story, but one that came with a disturbing degree of evidence.

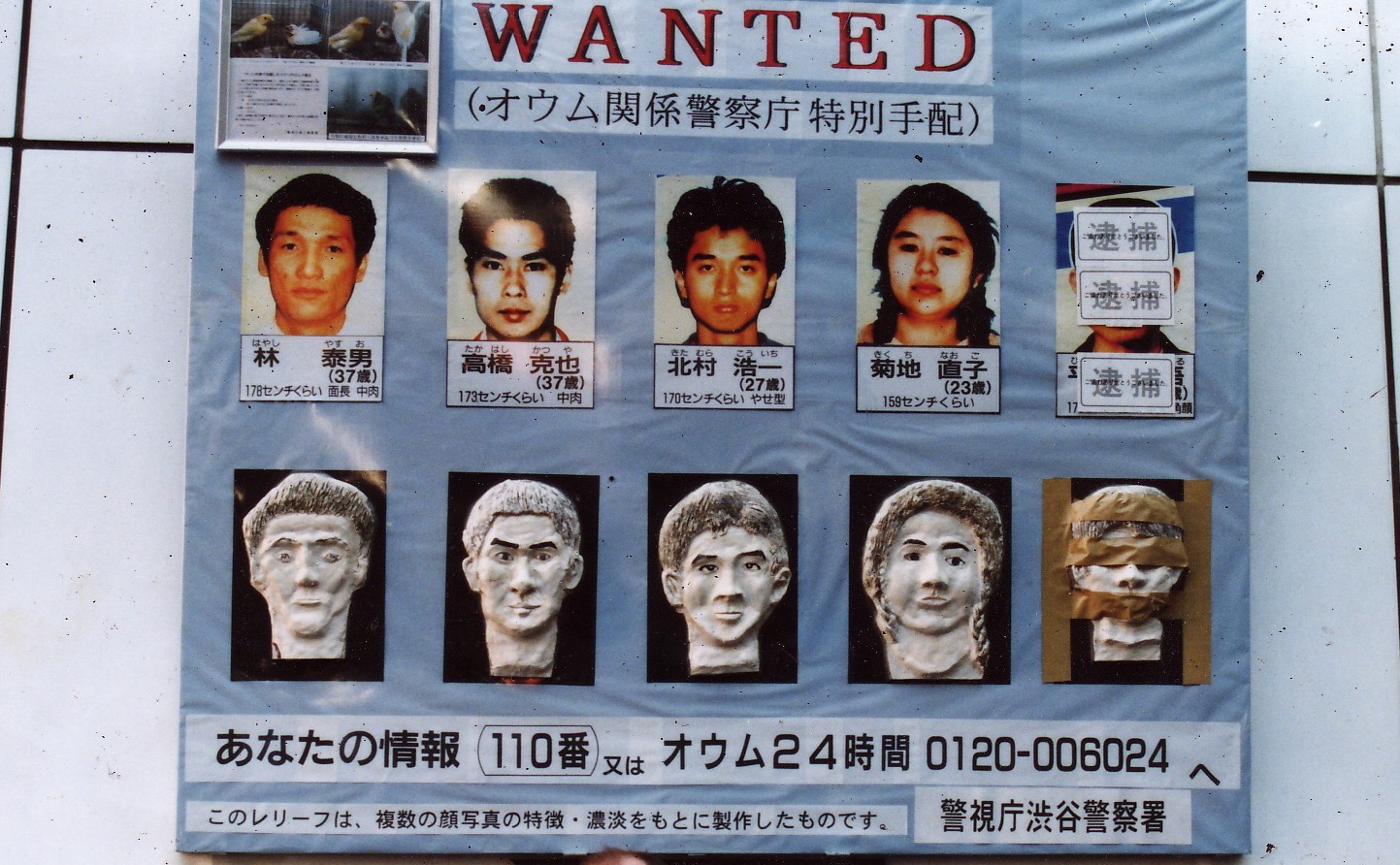

On March 20, 1995, members of a previously obscure Japanese religious organisation called Aum Shrinrikyo doused three lines of the present-day Tokyo Metro with deadly sarin nerve gas. Twelve people died, and at least 50 others were severely injured. In the ensuing scramble to figure out how the group, which had begun in a yoga studio, evolved into a terrorist organisation, it emerged that several members had actually spent most of the previous year in outback Australia.

Aum Shrinrikyo first came out to West Australia in April 1993, looking for a place they could test chemical weapons without interruption. An advance party had toured the region around Banjawarn Station, about 12 hours east of Perth. They ended up buying the property through a front company, and a small group of followers stayed on the station for about a year before selling the land at a loss and fleeing the country in October 1994.

And that could’ve been the end of the story. Until, in the wake of the Tokyo Subway attack, a world calmed after the fall of the Soviet Union found a new fear in the spectre of domestic terrorism with the potential for both chemical and nuclear weapons capabilities. And Harry Mason was only too happy to fuel those fears.

The notion that a cult had managed to cobble together a nuclear bomb, with no government assistance, while no one noticed, was wild. But the fact Aum Shrinrikyo had already committed a chemical attack lent weight to the threat, and captured the imagination of the New York Times and even the US Senate.

Something about it felt true. Aum Shrinrikyo had a billion dollar bank account, and members who’d previously worked in physics. And the Australian geologist making the claims seemed respectable enough, at least on paper. Harry Mason spent his professional life working in the mining sector, searching for gold right up until his death in 2014 from a heart attack while he was travelling in Vietnam.

To back his claims the 1993 event was no earthquake, Mason said he took a plane across Western Australia to collect witnesses statements—although these were usually anonymous accounts. Most talked about seeing a bright light in the sky, and feeling a shockwave. Initially, other pieces of evidence seemed to back up Mason’s claim. Like the presence of a high grade source of uranium on the 404,680 hectare station, which the cult had intended to mine (according to notebooks seized from one of its high-ranking members.)

The story soon made its way across the ocean, where it was picked up by US Senator Sam Nunn whose long involvement with anti-nuclear causes meant that even if it was unlikely group the had been experimenting with weapons, he had to be sure. Aum Shrinrikyo had already come to the attention of the US Senate Government Affairs Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. And Nunn pushed to expand its investigation to include the goings on in West Australia. That’s when the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology (IRIS) was asked to look into it.

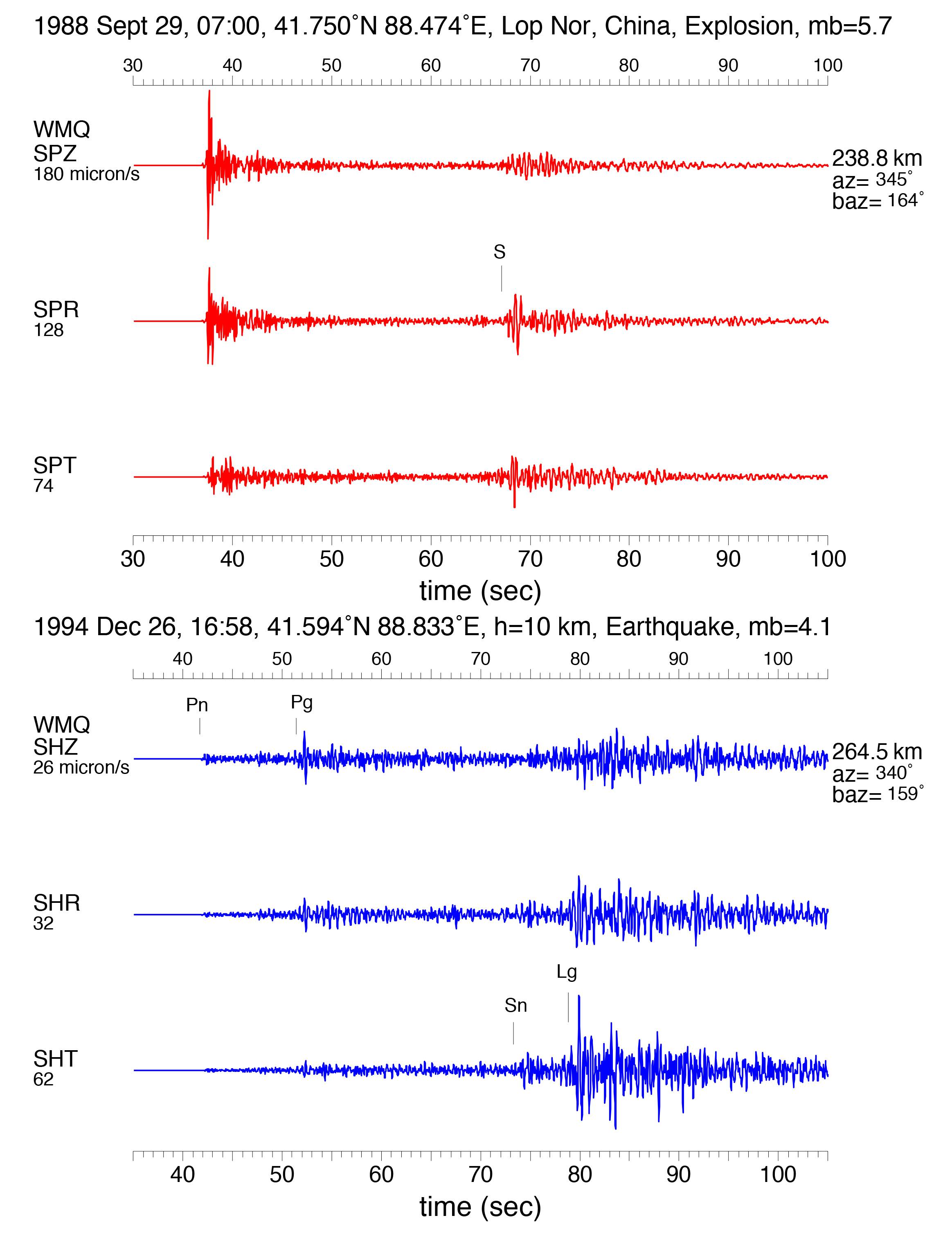

As an organisation, IRIS helps monitor compliance with the various nuclear weapons treaties that exist around the world, making one of its jobs to differentiate between earthquakes and nuclear explosions. Back in 1996, IRIS’ director was Dr Gregory Van Der Vink, a professor of geology at Princeton University. When Van Der Vink investigated the seismic activity around Banjawarn, he found no evidence of a nuclear blast.

“If I recall correctly, it was a rather unusual seismic recording,” Dr Van Der Vink told VICE. “Although it was not a nuclear weapons test. The seismic signal was not characteristic of the type produced by explosions. As you can imagine, explosions create pressure outwards in all directions, whereas earthquakes and a surface meteorite impact have a shear component associated with them.

“The epicentre was also very shallow, near or at the surface, so it was not characteristic of an earthquake either. Our first choice wasn’t to claim it was an earthquake. But when we ran the numbers on probability, it seemed like a reasonable explanation that could explain all the data.”

If the tremor was indeed a meteorite strike, it could’ve been similar to the 2013 Chelyabinsk meteor, which exploded over Russia, delivering a shock wave that injured 1,200 people. However Dr Van Der Vink says it’s more likely the 1993 event was just a regular meteorite strike, which could’ve been confirmed by the presence of an impact crater. But such a crater was never found.

At least in part, this may have come down to the fact that the desert region around Banjawarn is about the same size as the UK. And although there was a plan to enlist legendary geologist Gene Shoemaker in the crater search, he was killed in a head-on collision in Alice Springs in July 18, 1997.

“Both a shallow earthquake and a meteorite impact could create the surface waves seen in the seismogram. Either of these events would be unusual,” said Dr Van Der Vink. “So choose your unicorn.”

As investigators probed deeper into Mason’s theory, they found it didn’t stack up for a range of reasons. When the Australian Federal Police visited Banjawarn Station, there was no evidence of uranium mining on site. Although they did, to no one’s surprise, find chemicals the group had been testing out on the sheep population. On top of that, the chronology was off. It was only a couple of weeks between the purchase of the property by the cult and the earthquake, and the first Aum Shinrikyo followers would only turn up in Perth on September 3, 1993.

None of this deterred Harry Mason though, who stepped into the void of information and expertise as the local expert—or crank, depending on your perspective. In the role, he soaked in the press attention, including a cringeworthy BBC documentary feature. It was rumoured that during production, Mason paid the participants $300 a day to take part in the reconstruction scenes to boost his credibility by implying there were other witnesses. When Mason fronted the camera, his story expanded to suggest that the quake wasn’t caused by a backyard nuke at all, but some kind of tectonic weapon of the kind Nicola Tesla once boasted about—a common conspiracy trope that has been debunked several times over.

So, it was all bullshit. But Mason was an artist at the craft. To this day, his ghost lives in the backwaters of the Australian internet, where the text of his “investigation” is preserved online and wherever videos of him talking about his theories appear on YouTube channels whose owners also post videos about Reptilian alien infiltrators.

And it’s this story that’s interesting. Not the one about government conspiracies and clandestine nuclear tests, but the other one about a guy who blagged his way as far as the US senate, and who, for a brief moment, held the attention of the world long enough to find some measure of immortality as the hero of an urban legend.

Follow Royce on Twitter

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Xbox -

Screenshot: Sony Interactive Entertainment -

Screenshot: The Game Awards