A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

The big-box technology store isn’t dead yet—and in the case of Best Buy, it’s actually doing pretty well, beating financial estimates by a country mile.

Videos by VICE

But as a whole, the concept of the sprawling electronics chain is far from its peak. In fact, it’s sort of another shade of the office-supply store.

Despite that, investors keep trying to revive this idea. Right now, an investor named Ronny Shmoel is trying to bring Circuit City back to life as a physical presence, roughly seven years after the brand was mothballed.

These stores have traditionally been pretty huge, somewhat faceless, and built with the same philosophies that defined selling appliances in the 1960s.

(To put some numbers into the equation, the average Best Buy is 37,000 square feet, according to an estimate reported by The Star-Tribune in 2012. That’s relatively small compared to the average Walmart SuperCenter, which takes up 179,000 square feet. Both Walmart and Best Buy have been experimenting with smaller formats so as to hit different markets.)

Here’s my question about all this: Does the format really make sense at all? When it comes to selling electronics, can we do better? That’s a tough question; here’s my attempt to unpack it.

The tale of DIVX, Circuit City’s horrible alternate-universe Netflix competitor

In 1997, Circuit City was perhaps at the peak of its powers as a retail chain, and it was in a position to help shape the way we used technology.

Problem was, the chain’s big foray into the world of hardware production was horrifyingly inept, driven by film-industry interests, and put into place in partnership with a law firm. A law firm!

(That law firm, Ziffren, Brittenham, Branca & Fischer, is one of Hollywood’s most powerful, by the way.)

But that 1997 announcement of Digital Video Express, or DIVX, was an attempt to reshape the home video industry in a way most beneficial to the movie studios. The strategy, based on the then-new DVD technology, involved the use of encrypted discs that can be used over a short period of time, but become re-encrypted after the availability window ends.

“The DIVX disc is never returned, and so the consumer never has to pay late fees. The disc becomes part of the consumer’s home video library, with additional viewing periods easily purchased through the Divx player,” a 1997 press release explains. “Consumers also will be able, through the player, to convert many titles to unlimited viewing for a one-time fee, and certain titles will be available for purchase in the store as unlimited viewing discs.”

Almost immediately, the idea took on a level of hatred that could only be compared to the way that some people talked about Internet Explorer back then. A number of anti-DIVX sites soon showed up on the scene, with passionate screeds that earned notice in the mainstream press.

John Giberson, a Texas resident, earned media notices by launching the “National Organization to Ban DIVX” soon after the platform’s announcement. So assured was he that everyone else would dislike the idea of DIVX that he simply linked to Circuit City’s website and told his readers to get informed.

“[DIVX] makes early adopters of DVD mad,” Giberson told the South Florida Sun-Sentinel in 1998. “I think it’s a bad idea and so do about 500,000 other people that have hit my Web site. I want to see DVD take off and stay as an affordable product for the mass market.”

Giberson and other voices soon helped set the conversation, helped along by the fact that Warner Bros. and Sony both opposed the format. Additionally, once you broke down the value proposition, it was clear that buying a DIVX disc wasn’t as good as going to Blockbuster, made problematic by an unforced error on the studios’ part: They didn’t include any of the DVD extras on the DIVX discs, and worse, panned-and-scanned everything, meaning that the integrity of a DIVX offering couldn’t compare to standard DVDs.

Image: Mike Kalasnik/Wikimedia Commons

Another factor was simply logistical: Circuit City was the only firm selling DIVX throughout most of its life, and Circuit City was a big-box store. It generally wasn’t as close to your house as the average Blockbuster was, and its hours weren’t quite as good, either.

But the biggest problem was that it cost Circuit City a lot of money, and that’s what did it in. In mid-1999, the DIVX debacle was shut down, with Circuit City having dropped $233 million in the hole with little to show for it beyond a lot of angry customers.

Oh, and this training video. They got a training video out of it.

It’s just one example of the problems that arise when you treat electronics like appliances.

How CompUSA’s treatment of Apple fans shows just how poorly suited the big box is for technology

In 1997, Apple was on the ropes, and needed a new distribution deal to get its products to the public. It went to the arms of a partner that it was familiar with.

But ultimately, the lessons it learned from the experience led the computer maker to forge its own path.

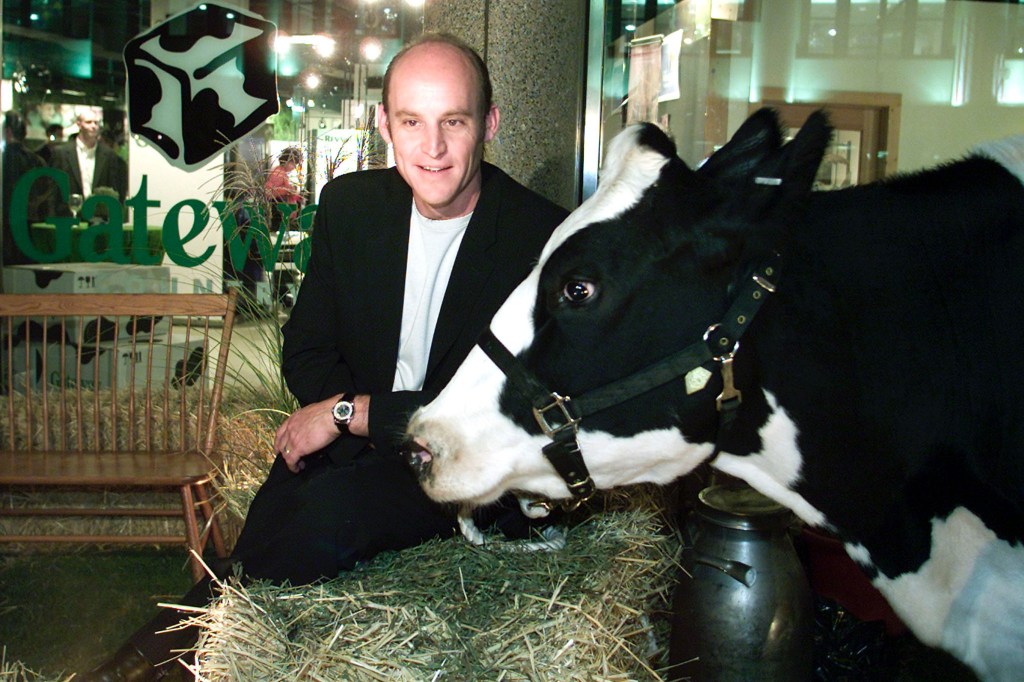

In 1997, the tech superstore CompUSA agreed to create a store-within-a-store concept for Apple, allowing the company to put a sales rep on the floor who could properly help Apple’s own customers make decisions.

“We believe in the future of Apple, and we are making a large investment to show our recommitment to Apple,” CompUSA President and CEO Jim Halpin said in a press release at the time. “These specialized departments within our Superstores will offer a superior buying experience for the Apple customer.”

Problem is, Halpin’s concern apparently wasn’t communicated down to individual employees. The Apple enthusiast site MacsOnly ran a page charting various consumer experiences at CompUSAs around the country, and there were a lot of situations where the staff didn’t really understand the platform. Understandable, to a degree, because it was during a period when the Mac had slim uptake. But not for a company that was supposed to be actively promoting Apple.

Image: FIshstick/Wikimedia Commons

Even famed technology columnist David Pogue, then a writer for MacWorld, had trouble. He went to half a dozen locations around the country, dealing with CompUSA employees at each location who seemed to have little to no interest in selling Mac-based hardware or software.

“Whatever the excuse, CompUSA simply isn’t holding up its end of the sweet Apple deal,” Pogue noted. “In steering potential buyers away from Macs, store clerks make a mockery of CompUSA president Jim Halpin’s 1997 promise to make his stores ‘the Apple headquarters for America.’”

So no, Apple couldn’t even get a decent presentation from a big-box store, so it eventually started looking into its own retail outlets. Those outlets, smaller and more specialized, did the job much better than a big box ever could.

The ceilings are nowhere near as high, either.

“Stores will still be necessary to sell products and services and to teach people how to operate in this new digital civilization.”

— Carlos Slim, the Mexican billionaire, discussing his 2000 purchase of CompUSA for $800 million. Despite that seemingly sound bet, CompUSA faltered by 2007, with Fortune characterizing Slim’s ownership of the firm as “a rare misstep” for the world’s richest man at the time. Turns out, stores apparently weren’t necessary.

When CompUSA closed its doors in early 2008, becoming one of many chains that have liquidated over the past couple of decades, the company gained a bizarre reputation on consumer blogs for attempting to sell products that did not work.

The Consumerist, then owned by Gawker Media (which did not have a liquidation sale), kept an eye on the bloody toll. DVD players that were labeled “defective,” were being sold for $179.98. Shattered LCD screens, despite being no good, were sold anyway. People, attempting to buy stuff with cash, were turned away by store staff.

In some ways, I wonder if the model for the computer superstore deserved to be left on the shelves in liquidation.

These stores happened to grow into the behemoths they did not just because the computer industry grew, but because, in many ways, they were competing with every other type of retailer. Bed, Bath, and Beyond has huge stores, too; so does Michaels, IKEA, and even Old Navy. Computing as a medium is simply too mainstream, and a tiny Radio Shack store wasn’t going to cut it.

One problem, though: For decades, people who sold computers never really figured out what the retail model wanted to be. Does it want to be built around heavy customization? Does it want to be an intensely personal experience? Should you get the chance to touch the device you’re about to buy, or are you better off just grabbing it in the mail after the fact? Should salespeople be up in your face or should they get completely out of the way?

It took probably 20 years to get a reasonable answer to most of those questions.

But big-box electronics retailers had to start somewhere, and rather than treating gadgets like some of our most important possessions, retailers long sold them like just another appliance. Computers are not washing machines—we work with them far too intimately, and we shouldn’t sell them the same way. The fact that computers are built through the same sorts of industrial processes that make washing machines must have confused someone down the line.

With their boutique stores, Apple, Microsoft, and other big tech firms have figured that out. And even if the context is all wrong, it doesn’t mean the success of an electronics superstore isn’t possible: Best Buy is doing OK right now, but for a while, it was looking pretty shaky.

Sure, Amazon could still eat their lunch—they’ve done it before. But I wonder what a totally rethought Best Buy would look like, unshackled from its roots as a stereo retailer.

Like the devices they sell, electronics retailers can occasionally use a reboot.