There’s an iconic scene in Jurassic Park depicting the “birth” of a baby velociraptor in a laboratory nest. Defenseless and adorable, the newly hatched predator is cradled by the characters as they ask the park’s staff about its engineering and physiology.

But there’s one question the film conveniently leaves out: How long are these dinosaur embryos incubated before they break free of their shells? Do they hatch quickly, like modern birds, or do they take several months to develop, like modern reptiles?

Videos by VICE

For the purposes of a blockbuster monster movie, the answer is pretty much irrelevant. But for real-life paleontologists, who don’t have the luxury of handling resurrected dinosaur babies like their fictional counterparts, estimating incubation periods has been a persistent mystery due to the sheer scarcity of embryos in the fossil record.

“They’re really cute. Unfortunately, they’re dead. But they’re really cute.”

“Dinosaur embryos are the rarest of the rare,” said Gregory Erickson, a paleobiologist and professor based at Florida State University, in a phone interview with Motherboard. “There’s a very small window [for preservation]. Somehow, the fossilization environment has to percolate down and get minerals to the bones to fossilize them.”

It’s an improbable scenario, but the fossil record does occasionally offer up some stunning embryonic specimens. New research published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, led by Erickson, focuses on two such examples at very different scales.

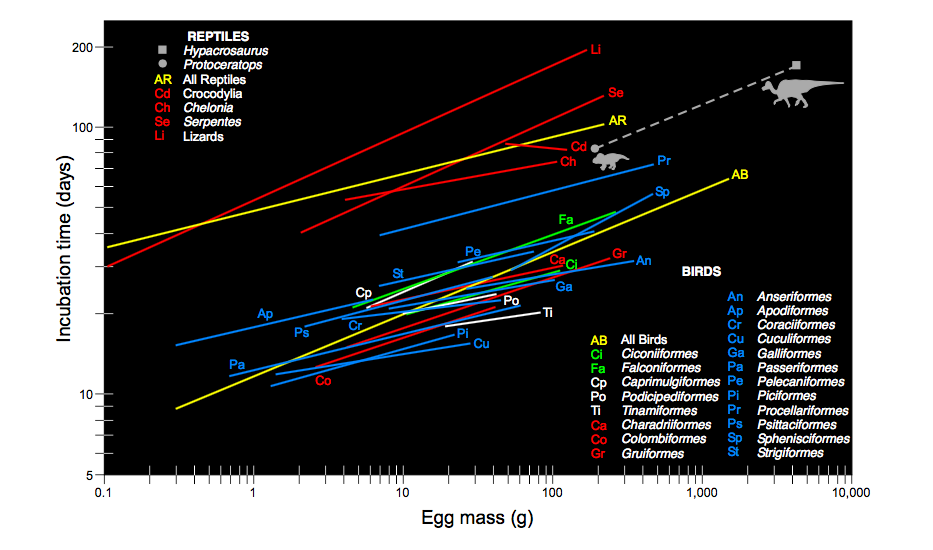

On the featherweight end of the spectrum, the team studied the embryo of a sheep-sized species of horned dinosaur called Protoceratops, fossilized within an egg estimated to have weighed about 194 grams. An embryo of the duckbill dinosaur Hypacrosaurus, encased within a volleyball-sized egg weighing four kilograms, was the heavyweight of the paper. This dinosaur would have been almost as large as Tyrannosaurus rex had it hatched and grown to adulthood.

READ MORE: Parenthood in the Age of Dinosaurs

“They’re really cute,” Erickson said of the little dinosaurs “stuffed in” their fossilized eggs. “Unfortunately, they’re dead. But they’re really cute.”

It gets cuter. Like some Cretaceous riff on the tooth fairy, Erickson used the novel technique of extracting the embryos’ tiny baby teeth to examine the incremental lines of growth laid down during their dental development. The method is analogous to approximating a tree’s age by its growth rings.

“These are the smallest dinosaur teeth I’ve ever worked with,” said Erickson, who has worked on a variety of fossilized dental records. ” It was like trying to section a pebble.”

Daily growth lines in the dentine of an embryonic tooth of Hypacrosaurus. Image: G.M. Erickson

The work paid off, and the team was able estimate the length of each incubation period: Protoceratops likely hatched after about three months, while Hypacrosaurus embryos hatched after nearly six months.

The results provide “some of the first empirical insights into dinosaur embryology and life-history strategy,” according to the paper. The findings also buck the commonly held assumption that dinosaurs had short incubation periods, like their avian relatives. While birds live their embryonic life in the fast lane, hatching within 11 to 85 days, dinosaurs appear to have been much more slow-growing, akin to modern reptiles.

Graph depicting the relationship between incubation time and egg mass across reptiles, dinosaurs, and birds. Image: Erickson et al, PNAS

This discovery is crucial to reconstructing dinosaur life cycles and behavior. “There’s myriad implications,” Erickson told me. “Once you know the incubation period, it’s like a lynchpin. It allows you to address all kinds of questions. We know this from birds and reptiles today.”

For instance, the slow embryonic growth of dinosaurs helps explain why they tended to lay large clutches of small eggs. Long incubation periods put offspring at greater risk of being killed by predators, or by natural disasters like floods or droughts, so dinosaurs may have hedged their bets by laying many eggs to offset heavy offspring losses.

The paper also sheds more light on why dinosaurs were wiped out by the K-Pg extinction event 66 million years ago, while many birds and mammals flourished. Dinosaurs invested so much time and energy into incubating their broods that they were easily outcompeted by smaller animals with shorter generational turnover.

“We think that dinosaurs found themselves holding some bad cards,” Erickson said. “They were basically holding a dead man’s hand; black aces and eights. They had some physiological and life history attributes which were not conducive to survival in the K-Pg cataclysm.”

The research provides a new roadmap for reconstructing the embryonic growth of animals that lived millions of years ago. Erickson also anticipates that the incubation periods of other fossilized embryos, from dinosaurs to mammals, could be analyzed the same way.

“This is why we need to go out and dig out more stuff,” he said. “There’s a lot more to learn.”

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.