Most of the world’s great companies have a good creation myth. Nike was started from the trunk of Phil Knight’s car. Apple, Google, and Amazon all started in a garage. Discogs—the music cataloguing database and marketplace founded in 2000 by Kevin Lewandowski—has a similar, albeit more cramped origin story. It started in a closet.

“I was living in an apartment building at the time that provided free T1 internet access, so I talked to management and they said it was fine,” says Lewandowski, Discogs’ 42-year-old founder and CEO, during a video call from the company’s headquarters in Portland, Oregon. “At one point, the server actually moved into the apartment manager’s closet. He accidently kicked out the power cord once. Eventually I moved it to some place more stable.”

Videos by VICE

17 years later, Discogs’ office is more akin to your typical tech start-up, with arcade machines, pop art on the walls, and a full DJ booth set-up, equipped with an in-house record collection. While they don’t sell phones, search engine results, or sneakers, they’re a market leader in their own space: categorizing, archiving, and facilitating the sale of records—plus the occasional CD, cassette, or DVD—via a crowdsourced community of loyal users.

Discogs’ in-office DJ booth.

Curious who cut the lacquer on Daft Punk’s seminal Discovery album? Looking to shell out $15,000 for a rare Prince album, like one buyer did last year, topping the company’s annual sales report? Discogs is the place. Since the company’s inception, users have built one of the most comprehensive and awe-inspiring music databases in human history.

Discogs is showing no sign of slowing down. In 2016 alone, their database grew by 12%, bringing their total number of listings up to over 8,000,000; it was also a record-breaking year for sales, with 6,691,144 vinyl records sold, and a 26% increase across formats. According to the company, some labels even refer to the company’s annual report to figure out what records from their catalog are worth repressing.

That said, using the service can be daunting. Those selling or entering discographical data on a piece of music—known in Discogs-speak as a “submitter”—must adhere by a strict set of guidelines dictating how to rate the quality of your music using the Goldmine grading standard. (Sellers are also charged an 8% fee on every purchase). Buyers, for their part, have an overwhelming number of musical titles to sift through—an oft-dangerous realization for one’s bank account and personal sanity. Users feeling a little tentative can place a title on their wantlist to monitor price fluctuations, or just leave it in their cart until they’re ready to buy—with the caveat that someone else might buy that record first.

While you can pick up everything from a Japanese pressing of a Rolling Stones album to the new Rihanna release on Discogs, the company began as a destination of dance music. Or, more accurately, as one for deep, dance-music loving collectors—the types of heads who will pay $80 for three tracks from Detroit house producer Andrés, whose 2012 EP, New For U, was the number-one seller site-wide in 2013. The Andrés’ record sold a whopping 500 times that year, so you can get a sense of how many people are paying top dollar for music your average music consumer can’t ID. “There’s a massive long tail of all kinds of stuff that nobody’s ever heard of,” says Lewandowski.

Not surprisingly, some of the early team members, like Scotland’s Nik Kinloch, are house and techno heads themselves. After a stint working at a Detroit ghetto tech label, Nik—an early user of the site—emailed Lewandowski to express interest in joining the team in 2002. He’s been the Director of Product ever since, and his organic entry into the company speaks to their perennial crowdsourced vibe.

In the decade to the come, the staff would expand to include folks like Chad Dahlstrom, a former employee of independent music distributor CD Baby who became COO of Discogs in 2014. By that point, Discogs had opened up its doors to nearly every music genre in existence. Ron Rich, who cites his most cherished record as a first pressing of Radiohead’s Kid A—scored on Discogs, of course—came on board a mere two years ago, as Head of Marketing. Discogs thrives on file searches—people who have a very specific record in mind and either want to learn about it or buy it. For that reason, the company didn’t need marketing for years. Their product literally sold itself.

Discogs Founder and CEO Kevin Lewanndowski (left), Chad Dahlstrom, COO (right)

Nowadays, Discogs has an app that you’ll often see people use to look up the “going market rate” of vinyl they find in record shops—often to the chagrin of cantankerous record store owners. (Like most of their updates over the years, it was requested by the users). They also recently acquired an ongoing event series and record fair, where the world’s best selectors play amidst buyers and sellers, and continue to fascinate music lovers with a variety of awe-inspiring sales numbers. In the below extended interview, we spoke with Lewandowski, Dahlstrom, Rich, and Kinloch about the company’s fascinating evolution from a barebones haven for data-obsessed techno heads to an industry behemoth.

THUMP:Kevin, I read in the New York Times that you started the company mainly as a way to categorize your own techno records. How did your affinity for record collecting play into the creation of Discogs?

Kevin Lewandowski: I was in my last two years of college when I started buying records. When I graduated, I bought turntables and started spinning. This was around the late 90s—before they had web forums—and I was on a couple music mailing lists where I’d ask questions about stuff like back catalogs or artist pseudonyms. All that information was just exchanged manually over email, kind of like what happens in record shops. There had been talk [among mailing list users] about an online database for this information. People were talking about creating a project called Trainspotter, which was supposed to be this amazing, cross-referenced music database. It actually part of a project called Hyper Real, a rave archive site. If you went there, you would go to the discographies section, and there would be these microsites.

They tried for around three years to build [Trainspotter]; looking back, it had the classic problem of too many people involved—with too many opinions—and not enough doing. But the idea really excited me, and I had a software background and had been writing code since high school, so I was interested in creating something. I took a stab at it and built something very simple. I took about six months, and then, in late 2000, I launched [Discogs].

Besides Trainspotter, were there any other sort of discographical websites that you knew of?

Lewandowski: There was another website called Amazing Discographies. It had discographies of lots of labels, but you had to email the owner of [the website] and send him submissions and he would add them. They didn’t have detailed tracklistings or anything. Otherwise, there were a lot of specialized artist discographies. I know there was a big one from Moby.

What were some of the company’s early milestones that stand out for you?

Lewandowski: Traffic was initially very low, but it was almost doubling every month around 2001-2002. I wasn’t happy with my job at Intel, and realized I couldn’t be there much longer, so I gave myself around six months. A little bit later, they offered voluntary severance to my group, so I’d be able to get about six months’ pay to resign. It was a pretty easy decision. That was a big turning point; it gave me a lot of time to focus on [the company].

Then Discogs went through a lot of iterations—figuring out how to make money, and struggling with how to [evolve] it from an underground collector thing into a business. I did a premium member service where you could pay around $12 a year to get advanced features, then turned that off a couple years later; it wasn’t too popular. When Google AdSense came out, that immediately provided like $3,000 a month, which was what I needed to pay all the bills and break even. It took about nine months to get to the self-sustaining point. When we launched the marketplace in late 2005, it was pretty clear within the first year that it was going to be big, and that that was where I should focus revenue-wise.

When we launched the marketplace in late 2005, it was pretty clear within the first year that it was going to be big—Kevin Lewandowski, Discogs Founder and CEO.

What prompted the creation of the marketplace?

Lewandowski: The users asked for it. There was already a “collection” and “want list” feature, and a lot of people asked for a “sell” list, just to have a list of things that they were selling. I also noticed that there was a lot of buying and selling going on behind the scenes through private messages and email. People had even created accounts with interesting names like “everything in this collection is for sale” and had hacked the rating system to indicate price. So if it’s 5 out of 5, that’s $10. 4 out of 5, that’s $8. People wanted a way to buy and sell records. Amazon and eBay were around, but they weren’t really what they are today.

How were people finding out about the company back then?

Nik Kinloch: The community was purely an online thing—everyone kind of met on Discogs, and they were all very, very invested. I think our users are still really invested in the notion of Discogs, of cataloging all this music that everyone loves, and sharing that. A lot of the traffic was people searching and finding things.

Char Dahlstrom: File searches.

Lewandowski: It was total organic traffic. We never even had marketing until [Ron] got here a couple years ago. All of this content is so unique, and there’s not many other places where you can find it.

Kinloch: I think another really important thing that happened was when we moved from having just electronic to all these other types of music. It took a few years to actually add all categories of music. I think that probably lined up with the start of the marketplace, when we finally had everything.

Lewandowski: I put that electronic restriction in place in the beginning because it was just overwhelming not to, and because technically, it’s much more difficult to catalog jazz and classical. The structure of the information [in electronic music] is much simpler. I think that’s probably one of the reasons why Discogs got off the ground and Trainspotter did not: they were aiming for this bigger project, and we had a much smaller focus.

Discogs’ headquarters in Portland, Oregon.

Did you notice the type of people using the site change as you opened the site up to more genres?

Kinloch: It wasn’t that huge a shift to go from electronic to rock. I think people do like music across genres. [Discogs] has kind of lost a little bit of that cliqueness, which honestly, I think is good. It’s like, “Yeah I just like Swedish techno, and don’t listen to anything else.” That mentality gets a little stale after a while.

Lewandowski: Electronic music was our core for two solid years. That created a base of users that were interesting, and who expanded the database [based] on their tastes. People that are into electronic also might like industrial for example, which gets into rock. Rock took over last year; [Fleetwood Mac’s] Rumors] was our top seller, and then [Pink Floyd’s] Dark Side of the Moon. A couple years before that, it was Lazaretto from Jack White. So yeah, there’s sort of been a shift where rock music has taken over from electronic as the bedrock of our sales.

Dahlstrom: There’s certainly new challenges—you get grindcore [ laughs], you get stuff that you can’t unsee. We’ve certainly taken a stance where, at least from our perspective, if something’s hate-filled or offensive, we won’t allow it to be sold. Like white supremacy—you see [music that crosses] the line, and that’s the kind of thing we don’t really want to profit from. It’s an archive, it happened; we do the database thing, so everything that happened is in there.

What role has discogs played in the evolution of vinyl?

Lewandowski: Discogs has grown every year, so along with that rise in the interest in vinyl, we’ve continued to [grow] as well. I think where we fit in is not in mainstream music, and more the collector’s’ sense. When people want to dig deeper and learn more about the obscure producers on those records, that’s when they go to Google and discover Discogs, and start buying rarer stuff.

Dahlstrom: It is the reason why there’s 50 people here now instead of 16. People have asked us what our place in [the vinyl market] is. We’re not producing it—it’s the market that’s decided they want it. But I’d say we were kind of a steadfast part of keeping it alive.

I’d say we were kind of a steadfast part of keeping [vinyl] alive. —Chad Dahlstrom, Discogs COO.

Do you think this mass trend of major labels pressing records is a bubble?

Dahlstrom: We think about this a lot. Repressing is certainly part of it, but then you look at the indies and you look at how many people are using record pressing plants, and how busy they are. I can only predict so far, but things seem to be still heading in the right direction. We were just in the Netherlands where people are converting CD presses into record presses. Overall, the [vinyl] industry is engaged.

What kind of relationship do you have with labels?

Dahlstrom: We talk to the labels a lot. I was at a San Francisco music tech conference once talking to a guy from Warner/Atlantic, and he said that they use Discogs to look at their back catalog instead of their own internal catalog. We just hired this guy Jeffrey Smith, who has been a music promoter for 15 years, to build those relationships more. We want the labels to be involved. We want our data to be accurate. If they want to sell through us, that’s great, too.

Lewandowski: Yeah, [the labels] all use Discogs. But we’ve taken the stance that we’re not gonna do any bulk catalog imports.

Dahlstrom: From [a label’s] perspective, we’re kind of a cornerstone of the vinyl market. If I were them, I’d way rather sell an LP than [stream it], because obviously they’re going to make more money per unit that way.

Ron Rich: The data’s right there. A lot of the labels can go in and look and see an artist’s most collected release, most wanted release. So the labels will come look at that data to decide which records they want to repress.

Price-gouging is a topic that comes up a lot when talking about Discogs and the vinyl market. Have you guys learned to manage that, if at all?

Lewandowski: I’ve heard theories that Discogs want to jack up prices and all sorts of things, but we’re 100% hands off with pricing. Dealers can price things for whatever they want, and buyers can decide what to pay.

Kinloch: Pure capitalism.

Lewandowski: It’s an open market.

Dahlstrom: I’m not going to name names, but some other marketplaces will see a product that’s selling a lot and they’ll go produce it themselves, and they’ll change the price, and maybe ship it directly for free. We’re not doing any of that. We’re not taking the data and influencing the market in any sense. Furthermore, record stores go online and start pricing directly from Discogs. Has somebody gone in a record store with the [Discogs] app and been like, “I can buy it on discogs for this, so what am I doing here?” And do record stores sometimes get pissed about that? Sure. We have a platform. But do we have any influence over it? No. It just does what the market does.

Lewandowski: The biggest complaints I’ve seen about pricing on Discogs are often from sellers or buyers who want to buy something cheap and flip it for a lot of money. Or sellers who can’t get the deals that they used to get, because the pricing is out in the open now.

How often do you see inexperienced buyers using Discogs, as opposed to more serious record collectors?

Lewandowski: The majority of our traffic is just people lurking. There’s 10 million people visiting the site every month, and we have 3 million users.

Rich: It’s a rabbithole. Someone might come in to see what Dark Side of the Moon’s all about, and next thing you know, they’re looking at anything else that [David] Gilmore’s touched. So, in terms of that barrier for entry, it’s sort of a choose-your-own-adventure at that point, right? There’s nobody over your shoulder barking orders at you, but there’s also no one there to hold your hand.

Kinloch: It takes a bit of knowledge to submit and even just to understand the site, and we’ve got pages and pages of help docs on how to enter data. It’s a real labor of love for people to do that. But what makes Discogs amazing is that people have the passion for that data, that they’re actually going to sit down and dedicate their time to building the site. We’ve got over 8 million releases in there; I think we’ve got more pages than Wikipedia now.

Lewandowski: It varies from people wanting to be mentors, to curmudgeons that get upset when you [enter the information] in wrong. The lead submitter actually works for us, and part of his job is coaching and trying to get people out of the “I submitted something wrong and I never want to touch [Discogs] again” mentality.

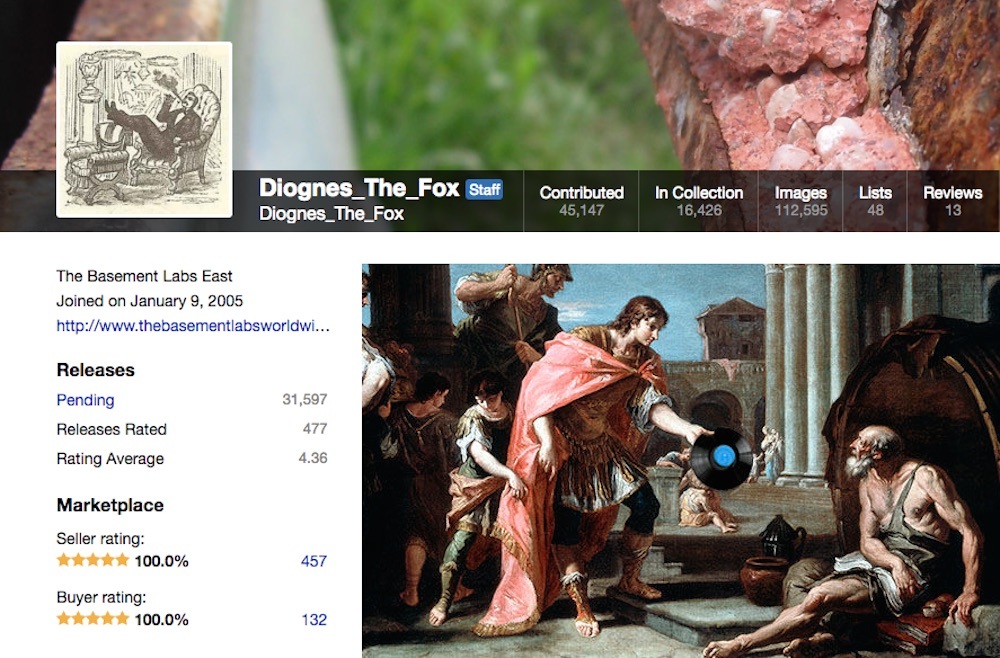

Who’s the lead submitter?

Lewandowski: His name is Brent. His username is Diogenes the Fox. I forget how many submissions he’s done. 30,000, maybe? I was having a conversation with someone a while ago about our strangest and most obscure records. I think mine was this one called “Sounds of Steam”; it’s just recordings of steam locomotives from the 50s. So I look it up, and sure enough, it was submitted by Brent.

Dahlstrom: There’s kind of this altruistic mentality with him. Like, if this album doesn’t get recorded in this database, did it happen? He’ll get weird and go buy these collections of aerobics records from the late 70s.

What are some things Discogs has coming up?

Lewandowski: I’ve also been focusing on what we call our meta-projects. LIke applying the Discogs concept to other things. We’ve started [a music gear database] Gearogs, because gear is so close to records. We’re launching a marketplace in April.

Dahlstrom: Again, we asked the community, who said, “We love the way [Discogs] catalogs stuff; we want to catalog these things too.” We also bought the Crate Diggers project, so we’re trying to do more of the record show stuff—getting out there and talking to people. We want to keep that alive, while trying to create our own version of it. We’ve all been to a record show in a church basement, and there’s nothing wrong with that, but we’re trying to just celebrate that concept of live buying and selling, and getting into those genres and those areas worldwide where we don’t have a lot of music. How complete is our J-Pop section? How complete is our Cuban jazz section? We’ve got the site in more languages, and we’re open-sourcing the translations as well.

Kinloch: Another piece of the puzzle is the data side of things, and how we can show people data in different ways. We have all of the releases with the tracklistings as just plain text. They don’t do anything. So what we’re trying to do is to promote the first class data so we can link together tracks, look into that musicology of where they came from, who wrote them, what other versions are there of the tracks. How they’ve changed over the years, how they’ve been remastered—all that kind of metadata. We haven’t figured it out fully yet, but there will be over a hundred million tracks in our database, so pulling all that information out and then tying it all together is a really big deal. It’s going to be really fun for people that are interested in that.

What’s been the strangest submission you guys have seen on the site?

Lewandowski: I don’t know if I want it in the article.

Kinloch: Aphex Twin’s sandpaper release? I don’t know if we let that in or not. There’s all kinds of weird things. I think somebody released something on a wax cylinder last year. We’ve also had to draw the line between what is a proper release that people can actually play, and what is a gimmick. That tends to lean towards art, where somebody gets a cassette, records something on it, and then smashes it to pieces with a hammer and puts it in a bag and sells it. We draw the line, I guess. You have to actually be able to listen to the thing.

Dahlstrom: Somebody [once] “played” a tree.

Kinloch: You guys know about the Egyptian vase thing that went on? The idea was when they were making these vases they would spin them round and they would get a reed and make a spiral on them. Somebody had the idea that there might be some sound that they recorded into that vase. I don’t think it worked, unfortunately.

David Garber is on Twitter, as well as Discogs.

This article was originally published on THUMP.

More

From VICE

-

(Photo by Sherry Rayn Barnett/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images) -

Photo by Guy Bell/Shutterstock -

Photo by Dezo Hoffman/Shutterstock -

Vinay Gupta: "People are too stupid to understand they're being handed a solution"