Editor’s Note: If you are struggling with a mental health issues in the US, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or contact the Suicide Prevention Resource Center . In Canada, visit suicideprevention.ca for more information on how to get help.

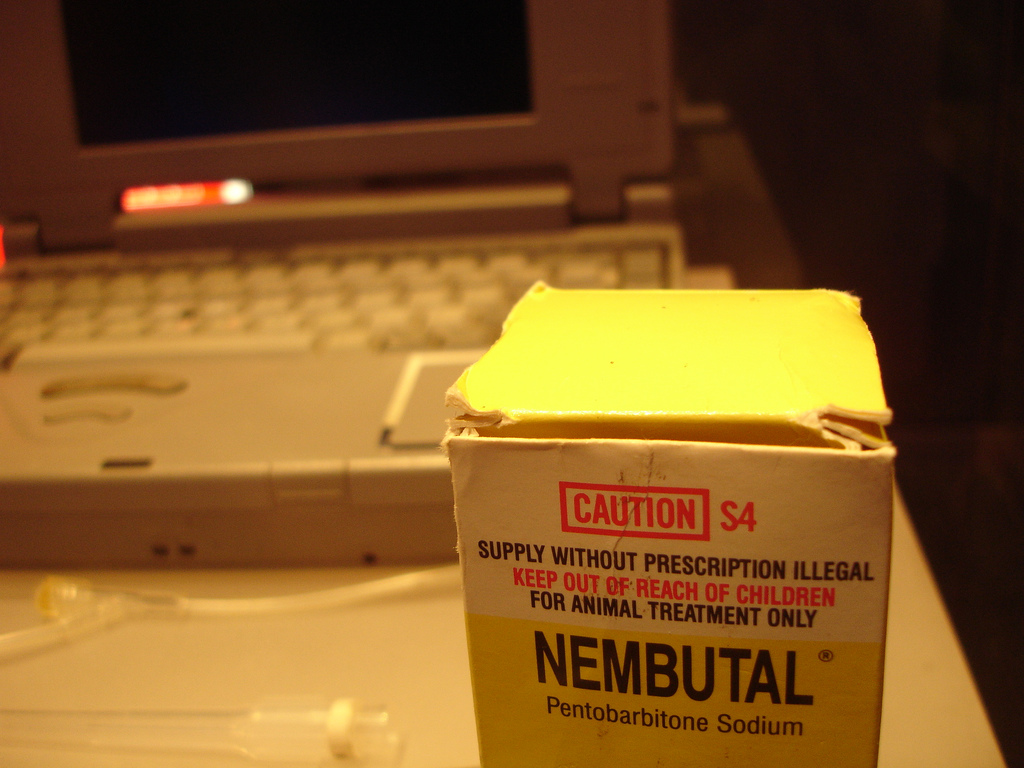

The first time Ruby and Jack used Bitcoin, it was to buy illegal drugs. Ruby, a retired adult educator, and her husband Jack, a retired paramedic, had both recently turned 60, but they weren’t looking for a chemical celebration. Instead, the Australian couple was trying to obtain pentobarbital sodium, better known as Nembutal, a fast-acting barbiturate that is lethal in low doses and a controlled substance in Australia, the US, and many Western European countries.

Videos by VICE

They thought that one day they might need the Nembutal to end their lives.

Although it can be used as a sedative and anticonvulsant by physicians, just 10 grams of Nembutal is enough to induce respiratory arrest and cause death in humans within a matter of minutes. The drug has been used at correctional facilities in the United States to execute prisoners and is regularly used by veterinarians, but it is perhaps best known as the substance of choice for right to die advocacy groups.

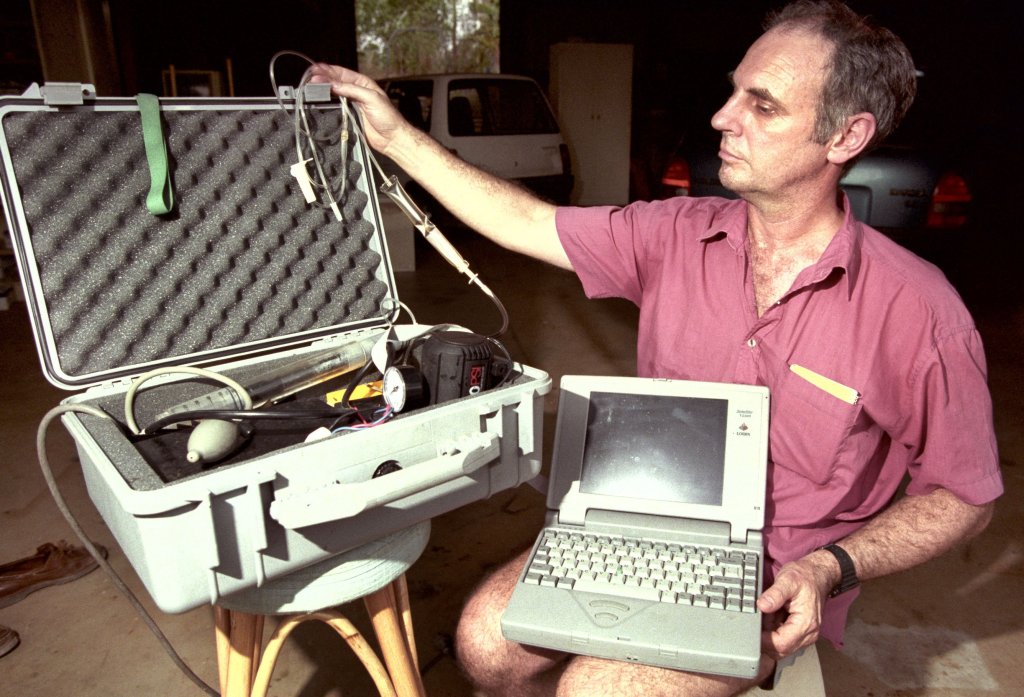

About four years ago, Ruby and Jack—whose names have been changed to protect their privacy and prevent attention from law enforcement—joined Exit International, an Australian right to die organization founded by the outspoken physician Philip Nitschke. In 1996, Nitschke had facilitated the first legal euthanization in history using a laptop running a software program he designed to administer a lethal dose of barbiturates with the click of a button. Shortly thereafter, however, Australia passed another law that prohibited physicians from euthanizing terminally ill patients. Nitschke created Exit International as an alternative to state-sanctioned euthanasia and physician-assisted death.

“Euthanasia” involves the physician ending a patient’s life, whereas “physician-assisted death” or “medical aid in dying” involves a doctor prescribing lethal drugs for a patient to end their own life. To date, five countries have legalized euthanasia: the Netherlands, Belgium, Canada, Colombia, and Luxembourg. Germany, Switzerland, one Australian state, and six American states allow physician-assisted death in a narrow range of cases. Right to die laws in these countries vary wildly, and even where it’s legal, it can be prohibitively difficult to convince the state that a terminally ill person is eligible for physician-assisted death and even more difficult to find a physician willing to participate in the program.

This restricted access to physician-assisted death or voluntary euthanasia leaves terminally ill patients with few options to end their pain. Those who can afford it can fly to countries like Switzerland, where the compassionate death organization Dignitas will assist them in dying, although this process can cost upwards of $10,000. Others choose to end their life in far less humane ways: the filmmaker Claude Jutra famously opted to jump from a bridge after being diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s, and patients in Canada have starved themselves in order to qualify for physician-assisted death. Most people, however, are left to live out their final days in agony, deprived of any avenues for a self-determined death.

Over the last three decades, the lack of options for terminally ill people looking to end their lives has led to the emergence of a tech-driven DIY euthanasia movement. DIY euthanasia is controversial among dignified death advocates, and easier access to lethal tools carries a significant risk of abuse. The activists in the so-called “deathing underground” consider self-determined exit to be a natural right and see technology as a potent avenue for deregulating death. These deathing activists believe their actions are a necessary alternative until laws change to allow terminally ill patients to legally and affordably end their lives on their own terms.

Australia, for its part, has debated the right to die for decades. The Northern Territory legalized euthanasia in 1996, but less than a year later, the law was repealed. Until recently, Australia denied all terminally ill patients the right to die. Last year, the state of Victoria voted to legalize assisted dying with a law that was called “the most conservative voluntary assisted dying model that has ever been proposed” by Victoria’s Premier. Shortly before Victoria passed its law, Ruby and Jack’s home state of New South Wales also considered legalizing assisted death. The legislation was defeated by a single vote.

All the while, Ruby was contending with her husband’s suicidal ideations, a result of Jack’s long battle with post-traumatic stress and crippling gut pain, the cause of which was never formally diagnosed. Yet even if the bill had passed in New South Wales, Jack’s mental health problems would have made him ineligible for the euthanasia program.

Ruby deals with pain, too. She has excruciating electric sensations in her face due to trigeminal neuralgia, a nerve disorder. But she said she doubts she would ever choose to end her life. Even so, after watching her father die and her 93-year-old mother—also a member of a euthanasia society—grapple with her own mortality, Ruby said having some Nembutal around gave her the peace of mind that if things ever get too bad, she has a dignified way to die.

“It’s difficult to contemplate or imagine why anyone would take their own life,” Ruby told me. “But being the partner of someone like that has really changed my view of suicide. When a person is ready to go, I think it’s more compassionate to let someone go out their own way than to try to keep them here.”

Image: Mads Bodker/Flickr

Nitschke agrees.

Following Australia’s ban on euthanasia in 1997, the then-50-year-old Nitschke created Exit International and found himself at the helm of a growing network of underground right to die activists who advocated non-physician assisted death as a workaround for restrictive laws governing a person’s ability to end their own life. These activists engaged in “deathing” by adapting household items for lethal ends and helping people use them. They also embraced the internet as a potent medium to spread knowledge about effective deathing methods and a way to connect terminally ill patients seeking to end their lives with activists who could help them make it happen.

Last October, Ruby and Jack consulted Exit International’s Peaceful Pill Handbook, a text that has been the subject of a number of censorship efforts in Australia since its publication in 2006, to learn how to order Nembutal on the internet.

“Jack really wanted to have something on the mantle to feel that he had an option for himself if he gets to a point of severe pain that he can’t manage,” Ruby said. “For the pair of us, ordering Nembutal was really just to know that it’s there.”

The e-book instructed them to download the Tor web browser and use ProtonMail, an anonymous email client, to contact a Nembutal supplier in Mexico. Neither Ruby nor Jack had ever used an encrypted messaging service before, and had only the faintest idea of what the “dark web” is and how it works.

Using information supplied by Exit International, Ruby and Jack established contact with the Nembutal supplier, who gave them a Bitcoin wallet address and instructed them to send $700 worth of the digital currency in exchange for the barbiturates. The only problem was the couple knew nothing about Bitcoin, and the Peaceful Pill Handbook lacked much information about how to go about acquiring or using it. After some research, Ruby and Jack decided to purchase some Bitcoin from CoinTree, an Australian cryptocurrency exchange.

“Ordering the Nembutal all happened very quickly,” Ruby said. “Getting the Bitcoin took the longest, actually. CoinTree had posted a notice saying that because of the popularity of Bitcoin now, a lot of transactions are happening and slowing down the whole process. It took a few days for the original transaction to get converted to something we could see in our account.”

Once Ruby and Jack had their Bitcoin, they sent payment to the Mexican Nembutal supplier who gave them a tracking number to trace their shipment. Once the shipment reached New South Wales, however, the tracking stopped. Australian customs officials had intercepted the package.

”Traditionally euthanasia workshops have just been about what drugs work and how to get them. Now we’re setting up courses on how to use Bitcoin and encryption.”

Stories like Ruby and Jack’s are familiar within right to die circles. Simply joining a right to die organization in countries where assisted death is illegal is enough to draw attention from law enforcement agencies. So for the last two decades, Nitschke and the right to die underground have explored technological solutions to deregulating death.

In many respects, DIY euthanasia is an outgrowth of the pervasive techno-libertarianism of Silicon Valley. Nitschke and the deathing counterculture see digital technologies as tools to subvert state control over life and death, a way to empower people who are actually suffering to make their own decisions.

Today, Nitschke leverages the ubiquity of the internet and sophisticated consumer technologies such as 3D printing, encrypted messaging, and cryptocurrencies to empower those seeking a self-determined exit. This DIY approach to assisted death and euthanasia is a source of much controversy, even among right to die advocates. As with any technology, there is always the risk of accidents and abuse. But for people like Ruby and Jack, the deathing underground is seen as the only option for a self-determined exit.

‘In 15 seconds you will be given a lethal injection…press ‘yes’ to proceed’

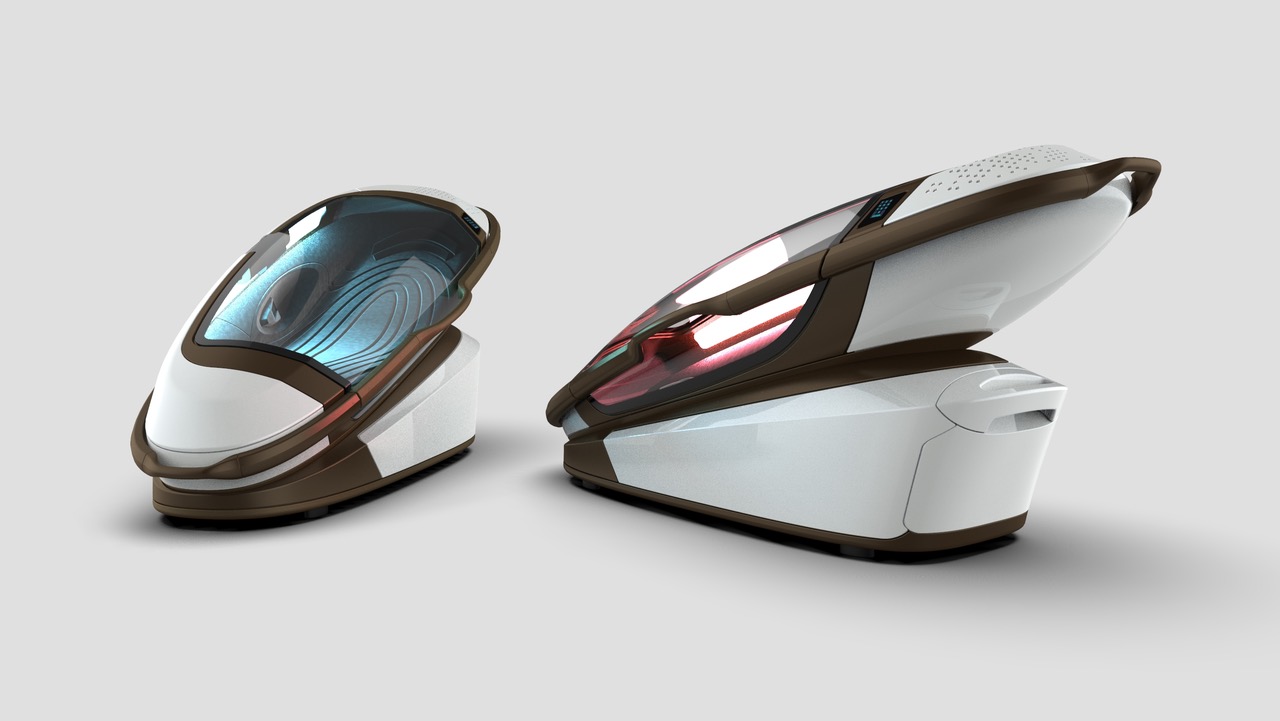

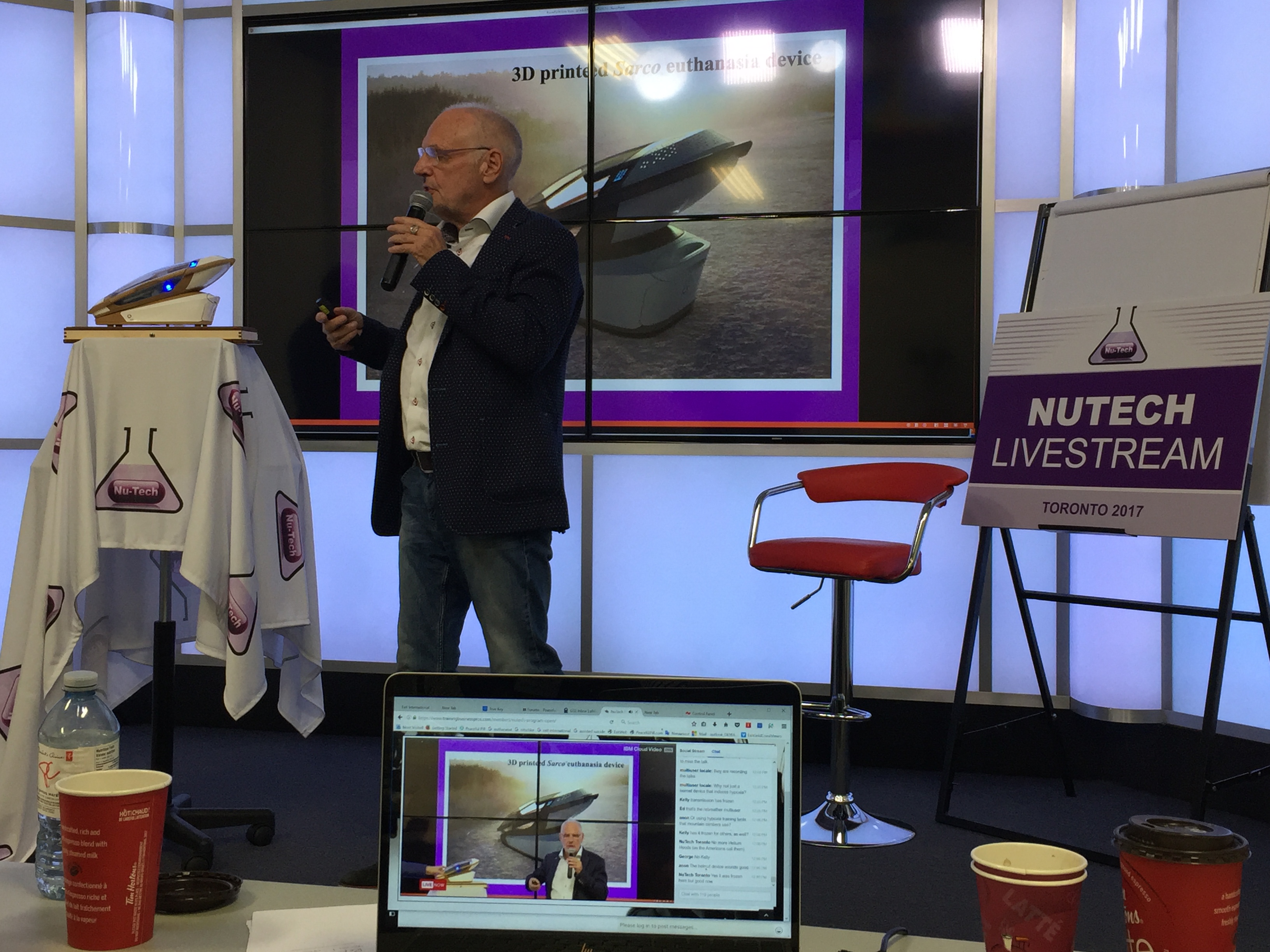

Last October, around the time Ruby and Jack were teaching themselves about Bitcoin, Nitschke gave a presentation in Toronto about Sarco, a device currently in prototype that will help people kill themselves. Billed by Exit International as the world’s “first 3D printed euthanasia machine,” Sarco is essentially a coffin connected to a supply of liquid nitrogen.

Before someone is able to use Sarco, they will have to complete an online psychiatric evaluation designed to ensure they are mentally capable of making the decision to end their life. If they pass the evaluation, they will be provided a code, valid for 24 hours, to unlock their Sarco machine. At any point within this time window, the user can climb into the capsule, close the hatch, and press the button.

At this point, oxygen will be evacuated from the chamber and replaced with nitrogen. According to Nitschke, the user will briefly experience euphoria before quickly losing consciousness. Within five minutes of pressing the button in the chamber, they will die.

Sarco is an open-source technology and the design will be made freely available on the internet once it’s completed. It’s a big machine, and Nitschke acknowledged that people would need access to an industrial-sized 3D printer to manufacture one. Its sleek, minimalist design makes it look very much like a gadget, which seems to carry the implicit promise that it is the future of DIY euthanasia.

Indeed, if Nitschke gets his way, Sarco will be the opening salvo in a technological revolution for modernized self-deliverance.

Understandably, Nitschke’s so-called “suicide machine” generated a lot of press, seemingly none of which contextualized the device in the larger conversation about death, technology, and self-determination. Sarco is doubtlessly a sensational machine, but digital technologies have occupied a central role in the deathing counterculture for decades.

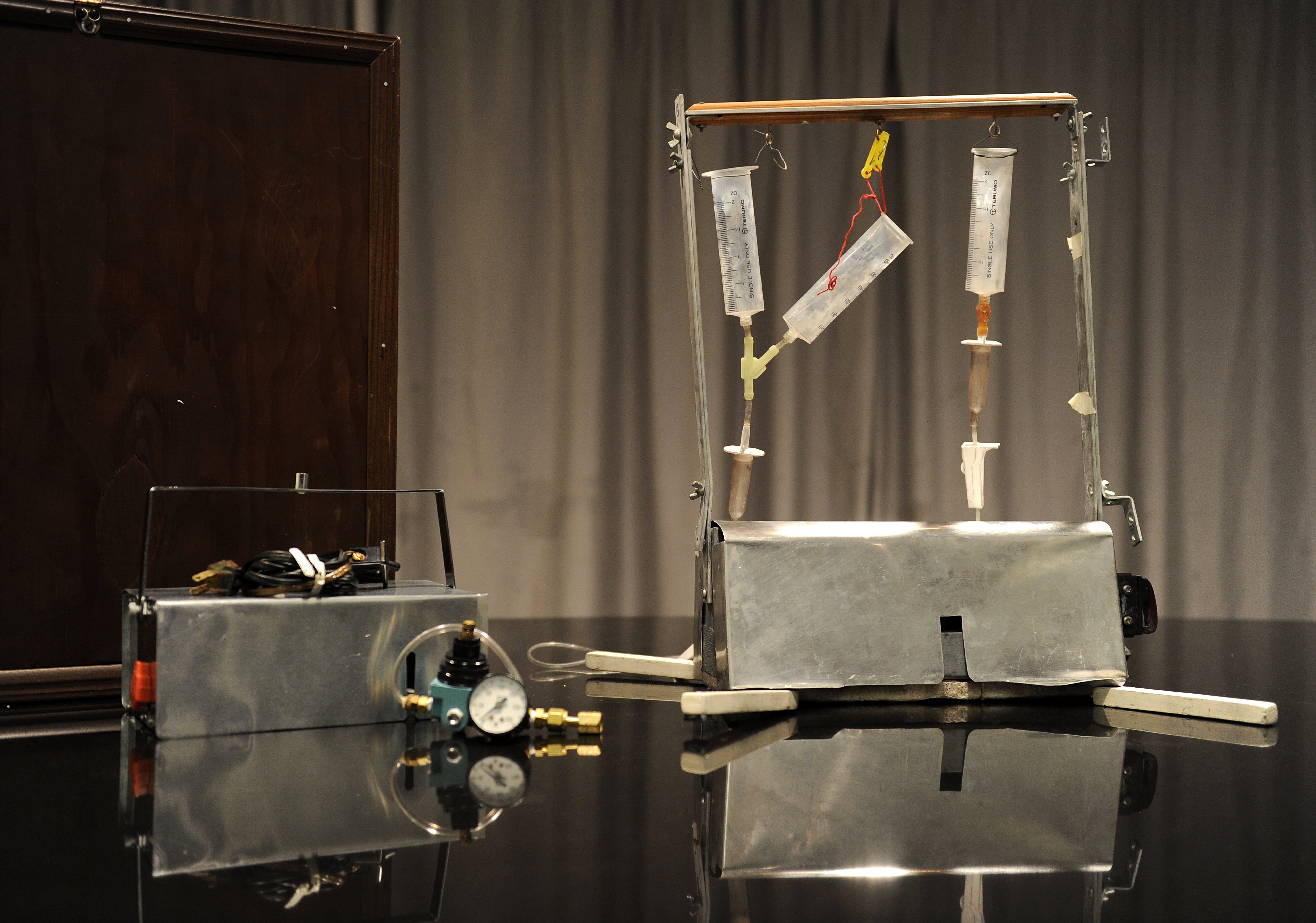

The issue of non-physician assisted death first entered public consciousness in a big way in 1990, when Jack Kevorkian, a physician better known by his media moniker “Dr. Death,” euthanized Janet Adkins, 54-year-old Michigan woman with Alzheimer’s disease, from the back of his van. It was the first in a series of “mercy killings” facilitated by Kevorkian that would eventually result in an eight-year prison sentence.

In the case of Adkins, Kevorkian used a device he called the Thanatron, a crude assemblage of three IVs: one to inject saline, one to inject a barbiturate, and a third to administer a lethal dose of potassium chloride. The patient could progress from one IV to the next by pressing a button. After facilitating two assisted deaths using the Thanatron, Kevorkian developed a new machine called the Mercitron that delivered a patient a fatal dose of carbon monoxide. With both of these machines, however, it was the patient who ultimately pushed the button that would end their life.

George Annas, Director of the Center for Health Law, Ethics & Human Rights at Boston University, argued in a 1991 article published in a Hastings Center report, media fascination with Kevorkian had less to do with the doctor himself than his machines.

“Machines have a tendency to depersonalize death and to make us seem less responsible for it,” wrote Annas, who argued if Kevorkian had pointed a gun at Adkins’s head or simply given her a rope to hang herself, the question of whether or not his actions were murder or manslaughter would be much more clearcut. Likewise, if Kevorkian had just given Adkins some pills, “it is unlikely he would have been charged with anything.”

“But [Kevorkian] took an intermediate position: devising his own machine which has no medical use,” Annas added, “but because of the IV and drugs involved, seems to be a medical machine. The ‘suicide machine’ stands as a hybrid between medical and nonmedical technology.”

Across the Pacific Ocean, Nitschke followed the Kevorkian trial with a detached interest. For most of his career as a physician, Nitschke hadn’t thought much about euthanasia. But when the proposed Rights of the Terminally Ill Act was challenged by the Australian Medical Association in 1995, Nitschke, along with “very few” other physicians, signed a letter in the Northern Territory advocating for the patient’s right to determine their own death. Almost overnight, Nitschke became the unofficial spokesperson of Australia’s right to die movement.

Shortly after the passage of the Rights of the Terminally Ill Act in 1996, Nitschke made history by becoming the first person in the world to legally euthanize a human. Robert Dent, Nitschke’s first patient, was described by The New York Times as a man in his 60s in pain from advanced prostate cancer. Aside from being the first such euthanization in history, the patient’s death was notable for another reason—it was facilitated by a laptop computer.

The computer, a Toshiba laptop that Nitsckhe would also use to surf the internet and answer email, was running a simple software program developed by Nitschke called ‘Deliverance,’ which would ask a patient three questions. The first two ensured that the patients understood that they were about to kill themselves: “Are you aware that if you go ahead to the last screen and press the ‘yes’ button you will be given a lethal dose of medications and die? Are you certain you understand that if you proceed and press the ‘yes’ button on the next screen you will die?”

The final question was blunt and to the point: “In 15 seconds you will be given a lethal injection…press ‘yes’ to proceed.”

If the user clicked “yes,” it would trigger the computer to release a lethal dose of barbiturates through an intravenous needle in the patient’s arm after the 15-second delay. Shortly thereafter, the black and white computer screen would go blank, except for a single word: “Exit.” The patient would quickly lose consciousness and die within a matter of minutes.

“I watched what Kevorkian was doing in the US and thought I could improve on it a bit,” Nitschke told me. “His machines looked kind of amateurish, but it was very impressive that he made them so that the patient was in control.”

To be sure, Nitschke’s Deliverance machine was an improvement over Kevorkian’s relatively crude Thanatron and Mercitron devices. Still, Nitschke was dissatisfied with the way the computer mediated the euthanasia process. In his opinion, it hadn’t gone far enough.

Subtleties in Australia’s euthanasia law meant that a doctor couldn’t actually administer the drugs that would result in someone’s death—patients had to do that themselves. In this respect, Nitschke’s Deliverance software was a significant improvement in that he didn’t have to be in the room “taking up space,” as he put it, around the grieving families. Still, merely accessing the machine required patients to undergo a rigorous psychiatric evaluation by state-sanctioned physicians. Nitschke claims neither the psychiatrists nor terminally ill patients were prepared for this sort of ordeal.

“Even back in 1996 my patients dreaded their visit to the psychiatrist,” Nitschke said. “The psychiatrist would say ‘Oh no, you sound depressed.’ Well of course they’re all depressed—they’re going to die.”

“It’s not a question of if you’re depressed,” Nitschke added, “but if you’re so depressed that you’ve lost your ability to know what you’re doing.”

In the future, Nitschke hopes euthanasia devices like Sarco will incorporate artificial intelligence that will be able to determine whether a person has the mental capacity to make the decision to end their life, so as to avoid the painful ordeal of visiting a psychiatrist for approval. Although this technology wasn’t available when Nitschke developed the Deliverance machine, four of his terminally ill patients used the machine to die before the law that legalized assisted death in the Northern Territory was overturned in 1997.

Australia’s abrupt about-face on legal euthanasia in 1997 meant that Nitschke could no longer help patients die with his Deliverance machine—but it didn’t mean he couldn’t empower terminally ill patients to die in a peaceful manner.

CTRL + DEATH

That same year, Nitschke founded the Voluntary Euthanasia Research Foundation, a right to die organization that would eventually become Exit International. The purpose of the organization was to provide information to terminally ill patients who were considering ending their life. This included everything from practical information about how to find lethal drugs and their requisite dosages to how to discuss such a sensitive issue with loved ones.

In 1998, Nitschke expanded the scope of Exit International by launching NuTech, with the express purpose of developing new technologies to assist the terminally ill in DIY euthanasia. In June of 1999, Exit International hosted its first NuTech conference in Berkeley, an invite-only affair that attracted prominent right to die activists, including Derek Humphry, who had recently authored a best selling book on DIY euthanasia.

The success of that inaugural NuTech conference prompted Nitschke to host another gathering in Seattle the following November. The two-day event was closed to the public with two notable exceptions: a pre-selected pair of journalists was allowed to witness tech demos and a doctoral student named Russel Ogden was allowed to attend the entire event as an outside observer.

Having made a name for himself in academia as the world’s only expert on underground euthanasia (a distinction he arguably still holds to this day), Ogden is perhaps the only non-activist to attend an entire NuTech conference. In 1994, Ogden published his thesis on non-physician assisted death among AIDS patients while pursuing a Masters at Simon Fraser University, and immediately found himself embroiled in controversy. Shortly after publication, Ogden was summoned to a Coroner’s Court and ordered to turn over information about one of the anonymous subjects in his thesis, someone who the court believed was related to a death it was investigating.

Ogden refused to appear in court on the grounds it would violate the terms of confidentiality with his subjects. He would go on to win a landmark Canadian case, but in the process was legally abandoned by Simon Fraser University. Ogden then sought to pursue his PhD at the University of Exeter in UK, which had promised to support his research on underground assisted death. Exeter’s ethics committee eventually backtracked on this commitment and Ogden left the program in 1998, after the university said it wouldn’t support total anonymity for the 100 subjects he had interviewed who had helped terminally ill AIDS patients to die. The results of this unprecedented study remain unpublished.

Despite his professional hardships, Ogden’s commitment to studying non-physician assisted death earned him a spot as an observer at the second NuTech conference in 1998.

The event was generally closed to the public because its attendees all practiced DIY euthanasia and wanted a space to discuss their practices openly and confidentially. (Today, the event is a bit more open—some discussions at last year’s NuTech gathering were live streamed.) As detailed by prominent right to die activist John Hofsess in his own farewell letter, underground assisted deaths often felt like a criminal activity (and in the eyes of the law, being involved with assisted deaths often is illegal), despite the best intentions and consent of everyone involved. Hofsess detailed how activists would work with their patients to ensure that their deaths looked natural, which involved placing false evidence, such as sending spouses out to get time-stamped receipts from stores. At the same time, Hofsess and his partners would don gloves and booties to ensure that they left no trace of their presence at the scene of the ‘crime.’

Ogden’s report on the second NuTech conference was published in Death Studies shortly after the event and describes a small affair consisting of a dozen right to die activists from around the world who were united in their recognition of a “technological imperative” when it comes to non-physician assisted death.

“With internet-enhanced capacity to share ideas, technology is facilitating the goals of the global right to die social movement,” Ogden wrote. “For a small but influential segment of the right to die movement, a ‘technological imperative’ has arrived—that is, the drive to make full use of equipment to hasten death.”

According to Ogden’s report, the main technologies discussed at the NuTech conference were velcro-sealed plastic bags known as exit bags that patients could place over their head to cut off the flow of oxygen to the brain, and a device called the Debreather, a modified scuba system that gradually replaces a patient’s oxygen with nitrogen until they lose consciousness and die. The attendees discussed their experiences using these devices in detail, noting difficulties they had had with patients or unforeseen technical troubles. At one point during the conference, Ogden recounts, an attendee demonstrated the debreather, lowering his oxygen intake levels down to 8 percent (had they reached about 5 percent, they would have lost consciousness).

Unsurprisingly, the nascent DIY euthanasia movement described by Ogden was met with concern not just from the general public, but also from other right to die advocates.

The psychologist James Werth took to the pages of Death Studies shortly after Ogden’s report from the conference was published to express his views. Although Werth sympathized with the aim of the movement to “put the power of controlling the time and manner of death in the hands of lay advocates and people who are suffering,” Werth was concerned that it would lead to still more stringent anti-euthanasia laws.

Werth was also concerned with the idea of lay persons using deadly technology without proper experience.

“My fears are not related so much to deliberate abuse, at least not at the start of such a movement, as they are to lack of knowledge among assisters and resulting premature deaths,” wrote Werth, who declined to be interviewed for this article. Still, Werth noted that “the development of alternatives to physician assistance using controlled substances has progressed too far at this point to be aborted or thwarted.”

Indeed, a disturbing report by Ogden from the early 90s found that many first-time non-physician assisted death attempts were botched, often in gruesome ways. In the report—in which Ogden interviewed 17 individuals, including nurses, doctors, and two priests who had helped people with AIDS end their life—he found that in one instance of a botched assisted death the assistant had to shoot their patient. Another case ended with the deathing practitioner slitting their patient’s wrists to induce death. Two other cases ended with the administration of heroin. Still, Ogden argued in a response to Werth that there is not enough empirical evidence to decide whether the benefits of DIY euthanasia outweigh its harms.

“Before the alarmists lead a moral panic, it bears mention that any dangerous implications for NuTech depend on who controls the devices, the conditions of the control, and the ends that they serve,” Ogden wrote. “Our current state of knowledge means that only empirical investigation can help us resolve the issues and concerns that Werth and I raise.”

The empirical data to decide one way or the other is still lacking and Ogden, who was perhaps the only academic researcher in the world investigating underground euthanasia, has stopped pursuing the subject. In 2008, he signed an agreement with Kwantlen Polytechnic University in British Columbia that barred him from researching, teaching, or discussing the topic of assisted death. He declined to comment for this article.

BITCOIN AND BARBITURATES

In retrospect, many of the fears and hopes that coalesced around the NuTech movement turned out to be largely unfounded. Twenty years after launching the organization, Nitschke said NuTech never took off like he hoped.

“It’s been spectacularly unsuccessful, it’s almost embarrassing,” Nitschke told me. He attributes the lack of success in this area to the social stigma that surrounds assisted death in most countries, which deters people from collaborating with him on developing new euthanasia technology.

“I’m rather disappointed that we haven’t seen more innovative ideas coming forward,” Nitschke added. “I’m hoping that’s soon going to change.”

Despite a lackluster response to his call for DIY euthanasia technologies, Nitschke hasn’t stopped developing projects on his own, mostly by repurposing everyday devices for deadly ends.

In 2002, Nitschke created the COGen machine, which consisted of a canister to mix chemicals that would produce carbon dioxide that could be inhaled by attaching a facemask to the canister. That same year, Nitschke also began producing plastic “exit bags” modeled after the ones demoed at the second NuTech conference that sold for $30 apiece.

In 2008, Nitschke released the details for a new euthanasia machine that repurposed propane tanks normally reserved for barbeques, filled them with nitrogen, and then attached the tank to a plastic tube. This tube was routed into a sealable plastic bag that a person could place over their head to administer a fatal dose of nitrogen. As Nitschke soon discovered, acquiring nitrogen canisters could be difficult. To this end, he started a beer company, Max Dog Brewing, so that he could legally import and sell nitrogen canisters to be repurposed for euthanasia if a customer so chose.

“The ‘suicide machine’ stands as a hybrid between medical and nonmedical technology.”

That same year, Nitschke released the online version of The Peaceful Pill Handbook. Stopping just short of being a suicide how-to manual, the book details over 15 methods of euthanasia ranked according to reliability and peacefulness. The book was temporarily banned in New Zealand and subject to internet censorship in Australia, where it remains controversial. In 2016, Australian customs officers seized and destroyed copies of the book that were brought into the country, where using any electronic methods to spread information about assisted death is still punishable with a $110,000 fine. Authorities have yet to charge anyone for downloading Nitschke’s book.

According to Nitschke, making the Peaceful Pill Handbook an online-only affair has been both a help and a hinderance. On one hand, elderly people must be comfortable using the internet to access the book, but digital publication also makes the text available to a global audience and allows Exit International to push out developments as they happen—Nitschke said he updated the book nine times in 2017 alone, and these updates were delivered by email to anyone who had a digital copy of the book.

Of course, making DIY euthanasia information easily accessible online has its risks. In 2014, a 26-year-old Australian named Lucas Taylor killed himself, allegedly after soliciting advice from an online forum run by Exit International. Taylor had lied about his age to gain access to the forum, but his death was used by his family as an example of why groups like Exit International should be banned from posting information about deathing techniques on the internet.

Nitschke, a staunch free speech advocate, said he is quite used to these sorts of attacks. In an attempt to prevent copies Peaceful Pill Handbook from falling into the wrong hands, Nitschke said it’s now subject to a “pain in the ass” vetting process that requires people to prove their age before receiving a copy. As with any digital artefact, however, once the book is published online it is difficult to control and limit access to the text due to peer-to-peer sharing networks and other modes of unofficial transmission.

“Families understandably get upset and then lash out, wanting to know why their child was able to get this information,” Nitschke said. “A young person dying is not good, but it has to be balanced with the fact that thousands of elderly people get the very same information and benefit from it.”

Despite his various tech-oriented approaches to DIY euthanasia, Nitschke still says the use of drugs like Nembutal is the most reliable and peaceful method.

Nembutal is a controlled substance or only available by prescription in the US, Australia, and many Western European countries, which means that most people who want access to the drug have to order it online from countries like China or Mexico. Aside from being illegal, this method of obtaining Nembutal makes it difficult to determine the quality of the chemical— and when someone is using it to end their life, they want to be certain it will work. In 2009, Nitschke released a barbiturate testing kit that would allow anyone to determine the concentration of the lethal chemical in their supply.

The testing kit was an important aspect of Nitschke’s euthanasia efforts, but nothing compared to a seemingly unrelated event that occurred the year before—the publication of Satoshi Nakamoto’s paper describing a cryptocurrency called Bitcoin.

Nitschke didn’t realize it at the time, but Bitcoin would end up becoming a major facet of his right to die advocacy. According to Nitschke, the rise of dark web drug marketplaces like the Silk Road in 2011 was a major boon to people looking to safely buy reliable barbiturates for euthanasia. The downside is that purchasing these substances from dark web markets requires knowing how to buy Bitcoin and use encrypted chat services, which has proven to have a steep learning curve for elderly patients.

For a few years, dark web marketplaces flourished and provided a reliable source of lethal drugs for people looking to euthanize themselves. More recently, however, most major dark web marketplaces have been shut down by law enforcement, forcing these terminally ill patients to look elsewhere for their drugs.

But even though the dark web marketplaces are mostly gone, Nitschke tells me many of the websites that traffic in Nembutal still require payment in Bitcoin. This, he said, has led to a large increase in people reaching out to Exit International for advice on how to use encrypted messaging services and Bitcoin. To meet this demand, Exit International is designing workshops to teach people how to communicate securely online and use cryptocurrencies to buy their chemicals.

”Traditionally euthanasia workshops have just been about what drugs work and how to get them,” Nitschke said. “Now we’re setting up courses on how to use Bitcoin and encryption.”

THE FUTURE OF DIY EUTHANASIA

Most Americans support voluntary euthanasia, according to a Gallup poll from 2017. But many physicians, psychologists, and lawmakers reject Nitschke’s DIY approach. There are plenty of anti-euthanasia groups that reject the practice outright on religious grounds, but others resist voluntary euthanasia and assisted death based on the concept of what it means for a doctor to alleviate suffering.

Writing in The Conversation, University of Monash professor of medicine Paul Komesaroff argued that Nitschke’s calls for the legalization of euthanasia and his promotion of non-physician-assisted death solutions are misguided and counterproductive. Instead, Komesaroff advocates for codifying the “double effect” principle when it comes to end-of-life care.

The double effect principle obliges a doctor to administer drugs—which may be barbiturates—to ease a patient’s pain. If this patient has expressed a desire to die, these pain-relievers can be administered in such a way over time so that in addition to relieving pain, they have the “double effect” of killing the patient. Unlike euthanasia, it doesn’t violate a physician’s ethical imperative to do no harm and it’s an end of life option available to anybody. Other opponents of physician-assisted death and voluntary euthanasia argue that the practices would be totally unnecessary if governments instead focused on providing better palliative care options.

DIY death is a part of the right to die movement that many doctors and patients’ rights groups fighting for more progressive laws don’t want to talk about. I attempted to speak with about a dozen death with dignity groups and physicians who have spoken or written on the issue. The few that responded declined to comment. The rest left my emails unanswered.

Most deathing activists admit that their DIY solutions are just workarounds for laws prohibiting voluntary euthanasia and physician assisted death. Nitschke argues that if governments took a more enlightened position on the right to die—he points to the Netherlands as an example of particularly progressive euthanasia policy—many of these DIY solutions would be superfluous. But for now, it doesn’t look like any major legal changes will end the widespread prohibition on physician assisted death and voluntary euthanasia.

In fact, Nitschke argues that the crackdown on the right to die movement has intensified in recent years.

In 2009, Nitschke and his wife were detained at Heathrow Airport in London for nine hours and were questioned about the right to die conference they were attending. In 2014, the euthanasia advocate Max Bromson used Nembutal to end his life in a hospital room surrounded by family members. After his death, Exit International’s office in Adelaide, Australia was raided by police who seized Nitschke’s phone and computers. No charges were ever brought against Nitschke.

In April 2016, British police forced their way into the home of Avril Henry, an 81-year-old retired professor in failing health. Henry was a member of Exit International and after police smashed through the glass door of her home at 10 PM, officers questioned her for six hours and confiscated her bottle of Nembutal. Worried that the police might come back and find her remaining stash of the substance, Henry used it to take her life four days later.

Later that year, New Zealand police set up a roadblock outside an Exit International meeting as part of Operation Painter. During this sting operation, all the attendees at the conference had their names and addresses recorded by the police. Later, some of the elderly attendees had police search their homes without warrants, and many electronic items like computers and tablets were seized, in addition to personal letters.

When Ruby and Jack’s Nembutal was intercepted last year, they didn’t hear anything from the government for two weeks. Then one afternoon, Ruby said a pair of local police officers showed up unannounced at their home. Ostensibly, the officers came to check on Jack’s wellbeing, but when Jack asked if they had actually come to inquire about the Nembutal, Ruby said the officers grew visibly uncomfortable.

While she wasn’t able to confirm that this was in fact the real reason for the visit, Jack, having previously worked as a health professional himself, believes that the police had come with the paperwork necessary to commit him to a mental institution if judged a danger to himself or others. Moreover, if the Australian authorities decided to prosecute them for importing Nembutal, Ruby and Jack could’ve been hit with $800,000 in fines and/or imprisonment.

Ruby said she and her husband may end up trying to order Nembutal again, though they worry that their names and addresses are now “marked” by customs officials. She said that not having access to the Nembutal has been a point of stress for Jack, who has few other options. He could, of course, overdose on the pain pills he takes on a daily basis, but this is not guaranteed to work and could possibly leave him in a vegetative state, a burden he wouldn’t want to leave for Ruby.

For Nitschke, things came to a head in Australia in 2014 after he was approached by Nigel Brayley, an attendee at one of Nitschke’s seminars who was under investigation for murder, something that Nitschke has said he was not aware of at the time. Brayley had already obtained Nembutal and later used it to kill himself rather than face a life in prison. Afterward Nitschke had his medical license revoked by the Medical Board of Australia for aiding Brayley’s suicide.

“I wish I had never met Nigel Brayley, frankly, given the amount of damage that brief encounter has done to me and the time and energy and money that it’s consumed,” Nitschke told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation during the trial. Still, Nitschke saw a silver lining to the experience.

“Even though I say I wish I’d never met Brayley, I am pleased about the fact that it enabled us to talk for the first time in a very much broader domain about the issue of rational suicide,” he said. “It won’t change my advocacy.”

The Medical Board of Australia’s decision was reversed in 2015 and Nitschke had his license reinstated after an Australian court found the license revocation to be unlawful. But he said he had had enough of Australia. He burned his medical license and moved to the Netherlands.

“In the Netherlands, the argument is about whether or not a person over a certain age should just be given the euthanasia drugs if they want them,” Nitschke said. “They don’t have to give a reason, they’re just eligible. That’s what we want to see: a rights model, rather than a medicalized model where physicians have to sign off.”

Still, Nitschke told me that even in the Netherlands—where approximately 4.5 percent of citizens voluntarily end their lives with euthanasia, far more than any other country—people are wary of associating with him based on his views about the right to die.

The artist who had been collaborating with Nitschke on the Sarco machine abruptly ended his contributions after being awarded a high profile artist residency, out of fear that his association with Nitschke’s project would damage his reputation. Likewise, a company that was providing the liquid nitrogen for Nitschke’s prototype Sarco machine ended its contract after learning what the device would be used for.

Read More: Canada is Legalizing Assisted Suicide, But That Doesn’t Mean Doctors Will Do It

Nitschke said the struggle is worth it. He hopes that after two decades of technological stagnancy with regard to euthanasia, the Sarco machine will spur a DIY tech revolution in the right to die movement. According to Exit International, last year’s NuTech conference in Toronto was a success and drew 200 international viewers to its live stream as well as a number of notable speakers in the right to die community, including the inventor of a proposed euthanasia roller coaster.

“As the baby boomers are getting to their twilight years, they’re less inclined toward this ‘see if the doctor approves’ euthanasia strategy,” Nitschke told me. “A lot of people say they like the idea of having a doctor present, but when you dig down a bit, what they really don’t want is failure. They don’t want something that might end their life, they want something that will end their life. This leads back to DIY.”

Nitschke related to me the first time his Deliverance machine was used to euthanize one of his patients, in 1996. Rather than it being a cold experience where death was mediated by a machine, Nitschke said it was “humanizing.” The patient quickly navigated the “Do you want to die?” questions on his own before pushing the machine to the side and holding his wife as the barbiturates began to circulate through his body. Within minutes he had passed away—or in the parlance of the euthanasia underground, he was “delivered.”

“Death is not a medical process, it’s a natural process,” said Nitschke. “I see the issues around euthanasia as purely technical. They can be overcome with better technology.”