You might have to experience the end of the world sober, after all.

That’s because climate change will unleash havoc on the world of drugs. And it may be a whole lot tougher on the most mainstream stimulants—grocery store stuff like coffee, beer, and wine—than on hardcore illicit narcotics like heroin, cocaine, and meth.

Videos by VICE

Some of those more-powerful, more-addictive, mind-altering substances appear relatively better prepared to survive the oncoming climate crisis than the vulnerable plants responsible for producing traditionally legal recreational highs, according to a review of recent scientific studies and interviews with experts on climate and agriculture by VICE News.

Heroin, for example, is already getting a boost from climate change. One study shows that rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide have doubled the potency of poppies, the plant used to make the drug. Wine, by contrast, is under serious threat, as changing weather patterns and raging wildfires put celebrated vineyards in jeopardy.

“All plant-based drugs, whether they’re narcotics or used for medicine, are going to change,” Lewis Ziska, lead author of the poppy study and now an associate professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, told VICE News. “In fact, the world is changing faster than our ability to describe the changes.”

Though big questions remain about how climate change will impact agriculture, and experts caution that much research remains to be done, long-term agricultural consequences are just starting to come into view.

The short version: The drug world is facing a big shake-up.

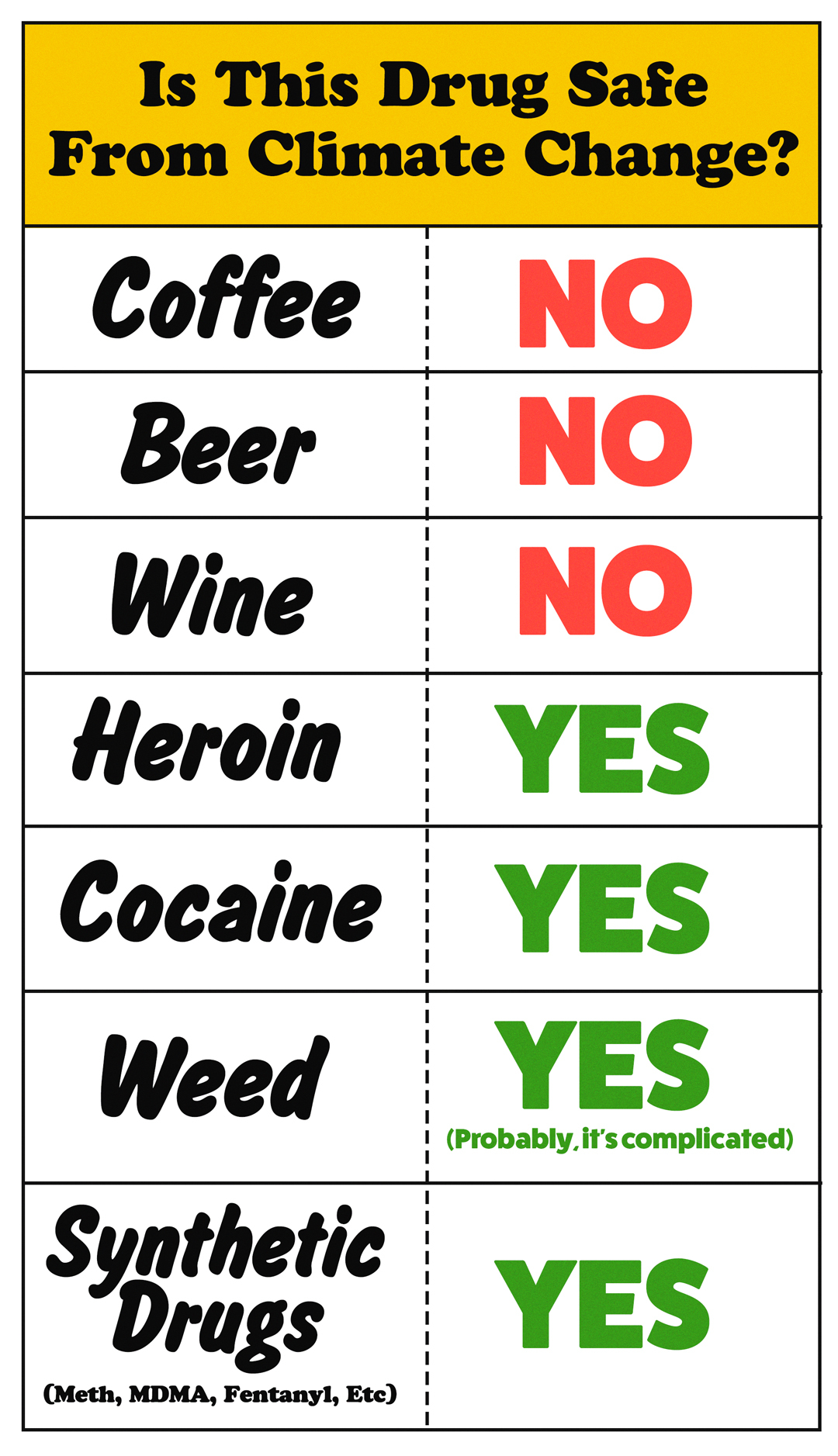

To make this easier, we put the results into an oversimplified but handy-dandy chart.

For a more detailed picture, read on.

BEER: DOUBLE THE PRICE

Get ready to pay more for brew.

Climate change might make beer twice as expensive, according to a 2018 study. In Ireland, one of the heaviest beer-drinking countries in the world, the price could triple.

That’s because the cost of a key ingredient, malted barley, could soar as global average temperatures rise and barley becomes harder to grow.

The price of a six-pack in the United States might rise by as much as $8 on average, the study found.

Pricey beer is just “another way climate change will suck,” tweeted Steven J. Davis, one of the authors of the study.

WINE: A HINT OF ASHTRAY

Wine is decidedly in trouble.

At least, the good stuff is: Those who savor the fine distinctions between a pinot noir and a cabernet sauvignon, or a Bordeaux and a Chateauneuf-du-pape, are going to hate the future.

The world may still be able to produce the same amount of wine as before. But the quality, taste and variety of wines will change, said Benjamin Cook, a NASA climate scientist who has studied the impact of climate change on wine-growing regions.

“You can grow wine grapes almost anywhere and make wine with them. That’s why you can go to Trader Joe’s and get 4-buck chuck,” Cook told VICE News. “Wine that has these characteristics that make it famous and expensive and high value, that’s where the impacts are going to potentially be very severe.”

Those nuances depend on the regional mix of weather, rainfall, temperature and humidity—all of which will be thrown into chaos. Warmer wine-growing regions, like Australia and California, will be particularly hard hit, Cook said.

California vineyards are especially threatened by the recent surge of climate change-linked wildfires. Grapes that escape the flames can absorb chemicals from smoke that ruin their taste, leaving the dreaded “smoke taint.” Some winemakers complain that smoke exposure is giving their wine an “ashy finish,” according to The Washington Post.

Others are reaching for solutions. Kwaw Amos, owner of New York’s Gotham Winery, blends traditional European grapes with hardier American varieties to create hybrids with better protection against heat, fungus and early budding.

“The concept of hybrids is nothing new in grape growing,” Amos told VICE News. “Cabernet sauvignon is a hybrid. It’s just now you’re thinking about the next level hybrids that we’re going to need given what’s happening.”

COFFEE: DARK TIMES

Coffee is in danger.

About half of all land now used to grow the two main species of coffee, arabica and robusta, may no longer be usable by 2050, according to one estimate. Arabica and robusta make up 99 percent of the commercial supply globally, and have a limited ability to relocate to different climates.

Another study found that six-in-ten of the known species of coffee are now under threat of extinction. Experts believe higher temperatures encourage pesky fungus growth on coffee beans. Changes in rainfall patterns may also put an added stress on the plants.

Good coffee will probably become increasingly harder to grow. And that could become a global economic issue, considering the industry employs over 125 million people, including farmers, distributors and brewers. And, like beer, coffee could also get more expensive.

“U.S. consumers should expect much more expensive and lower-quality coffee because of rising temperatures, extreme rainfalls, and higher frequency of severe droughts,” Titus O. Awokuse, who chairs the department of agricultural, food and resource economics at Michigan State University, recently told the LA Times.

COCAINE: FINE, THANKS

Coca, the plant responsible for cocaine, is notoriously difficult to get rid of. And that likely means it will survive pretty well compared to more-vulnerable plants.

Charles Helling, a scientist who studied the crop as a soil chemist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, has said he thinks higher temperatures won’t be harmful, and that they may just encourage the plant to grow at even higher elevations.

“Coca is kind of unique, because it’s got a very heavy wax cuticle, a layer on the leaves,” Helling told Scientific American. “So that tends to protect it from water loss. It’s a pretty hardy shrub. It’s actually a lot hardier than a typical crop plant.”

Another factor in coca’s favor may be genetic diversity. Plants that have been extensively cultivated in mainstream agriculture tend to become more genetically homogeneous, Ziska said. Whereas plants that have thrived in the wild—not to mention, survived sustained attempts at eradication—may demonstrate greater genetic variability that helps them respond more flexibly to a changing environment.

It’s still unclear whether coca would benefit from such an advantage.

HEROIN: AS YOU LIKE IT

Poppy plants, as noted above, have already become twice as potent in natural morphine as they were in the middle of last century, thanks to rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide, or C02, the gas that’s principally responsible for climate change, according to one study.

That study was performed in 2008, and atmospheric C02 has only continued to rise since. Pumping even more of that gas into the air may triple morphine levels by 2050, and increase potency by a factor of 4.5 by the year 2090, according to the same study.

Ziska said the reason isn’t yet completely certain. But he said one theory suggests that when a given resource becomes more prevalent in an environment, plants will tend to produce more It’s particularly drought-resistant.

The poppy’s hardiness has enabled growers in Afghanistan, a narcostate which provides 90% of the world’s opium, to notch record harvests over the last decade.

CANNABIS: IT’S COMPLICATED

Weed will probably be okay—mostly.

The plant is likely well-suited to survive a moderately hotter and drier climate, according to Olufemi Ajayi, the author of a recent study on the relative dangers posed by insect pests to cannabis in the context of climate change.

But, he cautioned, only within limits. More extreme temperatures and droughts will stunt growth, or kill plants, he said.

Another 2011 study on the impact of higher concentrations of carbon-dioxide found that the plant may be able “to survive under expected harsh greenhouse effects including elevated CO2 concentration and drought conditions.”

Cannabis does have an otherwise unsavory link to environmental degradation, however (as do a lot of drugs: see our previous reporting here).

Indoor growing operations have spread rapidly along with broadening legalization, and they take a lot of electricity.

One estimate states that growing one ounce of cannabis indoors can emit as much greenhouse gas as burning through a large car’s entire tank of gasoline—or 7 to 16 gallons.

Most U.S. cannabis is grown indoors. As the industry expands, its energy consumption is expected to rise, too. In Colorado, emissions from cannabis farms already exceed those from the state’s coal mining industry.

In other words, weed’s relationship to global warming is complex. Even if cannabis is well-positioned to withstand a moderately warmer climate, its own energy use and outsized carbon footprint will need to be accounted for if the world ever gets serious about reducing emissions.

SYNTHETIC DRUGS: FINE

The world of synthetic, lab-based drugs will likely see hardly any impact from climate change, experts including Ziska said. This is because they’re made in a lab, not grown in a field.

This diverse galaxy of stimulants—which includes MDMA, speed, meth, LSD, synthetic cannabinoids, mephedrone, fentanyl, carfentanyl, and many more—will be relatively unaffected because much of it is far less dependent on the growth of specific agricultural crops.

Synthetic opioids, especially, have been responsible for a tidal wave of recent overdose deaths. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control estimates that 36,000 people died from synthetic opioid overdose in the U.S. in 2019, including from fentanyl, a drug 80-to-100 times stronger than morphine.

So as you contemplate the end of the world, just remember that coffee and beer may be in ever-shorter supply and growing more expensive within a few decades—but that the world’s supply of killer fentanyl may be just as robust as ever.