This article originally appeared on VICE Netherlands.

In December 1883, Hendrik Frankhuizen – a man from a seriously poor neighbourhood in the Dutch city of Leiden – went to the doctor after experiencing unbearable pain for several days. By this point, his newborn son and wife had already died from incessant diarrhoea and vomiting. The death of a mother and child wasn’t uncommon back then, especially where the Frankruizens lived – a neighbourhood where cholera (which causes similar symptoms) often reared its ugly head.

Videos by VICE

Frankhuizen was experiencing the same illness as his late family, but managed to make it to a doctor. Wijnand Rutgers van der Loeff recognised Frankhuizen’s symptoms: Earlier that week, he’d seen another patient with the same complaints who lived on the same street. A suspicion dawned on Rutgers van der Loeff: Was someone poisoning the people of the neighbourhood?

Sadly, Frankhuizen couldn’t be saved – he died 11 days later in a nearby hospital. But his case kicked off a police investigation which quickly found a potential, yet highly improbable, suspect: 44-year-old Maria Swanenburg, locally known as “Goeie Mie” (“Good Mie”) due to her caring and trustworthy nature. Swanenburg was also Frankhuizen’s sister in law.

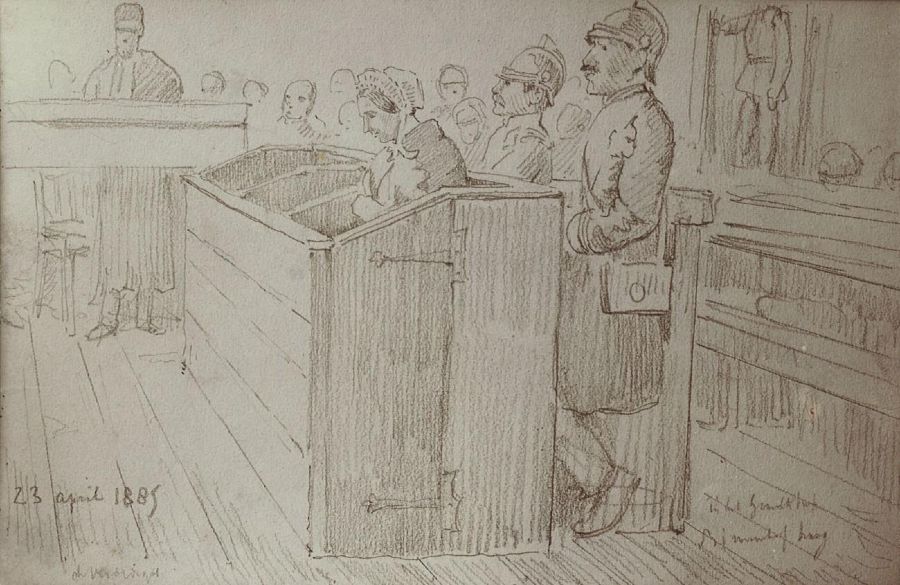

After Swanenburg was declared a primary suspect, other neighbours came forward with stories of different families she’d been involved with whose members suddenly died, one after the other. Overall, Swanenburg was convicted of murdering 23 people, but is suspected of killing more than 100.

Historian Stefan Glasbergen wrote Maria Swanenburg’s story in his book Goeie Mie: Biografie van een Seriemoordenares (Good Mie: Biography of a female serial killer), published in Dutch in 2019. “You can learn a lot about that time when you look at history through her eyes,” Glasbergen says.

Swanenburg’s story began on the 9th of September, 1839 in the city of Leiden. Born into a poor family with many children, some of whom died young of cholera, she ended up living in a small workers’ cottage with her 11 family members.

“You entered through a tiny front room and that was where her parents slept,” Glasbergen explains. “In the back of the house there was a small kitchen, but they often cooked outside. The kids slept on the first floor, right underneath the roof. That space was not insulated; when it rained, it got wet; when the wind blew, you felt it inside.”

Swanenburg’s father had difficulty holding down a job, so the family was always struggling. When she was 12, they fell behind on rent and lost their home. They moved to the Singelstraat, a rough neighbourhood full of the poorest workers in the city. “The neighbours who later testified during the criminal trial said that the girls never really went outside,” Glasbergen says. “They’d knit clothes all day long, which would later be sold.” That was all perfectly normal back then, though, he adds.

Because of her circumstances, Swanenburg probably barely went to school. “We know she couldn’t write, because she put an ‘X’ on her marriage certificate,” Glasbergen says. When she was 28, Swanenburg married the father of her children, who were born before the couple made it official. Later on, this aspect of her life became fuel for gossip and speculation.

“Because she had children before marriage, she was deemed sexually promiscuous,” says Glasbergen. “But there’s no evidence of that. It’s just that, since she’s a serial killer, people assumed she failed ‘as a woman’ in other ways as well.” It’s also hard to tell what Swanenburg’s relationship with her husband was like. He testified during her trial, but the transcripts were later lost in a fire. “There’s no reason to believe there wasn’t affection between the two of them,” Glasbergen notes.

Soon after she married, two of her children died. She was later suspected of poisoning them, but according to Glasbergen’s research, they likely died of cholera. “Whatever Maria tried to do, she couldn’t escape the misery that had been following her since she was a little girl,” Glasbergen adds. After their death, Swanenburg developed a drinking problem. Soon after, she started poisoning people.

In the early days, Swanenburg’s murders were financially motivated. Sometimes, she’d manage to be included in somebody’s will before killing them. She also murdered people she was indebted to, but her main way to profit from the killings was taking out funeral insurance on her victims. Back then, anyone willing to pay the fee could do it – not just family members.

This type of insurance was very common with poor families who couldn’t afford to pay for a burial. At the time, you could even take out multiple funeral insurances on one person. The first insurance fee would be used to cover the costs of the funeral, while the payments from the second or even third insurance could be used as a financial buffer, while the family’s income was being re-arranged. That’s the money Swanenburg would pocket.

“Neighbours were much more likely to help each other in those days and Maria was well-respected,” Glasbergen says. “If you needed someone to look after your kids or do your laundry, you could go to Goeie Mie.” As a result, Swanenburg was often in other people’s homes, which allowed her to gain her victims’ trust and poison them behind closed doors. Her method was simple, she’d just add arsenic – which was widely used for pest control – to the victims’ food and drinks.

The chemical is extremely toxic – when ingested, it causes severe diarrhoea, which in turn can lead to fatal dehydration. When arsenic ends up in your bloodstream, it also damages the organs. Once in your brain, you begin experiencing agonising headaches and light sensitivity. In the end, your heart and kidneys give out. “It’s a very painful death,” Glasbergen says. “Eye witness accounts from people who saw family members die are truly horrific.”

Although the initial murders were committed to improve her financial situation, at some point, Swanenburg’s serial killing became some sort of compulsion. Once, after murdering two sisters she was babysitting, she even poisoned the coffee she offered their relatives at the wake. “They survived, but she attempted murdering six people, including the pregnant mother of the dead sisters,” Glasbergen says.

But with so much sickness and death occurring all around her, why did nobody sound the alarm? “People in that neighbourhood were used to death – children often died and there were many epidemics, partly due to the city’s lack of sewer system,” Glasbergen says. “Hardly anybody lived to be old.” Besides, doctors were mostly too expensive for working class people. Often, they wouldn’t even show up when called. That’s why, for a while, nobody knew what people were dying of – all that changed with Hendrik Frankhuizen.

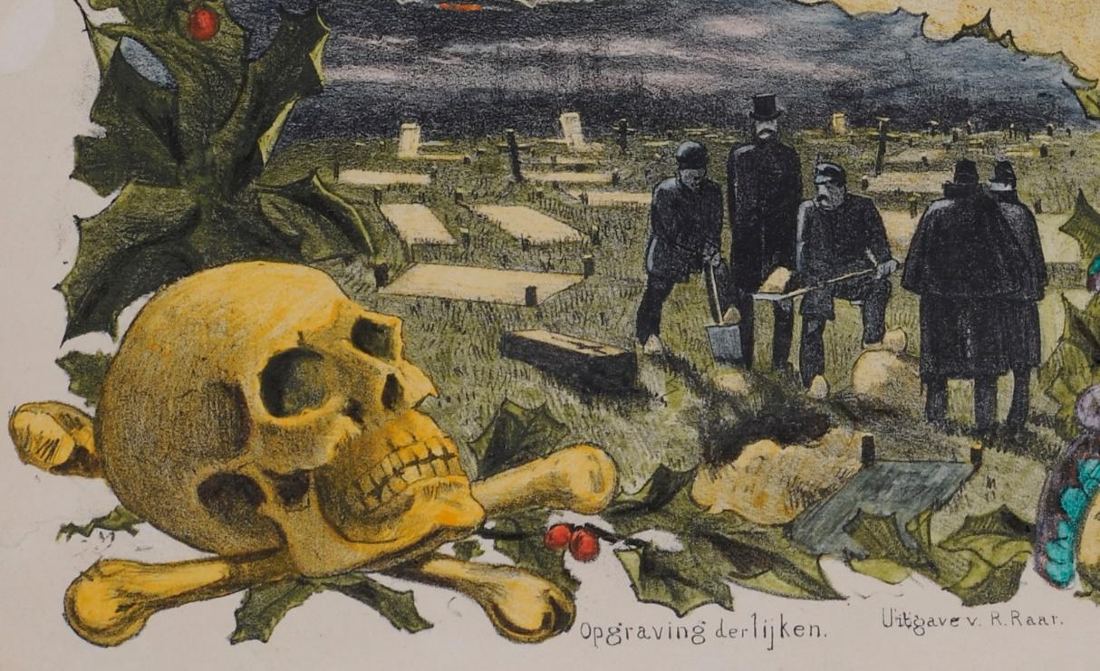

After Swanenburg was arrested, the police found multiple insurance policies in her name and became suspicious. They talked to several people who’d been involved with her and had family members subsequently die, and exhumed bodies to test for traces of arsenic – it was found in dozens of bodies. In the end, she’d poisoned around 65 people she knew and 23 died, though her suspected victim count is much higher.

That was a big contrast to the image she’d built in the neighbourhood, so much so that people were mad at the police when they first arrested her. “Once her deeds were made public, though, everyone had something to say about her,” Glasbergen continues. “There was a big sense of disgust in newspaper articles, but also an oddly sensational tone.” The small house she and her family lived in became a landmark. “There was even a sign outside,” Glasburgen adds.

And her husband? It looks like he dodged the bullet. “He was arrested, but set free soon after,” Glasbergen says. “The media painted him as the victim of an insane woman.” Still, it’s unclear how much he knew, especially since there were so many attempted poisonings and deaths in his own family – and Maria raked in a few yearly paychecks through those insurance policies. “How could he not have been aware of this?” Glasbergen wonders.

Swanenburg’s arrest caused a big stir. The laws regulating arsenic sales were amended, and many journalists and intellectuals supported bringing back the death penalty just for her case. In the end, Swanenburg died in prison in 1915, after 20 years of incarceration.

But to Glasbergen, the most interesting thing about Swanenburg’s story is how much it tells us about urban social oppression in the Netherlands at that time. “Every stereotype from life in that period – disease, poverty, inequality – is present in her story,” Glasbergen says. “Her choices were fundamentally wrong, of course. But I can’t help but wonder: Would she have done the same things in current times, with a much better social safety net? I actually don’t think so.”