One evening Marie opened her younger brother’s Oliver’s bedroom door to bring him a mug of tea. She was met with the typical stale smell of urine, cigarette smoke and alcohol, and the audible buzz of men shouting from her brother’s gaming headset. As she crept to the window with the intention of opening it, her brother shouted “rape her” and laughed that bitches need to be raped and disposed of.

Marie looked at the 20-year-old in horror, as he’d never spoken like this before. He didn’t acknowledge her when she placed the mug next to him.

Videos by VICE

Over the next few weeks Marie – who requested anonymity for both her and her brother due to concerns for their safety – set out to monitor Oliver. When he was gaming, she’d listen outside his door to what he was saying semi-ironically over the headset. Along with slurs and typical internet 4chan slang she knew like “triggered” and “cuck”, she noted a few she didn’t, including “foid”, something she discovered was an incel term for women (“female humanoid”).

She also overheard Oliver debating rape statistics. “He was talking about how men were always being falsely accused of rape,” she remembers. “Feminists were liars and not to be trusted. I was thinking how horrible this was specifically because we’d had discussions with my mum and him about how I was sexually harassed as a girl.”

Marie told their mother what she had learned about her brother. The two women waited until Oliver came downstairs and steered him to the kitchen table for a discussion. Marie tentatively talked about what she knew about feminism, but Oliver became so incensed by the debate he threw a glass tumbler at the wall over their heads and charged to his bedroom. They didn’t see him leave the room for two days.

Half of young men in the UK now believe that feminism has “gone too far and makes it harder for men to succeed”. These are the results of a significant study published in July 2020 by anti-extremism charity HOPE not Hate. The study, Young People in the Time of COVID-19, surveyed 2,076 16- to 24-year-olds on their ideological beliefs.

A growing number of experts across the fields of feminism and anti-extremism were already worried about a young male backlash against young women and their socio-political gains before the pandemic. In fact, HOPE not hate pursued this line of enquiry due to the troubling rise of anti-feminist sentiment they’d noticed among this age group.

Reading this might leave you wondering: what is happening to teenage boys and young men?

“Sexism in classrooms is nothing new, but the kind of distinctness of it being anti-feminist is something that we’ve seen in the classrooms, in our online tracking work,” says Rosie Carter, a senior policy officer at the charity.

She explains that much of this represents the younger and younger recruitment of boys by the alt right and generalised spread of its ideology across social media and the internet. “The number of issues that the alt right will talk about and look at has grown, and it’s all part of a wider pushback against progressive norms – and in some ways it’s scariest because of its mainstreaming.”

From “incel lite” culture – in which men wouldn’t identify as incels come across and potentially engage with related material – to far-right grooming, elements of online life are having a broadly unexamined negative impact on the ways in which boys and men think and engage in the real world.

§

“Men are trash” has been a popular phrase and a hashtag since 2016 and since then, millennial and Gen Z men have challenged what they see as its reductionism. Meant originally by girls as a deliberately provocative throw-away statement is taken for, as one Urban Dictionary entry puts it, “a generalising and hateful phrase coined by a movement claiming to fight hate and bigotry”.

Ted, a 24-year-old from Kent, told me he might have felt sympathetic towards feminism before, “but when you get put in the same bracket with the whole ‘men are trash’ etcetera, then you think what’s the point?”

Reddit men’s rights forums are littered with similar origin stories from young men: “I used to identify as a feminist but left the movement when I asked if there are any disadvantages men face. Instead of answering the question, people started taking shots at me,” one wrote. Another noted: “I could not understand the group hating.”

What Carter found interesting about the HOPE not hate study results was that young people now were found to be more progressive than previous generations in the ways we stereotypically understand the cohort. They are widely pro-immigration, multiculturalism and are supportive of all sexuality and gender identities. “But it was distinctly feminism,” Carter says. “It’s an ideology that boys are pushing back against, in the midst of changing social norms.”

In all the public attitude research she does around the far right, “it always comes down to this idea of fairness”.

“If you’ve always been at the top of the hierarchy, and suddenly someone’s saying, ‘that’s not how things should operate, your sense of fairness is tipped and you start looking for answers,’” Carter says. “Men feel that they have to suddenly work twice as hard because they have to prove themselves.”

The context leading up to this point matters: Millennial men’s reckoning with feminism happened hard and fast. It had to – it arrived in conjunction with that of millennial women. In the early 2010s, both millennial and feminist discourse were characterised by lad culture, which predominantly appeared in conversations about male students and university. Its more minor iterations were hyper-masculinised group banter and exposing your genitals when pissed. At worst, it was casual sexual harassment, assault and rape.

Meanwhile, a booming digital media industry published young women’s voices on anything affecting them from emotional labour to abortion, amplified by an emerging age of social media. By the mid-2010s, layoffs and publication closures across the industry meant an already dying men’s media took a significant hit. In the UK, FHM, Nuts, Zoo, Shortlist and Front folded and the digital publications that were by lads for lads – Unilad, LADbible – were forced to change.

Whether all this meant lad culture died – rather than warped and diverted elsewhere – is up for debate. Hussein Kesvani, a technology and online subculture journalist, argues: “I don’t know whether lad culture has died; rather the general consensus is that you shouldn’t try to market it.” He notes that Unilad, LADbible, joe.co.uk have lost their identity: “They tried to keep lads on board but present themselves as socially aware and progressive. That model had a short half-life and just isn’t resonant now.”

In 2018, #MeToo provided women with an opportunity to talk about sex, dating and rape culture. Arguably, it also provided men in their 20s and 30s at the time to reconcile their own behaviour and review their encounters with women. It suggested a symbiotic relationship: Women speak, and men listen and are able to understand their masculinity through this outpouring.

Whether it was ever that simple is increasingly questionable in hindsight. Were there enough spaces for the average man to consider his own gender role? Did straight men even care? And if what it meant to be a millennial woman defined what it meant to be a millennial man, where did that leave younger generations?

When writing an article back in 2019 in which I spoke to teenagers about #MeToo, I found that they felt they weren’t part of it, and didn’t know what it was or how it affected them. Recent feminist battles have included the gender pay gap and workplace sexism, which are unlikely to register to a generation coming of age into unemployment, freelancing or wannabe entrepreneurship.

Millennials were the last generation to genuinely care about men’s publications. For at least half a century, men’s media set the goalposts for behaviour. When it died in the 2010s, the vacuum was filled by brands and social media – where masculinity is only ever implicit or rarely addressed – and incel and alt-right adjacent culture.

For Kesvani, the issue of anti-feminist boys stems from the fact there’s no real blueprint from men’s media or society-at-large for how to be a young man now. “The lack of blueprint is to do with economic and material reasons, but also cultural reasons too, and cultural reasons can be so hard to define.”

§

Before the pandemic, women’s rights campaigner Laura Bates visited one or two schools a week to speak with students about gender inequality. For a decade, the responses would range from shock to giggles, but on the whole, pupils of all genders would be attentive and engaged.

A couple of years ago, something changed: A boy sat in the front row, noticeably nervous but excited. Through Bates’s usual routine, he gleefully interrupted to debunk what she was saying with false statistics about rape and claiming men were more likely to be victims. This became the new normal.

“Boys were arriving pre-prepared, pre-conditioned almost and they often had things written down that they’d brought with them as if they were primed in advance,” she says. “The same arguments were appearing everywhere from inner city London to rural Scotland.” The arguments were factually incorrect, amounting to little more than conspiracy theories and fake news – incorrect ideas and figures about the gender pay gap, false rape allegations and men being more likely to be victims of domestic violence.

Bates began to ask the boys where they were learning this material. They always told her “online”. They showed her memes, images and jokes that weren’t obviously or directly from manosphere communities but regurgitated their ideologies.

This material is so readily available online that it’s practically an omnipresent part of existing in certain areas of the internet – part of an incel lite culture that is almost post-organisational. The online growth of the far right is a significant problem not least because of, as is Bates’ main concern, the number of “neutral boys” – ones who aren’t on men’s rights forums or actively feminist – who are being swayed by the more extremist ideas about women without realising it.

Another problem is that extremist groups are accessing boys at younger ages. “I’ve read manifestos from leaders of these communities explicitly saying boys as 10 or 11 ought to be their main targets, describing the use of memes and images as a delivery system to get these misogynistic ideas to take hold,” Bates says.

The boys and men she interviewed for her latest book Men Who Hate Women were as young as 11 when they became involved with such communities on 4chan or YouTube by “going down algorithmically supported rabbit holes” until they reached darker content.

One popular method of teen recruitment is through gaming. Recruiters use sites and games as a “hunting ground”, Bates says, since this is where young men are gathering. “They can reach them without supervision, particularly boys who are playing multiplayer online games over headphones with people they’ve never met before.”

Bates describes the method as subtle: “They start by dropping sexist jokes into the conversation to see if they’re receptive and escalate it to private chats, which are obviously meant for people to share gaming tactics, but they’re using them to groom boys and eventually direct them to these more extreme communities.”

Marie and her family are convinced this was how Oliver was targeted. Soon after he began speaking with his new gaming friends every night until the early hours, Marie says his behaviour changed and they started “losing him”. He told Marie that his friends were men from all over the world, mostly older, refusing to provide any more information.

If we consider that the far right spans incels, men’s rights activists, pick-up artists as well as neo-Nazism and alt-right splinter groups, women-hating can be a way to recruit across the board. HOPE not hate found in their study that the young men who feel that feminism has gone too far were also twice as likely to think that jokes about race or religion were acceptable and twice as likely to think that discrimination against white people is as big a problem as discrimination against Black people.

“The far right has increasingly spread, the number of issues they’ll talk about and it’s all part of a wider pushback against progressive norms,” says Carter. Similarly, once you’re within the far-right, that allows you to engage in hate towards other communities. Activists in different groups will feed boys into the others, referring them along.

John, 21, was radicalised by the far right when he was in his late teens. He spent two long years in his bedroom in the north of England learning about far-right ideology online and trolling feminists. Mostly he would infiltrate feminist groups or use multiple anonymous Twitter accounts to verbally abuse or harass women any time anything to do with women or feminists were trending or performing well on the platform.

“We knew we could wind them up and provoke those groups easily,” he says today. “This is gonna sound really daft, but I don’t think it was anti-feminism. I was just bored and that was the person I was then. It wasn’t that I had a really aggressive mentality towards women or really hated them, it was just about causing a riot.” No one explicitly told him to do it, he says – it was just part of the online culture he grew up in.

John has his own theories about why boys are successfully groomed by the far-right more than girls. Stereotypically, he thinks boys are angrier, and seek release of anger and frustration. Some do it at football matches, others by participating in sport. “But some lads never find that release, so a lot of the time people join the far right just because they’re angry about a situation and don’t know what to do with that frustration. It isn’t just about hating a certain type of person. At times, it can be a cover for something else. And that cover is the worst thing possible.”

§

How do you deradicalise an anti-feminist? It’s a painstakingly delicate and complex process. At Exit UK, the leading organisation in the UK for supporting those wanting to leave the far right and their families, every boy or young man will be matched with a mentor. The mentor will deconstruct their ideology slowly over a series of sessions. What they tell boys with woman-hating ideology is simple: What does your mum or sister do for you on a personal day-to-day level? Then they ask: How would you feel if men were talking about your mum or sister in the way you do?

But one false step from the mentor and that young man is lost. Exit UK say those that leave are never seen again and very likely return to their hateful community with a hunger to become more extreme.

There has been an explosion in referrals over the pandemic. Although involvement with the far right will differ from referral to referral Exit UK had 90 people contact them over 2019. From April of 2020 to February 2021, they had contact with 350 people seeking help.

Nigel Bromage, the founder of the company and a former far right member, says he commonly sees a mix of internet irony, 4chan humour and one-upmanship in what boys do and say. “Forums will start with sick comments and become more extreme, so by page eight they’re talking about using rape as a weapon to degrade women.”

Lonely young men without girlfriends are prime targets. “They think ‘I’d like a girlfriend’ and the far right says ‘Well, you can’t get a girlfriend because all the girls have become feminists and left wing.’”

Sometimes referrals come from a young man directly who is aware that he has become brainwashed. Often it will be a family member who refers the younger boys. Sometimes a school will refer them. When John’s mother Sarah realised her son had been radicalised, she spoke to a teacher she trusted who watched for signs of him recruiting others at school. Then that teacher, with Sarah’s permission, was able to call Exit UK for a referral.

The strain on families with a radicalised family member is significant, and that’s before considering the potential danger family members themselves are in. Sarah says that John even made an attempt to radicalise her, trying to draw her in with far-right information at home. When she disagreed with him or challenged his views, he’d become angry and agitated.

“Many, many nights I lay awake thinking, am I the cause of this?” she says. “Every mother with a child that’s been involved with the far right in some way does question themselves and feel responsible. It’s sad because it’s not their fault, it’s the far right – they’re very manipulative and selective.” Exit UK has a family support programme to help families and teach them how to have difficult conversations with the radicalised member, who can become angry when confronted.

Sarah remembers waiting at home when John was having his first meeting with his mentor. “I expected him to go off the wall and was waiting on tenterhooks all day for that call to say he’d lost his mind.” Instead he returned and they had the first proper conversation Sarah can remember having with her son in years.

Today John is polite, his tone bright and friendly down the phone. He describes the relationship he had with his mentor as empathetic and honest. “There was no predetermined mentality about me. With other people, I felt like they were already judging me and had a default view about me because of the views I had.”

Bromage says that mentors are trained to temporarily remove themselves from a difficult conversation if they don’t know how to answer – tell the individual they need to make a quick cup of tea or use the bathroom to give themselves time to plan an answer.

Due to the rising case load over the pandemic, Exit UK is rapidly training more volunteers to take phone sessions. Bromage is currently deeply concerned that the virus has meant he and other workers are unable to meet men in person, as this is where the most effective work is done; in the physical world, away from a screen.

“Engaging online is not the same as a coffee and a chat,” says Bromage. “It’s not as personal, and in many cases it does make things harder to gauge body language, understanding and emotion. Face-to-face engagement helps people relax, they can see those they are speaking to are ordinary people, who simply care and want to bring people away from extremism and danger.”

§

Obviously, not all teenage boys are misogynistic, and Bates is mindful to say that – “but these movements,” she argues, “have taken hold much more quickly and more effectively than our current total lack of societal awareness of them would suggest”.

The effect the pandemic will have had on this issue cannot be ignored. Carter is concerned about the context of the early 2020s, pointing to the interest in conspiracy theories and widespread youth unemployment rates. “Isolation, feeling hopeless, feeling out of control and that things aren’t right – that is the context that we see an increase in people looking to the far right,” she says, adding that work must be done in a post-pandemic landscape around youth unemployment and deprivation.

Hope is an important word. Carter believes change can happen when we collectively challenge the prevalence of extremist material on social media platforms and provide education on the topic at a school-level. The way in which all these different far-right inclinations intertwine towards anti-progressiveness means we shouldn’t just attempt to tackle anti-feminism alone, either. Teaching should address issues of racism, anti-semitism, violence and misinformation.

Sharing the story of her son’s extremist views with the school was what gave Sarah hope. “Do not sit on it or try to deal with it on your own,” she advises others in her position. “By doing so you’re allowing the far right to tighten their grip on your child.”

At the end of our call, Bates and I talk about one of these anti-women communities whose information is reaching boys, Men Going Their Own Way (MGTOW). Level one of their plan for separatism from women involves rejecting marriage and cohabitation, level two rejects long-term relationships with women, three rejects all relationships with women, four is a refusal to do more than necessary for survival and avoid taxation wherever possible and five is to drop out of society altogether.

Doesn’t this map perfectly onto how someone retreats into their own shell by spending vast amounts of time online, I say. Bates agrees: “I think the tragedy is that if you were on that path there might be real opportunities for intervention. Communities seize upon very real issues, one of them being male mental health. These issues make it much easier for the manosphere to pull them in and to take away their hope.”

More

From VICE

-

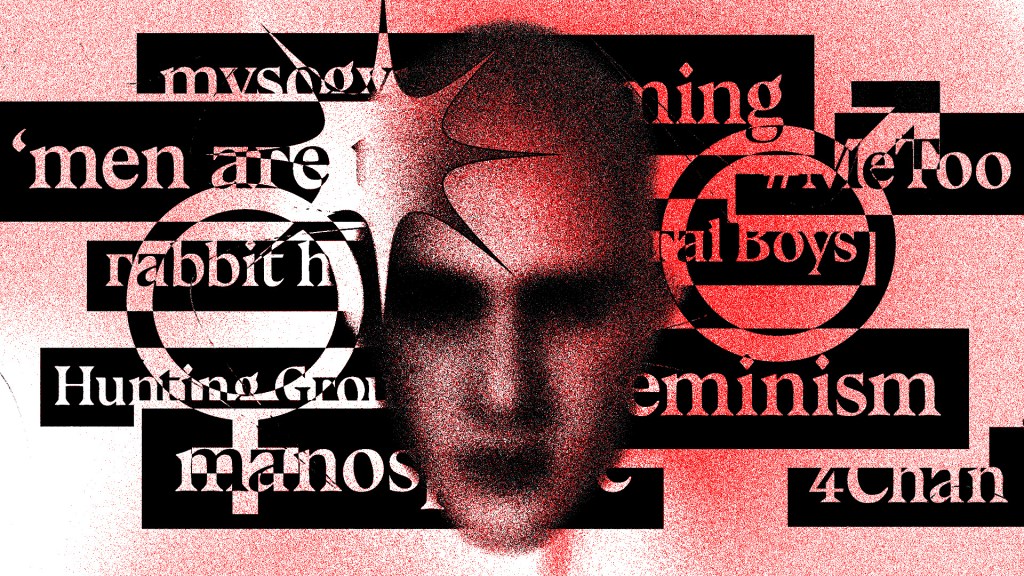

Collage by VICE -

Nick Fuentes, a white supremacist streamer and US social media pundit, appears to mace 57-year-old Marla Rose, a 57-year-old on his doorstep on Sunday, November 10 (Imagery courtesy of Marla Rose) -

(Photo by Carl Court/Getty Images) -

VICE