The consumer electronics we use everyday often don’t degrade well. A landfill is a terrible place for old smartphones, televisions, or computers. Electronic waste can be composed of heavy metals, rare earth metals, and other potentially hazardous material. Much of it is hard to recycle, and disposing of e-waste is costly and dangerous. So, for decades, Europe and the United States have shipped e-waste to Africa and Asia, sometimes illegally. In a new twist on an old problem, Europe is starting to hide some of those electronics inside used cars.

The European Union has laws against exporting e-waste and dumping it in Africa, but the problem persists and, according to a new study, Nigeria is one of Europe’s prime dumping grounds. The United Nations University (UNU) and the Basel Convention Coordinating Centre (BCCC) for Africa partnered co-authored the study and found that 66,000 tons of used electronics shipped to Nigeria contained 16,900 that didn’t work.

Videos by VICE

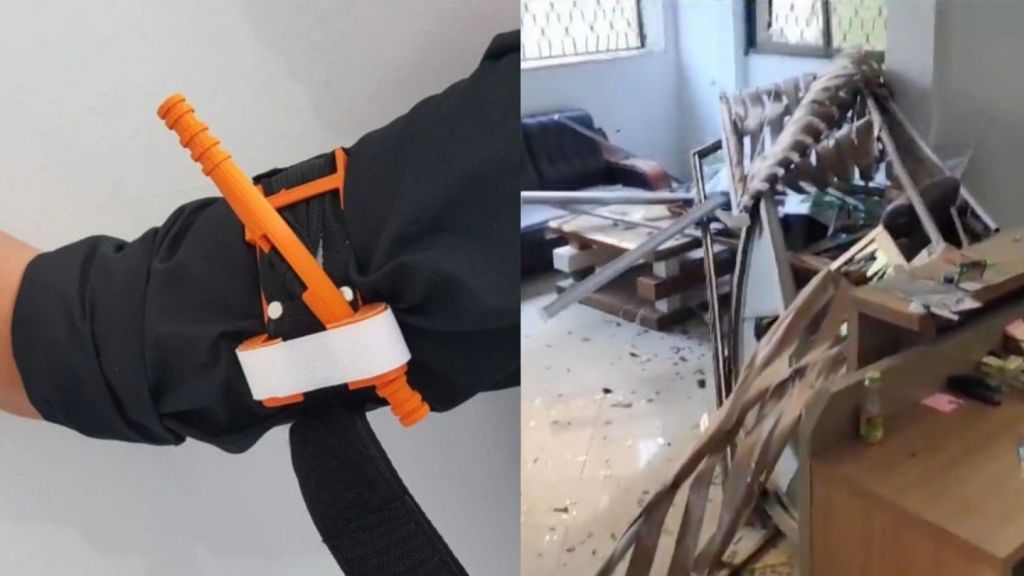

Shipping non-functioning electronics from Europe to Nigeria is illegal but lax enforcement and clever importers skirted inspectors by loading up used cars with electronics then shipping it across the ocean. “To our surprise, the most important import route was not the containers but the roll on / roll off motor vehicles,” Otmar Deubzer, an advisor at UNU and co-author of the study, told me over the phone. “Around 70 percent of equipment came in via this route.”

To be clear, not all old electronics coming over are bad, and Nigeria does want some of them. “It’s very important for us to distinguish between used electronic equipment and waste electronic equipment,” Percy Onianwa, a BCCC Africa official and co-author of the study, said over the phone. “What is prohibited is the export and import of the e-waste, the non-functional equipment. It is still allowed to import used electronic equipment.”

Nigeria has a population of almost 200 million people and a booming market for secondhand electronics. “It’s a very good market for those who want to make some money shipping used electronic equipment,” Onianwa said. “Unfortunately, much of it is broken down or end of life.”

The e-waste problem is complicated. Nigeria wants functioning equipment, but it doesn’t want waste.

Onianwa explained that Nigeria also has a robust used car market and that exporters are “stuffing their vehicles with electronic equipment, that way it saves them space and money. Instead of having a car where space is free, you can stuff them with this equipment and therefore you’re paying for containers. Some of them find the regulatory agencies aren’t looking in that direction.”

“The manufacturers should be thinking of designing the equipment in such a way that the equipment can last longer”

Waste product that ends up in Nigeria is often cannibalized for parts. What can’t be recycled or repurposed is often dumped into landfills and set on fire. That’s a problem because many of these used electronics contain heavy metals, organic material, and rare earth metals that are hazardous to human health.

“We’ve got lead, mercury, cadmium in there,” Jim Puckett of the Basel Action Network, a nonprofit that works to promote environmental causes related to e-waste, told me over the phone. “A lot of [the imports] described in this study…have mercury backlights. These are LCD screens that, before LED screens were in widespread use, used mercury lamps at the backlight…when you smash it apart, you breath this mercury.”

Another problem is the definition of “functional.” While many of the imports are technically reusable, they’re often out of date or barely operational. The UNU researchers spent 10 months inspecting shipping containers, and 16 months pouring over import documents. They opened up 200 containers and tried to use the devices they found.

“Around 20 percent didn’t work,” Deubzer said. “The actual rate is probably higher but we couldn’t go into detailed tests on site. We could, for example, check whether a TV would start…we could not check if it would stop working [after a time.]”

This problem gets thicker when you open a shipping container filled with, say, thousands of mobile phones.

“[Authorities] can not test every phone,” Rüdiger Kühr of the UNU, said over the phone.

The laws against import and export of non-functioning e-waste largely carry monetary fines. And Onianwa explained that Nigeria has enforced the laws, which led to fines of some importers and the return of the e-waste to its country of origin at the cost of the importer. In Europe, enforcement is harder.

There’s too much money to be made and not enough incentive to stop. “If [the exporters are] discovered illegally shipping e-waste, it’s a risk they’re taking because the penalty is usually only monetary,” Kühr said. ”The work force the port authorities is small. The chance of being [caught] is minimal.”

To combat this problem, Europe and other countries have to step up enforcement. But ultimately the original manufacturers of smartphones, TVs, and laptops need to step up as well. Many tech products we use everyday aren’t designed to be easily reused or recycled. “The manufacturers do not pay attention to green design…they don’t design products to be toxin free, to be upgradeable, to have a long life,” Puckett said. “There’s no incentive for them to go there. It’s designed for the dump and that’s where it ends up.”

On this note, though, Onianwa and the team at UNU and BCCC Africa are hopeful. “The original equipment manufacturer have a lot to do and they are begging to do it,” he said. Manufacturers such as HP, Philips, and Samsung are beginning to take responsibility for their part in the e-waste problem. “They are beginning now, in Nigeria to work on a scheme that will require the original equipment manufacturers to take charge of the e-waste problem… [The manufacturers] should be thinking of designing the equipment in such a way that the equipment can last longer.”