As road crews in Alaska worked overtime to repair damage from a major earthquake on November 30, some 1,500 miles to the south, flyers lined the streets of the Mexico City neighborhood of La Condesa, touting an egg-shaped, life-saving capsule containing enough food for a month, should disaster strike.

The cost? A cool $10,000 USD for the top of the line model.

Videos by VICE

While neighborhoods such as La Condesa and Roma, where the 7.1 magnitude Puebla earthquake in September 2017 caused the most significant damage, continue to rebuild, there are still a handful of wall-less, half-standing buildings, through which passersby glimpse into empty apartments. Other structures remain in piles of rubble. But a young Mexican engineer thinks he has a partial solution to what he and others say is inevitable: the next big quake.

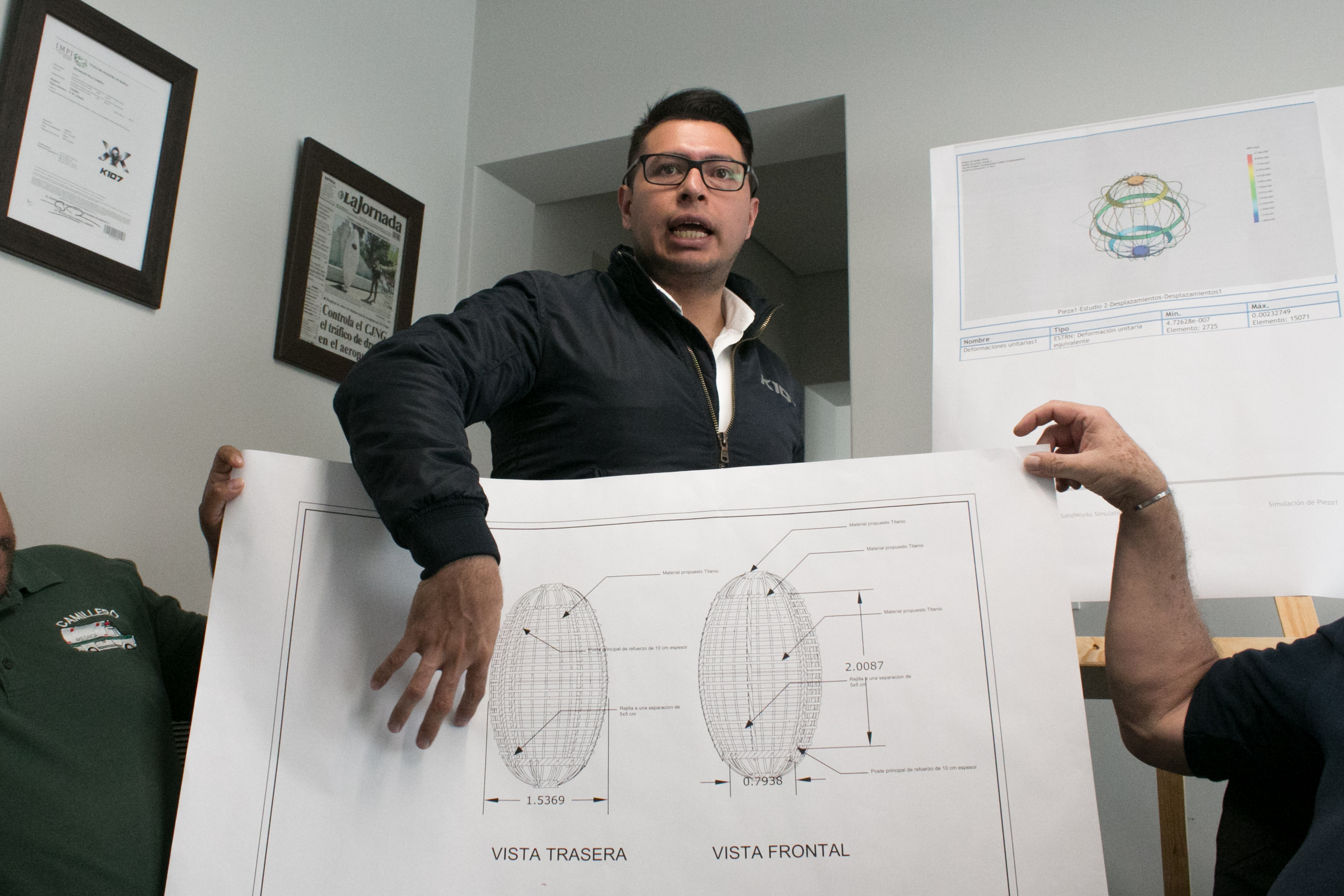

The answer, according to 32-year-old engineer Reynaldo Vela, comes in the form of a high-end “egg” currently being marketed to the rich and corporate clients. When you feel the ground start to shake, simply hop into the egg, close the latch, and you’ll be safe, even if the building collapses on top of you. At least that‘s the pitch.

As El Universal reported earlier this year, the capsule, replete with seismic alert sensors and a GPS beacon, has been approved by the State of Mexico, the National Council on Science and Technology, and the Atzcapozalco campus of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, as well as “several laboratories and private organizations.“

The question, however, is whether the slick capsule will become a fixture in the corners of living rooms and offices of Mexico and beyond. As one longtime resident suggested, the device is simply too morbid—a glistening coffin from the future.

The egg, named Capsula K-107, has been in the works for eight years, Vela told me recently in an interview at his company’s office. Prior to the September 2017 quake, Vela added, only three of the capsules had sold. (A fourth unit, which he did not purchase, was in his own home, though he was out when the temblor hit.) Since then, he said he’s sold more than 110 of the units, with a waitlist that has resulted in a three- to five-month delay in shipments, all in Mexico.

Vela’s company, K-107, has experimented with different designs and materials over the past eight years of capsule development, but has settled on a prehistoric shape: the velociraptor egg. The exact contours came to the engineering team in the form of a fossil from Timmo Hofman, a Canadian paleontologist whom Vela calls a friend.

“From this, we conducted a special investigation into the velociraptor egg comparing it to the conventional normal egg,” Vela told me, including impact tests at speeds greater than 100 kilometers per hour. (The true test of strength is at the egg’s upper tip, where presumably the floors of a building would be falling onto.) “The normal egg resisted very well, but the velociraptor was much better because it is more convex than a normal egg.”

For the average citizen or family in Mexico City, home to more than 21 million people, Vela’s product is simply out of reach, though it is worth noting, per El Universal, that K-107 donates one capsule to “vulnerable citizens”—senior citizens, for example—for every 10 sold. Meanwhile, most of the capital remains at risk due to its foundation atop a drained lakebed, which is believed to amplify the shaking effects of seismic activity.

Following the 8.0 magnitude Mexico City earthquake of 1985, which killed more than 10,000 people and collapsed more than 400 buildings, the city implemented a strict building code. But when the Puebla quake struck last year, many of the city’s newer buildings, constructed after the regulations were put in place, still collapsed, according to a report from Mexicans Against Corruption, a nonprofit advocacy group consisting of journalists and researchers. The report found that many developers didn’t follow the new building code, and it also blamed some of the collapses on a climate of corruption that allowed cutting corners and costs in construction materials.

Vela and his team, for their part, have taken matters into their own hands, providing a reactionary vessel—for those who can afford it. “A year after these two great earthquakes [of September 7 and September 19, 2017] the population really started to see things in a different way,” said Vela, who formerly served as an engineer for Mexico City. “The focus is to put all your attention to acquire a device to have in your home and really feel safe because we know that another earthquake will happen.”

Vela considers it a growing market. The world is warming, natural disasters are becoming stronger, and barely a day goes by where a fire, hurricane or megastorm doesn’t lead the cable news broadcasts. If anything, much like the intense demand for respirator masks during the recent California wildfires, Vela’s earthquake egg capsule is part of a broader trend in disaster capitalism.

“There may be a tsunami, an avalanche, a landslide or flood, a hurricane or tornado or typhoon,” Vela said, rattling off the looming disasters. “The capsule is going to help you.”

While the focus has been on selling in Mexico for the past year, the team behind the project, which includes Vela’s Italian business partner and designer Flavio Mericio, is looking to expand its initial reach into the US and Canada. During our chat, Vela was eager to point out dozens of emails from potential customers from around the world seeking information on the eggs. Some of the queries he showed me were from residents in other Latin American countries, California, and Canada.

“Very similar to what you expect with the San Andreas [Fault] in California,” Vela said, “you expect in Canada, in Vancouver itself.”

Of the multiple available egg models, the basic version, which is meant for apartments or single-family homes, starts at $2,400 USD and can withstand a collapse of a three-story building, the company claims. The most advanced model, designed for Torre Altus, a 45-story building in the city’s Santa Fe neighborhood, goes for $10,000. The strongest models are constructed of steel and carbon fiber, while other, more basic models are made of a combination of materials, namely resin and kevlar.

“We manufacture the device shield depending on the weight of the building,” Vela said. “All properties are constructed differently. We have properties in ancient Mexico that consist of masonry walls that are very large and very heavy.”

As for conditions inside the eggs, life is not exactly pleasant, though according to Vela, there are supplies that can last an individual up to a month. Moreover, depending on the model and the customer’s order, the egg will contain either one or two seats that closely resemble those of a stand-up rollercoaster where the inhabitants are essentially stand-sitting. The seat or seats are attached to a spring-loaded base that acts as a shock absorber in the case of a fall.

Each bicycle seat-like seat has a hole in the middle with a black bag that hangs below for easy urination and bowel alleviation. This bag contains liquid-absorbing polymers and chemicals to cover the smell of a days- or weeks-old deposit. The capsule also includes an ionizing air purifier and is outfitted with a water vapor condenser that collects liquid in a compartment for drinking. The unit can produce 400 milliliters per day, according to Vela, who said K-107 has plans for an international product aimed to be a life raft for all manner of natural disaster, be it a flood, fire, hurricane, or earthquake.

For now, each capsule is handmade in a small workshop manned by a handful of employees, in the Iztacalco borough near Mexico City International Airport. The company hopes to expand its production capabilities to 1,000 capsules per month, but for the time being can only make about 50 each month, according to Vela.

In an interview with Motherboard in the Capsula K-107 offices last month, Jorge Gabriel Ruiz Albarrán, a member of the famed Topos Tlatelolco rescue squad, called the capsule a “necessary device.” Topos, or “the moles,” formed during search efforts in the immediate aftermath of the 1985 earthquake. At the time we spoke, Ruiz Albarrán had just returned from a trip to the Philippines where he was helping search efforts following a typhoon and subsequent landslide.

Indeed, he and the Topos crew frequently travel the world to assist in rescue efforts, from Taiwan to Indonesia, Italy, and Haiti, and were even on the scene in New York City following the September 11 terrorist attacks. They are experts in locating and rescuing victims in collapsed buildings.

“People will be much more likely to survive and not leave it to chance,” Ruiz Albarrán said of Vela’s earthquake eggs. “It is a device that I think will help a lot.”

Even if it has yet to undergo the ultimate test: a real-life earthquake.

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Sony -

Tulip by Germain -

NVIDIA DIGITS Pre-Launch Image – Credit NVIDIA