When someone reaches a certain level of fame, we stop viewing them as a person. The constant presence of their image – in the news, in conversations surrounding it and in pop culture at large – makes them feel less like a human being who once came out of their mam and yawned through fifth period maths class like the rest of us, and more like a brand; a symbol or slogan that stands for something beyond themselves. The delirious love felt for artists from La Dispute to One Direction has birthed a massive amount of positive change on a personal level (how many times have you heard someone say an artist “saved” their life), as well as some pretty weird but ultimately harmless behaviour, like the time that girl hid in a bin just to catch a glimpse of Niall Horan. But it also has a dark side.

Last year, Justin Bieber quit Instagram (for six long, dark months) and said he wouldn’t be taking photos with fans anymore, writing that things had “gotten to the point that people won’t even say hi to me or recognise me as a human.” In 2011, someone crawled into a hotel ventilation shaft to get an autograph off Ricky Martin; in 2004, a man was sentenced for sending death threats to Michael Jackson; back in 1996, a man stalking Madonna was sentenced to ten years in prison for scaling the fence of her home and threatening to cut her “from ear to ear” if she didn’t marry him. All of which is to say: the exposure that comes with fame can leave someone open to harm, fandom is not always positive, and – because the extreme end of it is so often bound up in mental health issues – the underbelly is rarely addressed well, if it’s addressed at all.

Videos by VICE

The most dramatic cases often appear in the media presenting fans as faceless offenders – “crazed” and “psychotic” – inherently pushing aside any context to their lives beyond their relationship to the celebrity. In 2008, for example, 30-year-old Paula Goodspeed – a Paula Abdul “fanatic” – was found dead in her car having overdosed near Abdul’s house not long after her audition on American Idol was torn to bits. Many of the reports characterised her as a “celebrity stalker“, which her relatives disputed. General discourse has only just begun to scratch the surface of mental health problems faced by musicians, exacerbated by fame, but the more obsessive end of fandom is often polarised as valueless or violent with no nuance in between, or empathy on either side. Which makes it all the more interesting that one of the most accomplished treatments of the issue came courtesy of Eminem – a rapper so disassociated from the concept of empathy he was sued by his ex-wife Kim for releasing a song detailing killing her and then himself the same year she attempted suicide.

The Marshall Mathers LP came out at the end of 2000, a frankly batshit year for pop culture. The Y2K bug shutdown didn’t happen; the age of blogging began; boyband fanaticism reached its peak with NSYNC’s No Strings Attached while Backstreet Boys were still riding hard on Millennium; MTV launched Cribs, giving us a personal insight into the inner lives of the stars then fully distanced from the rest of us by the absence of social media; Britney Spears released Oops, I Did It Again, Limp Bizkit released Chocolate Starfish and the Hotdog Flavored Water, and both artists had such an equally massive impact on the zeitgeist that Eminem namechecked them in the same breath in a song he performed at the VMAs surrounded by lookalikes in an effort to skewer 00s pop culture and his own influence on it. Between the election of George W Bush and the rise of celebrity voyeurism that would birth The Osbournes and The Simple Life, conditions were primed for someone as disruptive as Eminem – an artist Rolling Stone lauded at the time for being “loud, wild, dangerous, out of control, grotesque” and “unsettling” – to succeed. Written largely about his own life, rise to superstardom and cultural forces around him, The Marshall Mathers LP quickly became the fastest-selling studio album by any solo artist in American music history – a record that went unbeaten for 15 years, when Adele released 25 fifteen years later.

“Stan”, a lead single and centrepiece for the album, is one of the most significant moments of Eminem’s career; a track both timeless yet extremely of its time. We all know the story: obsessed fan, Stanley, writes Eminem increasingly desperate letters from within the peroxide shrine of his basement and, before receiving a response, goes full radge. He ties up his pregnant girlfriend, locks her in the trunk of his car and drives into a river, killing them both. The reason it is of its time is because: a) technology has changed the way fandom looks today – “Stan, 2017” would just be a 25-second skit about muting someone who kept furiously tweeting “DIE, TRASH” at their fav; b) it’s built upon a Dido sample and; c) the rampant misogyny resulting in a murder is incidental, merely a side plot to the central relationship between two angry men. We know Stan’s name, we know his brother’s name (Matthew), and we’re told a potential name for his unborn child (Bonnie, after the song “97′ Bonnie & Clyde” in which the concept of locking a mother in a trunk and drowning her first appear). The woman herself is never named, only appearing as “my girlfriend”, “bitch” and a series of muffled screams (normally, Eminem has no problem naming all the women he hates). There’s no way the intended message would have been received the same way if it was released today.

That said, the woman’s lack of identity is also part of what allows “Stan” to retain its relevance. If she were named, “Stan” would immediately refocus itself. It would no longer be about “Stan” as a reflection of a very real type of confused and volatile individual who can’t separate fiction from reality – who can’t separate Marshall Mathers from Slim Shady – but “Stan” as a specific, fictionalised murderer of a specific, fictionalised woman. In naming her, the song would lose its greater meaning and instead become pure horror. There is room for projection, and therefore space for a certain degree of empathy, between graphic violence and anonymity. Whether we should feel empathy for Stan or Eminem is a different question, but in many ways “Stan” is less about the lines themselves and more about what’s going on between them.

“Stan” exists as a cautionary tale to fans about taking everything your idol says literally, as well as an examination of our tendency to lay the responsibility of a tragedy at an artist’s doorstep because that’s easier than addressing any deep-rooted societal issues that may actually have caused it in the first place. It’s Marilyn Manson being blamed for Columbine without talking about gun control, Judas Priest and Ozzy Osbourne being implicated as catalysts for teenage suicides without addressing the societal conditioning that can prevent young men from speaking about their problems, and it’s Theresa May banning Tyler, the Creator from entering the UK for “posing a threat to public order” because of homophobic and sexist lyrical content then, two years later, striking a £1 billion deal with a political party who staunchly oppose same-sex marriage and abortion. “Stan” is ostensibly about a relationship between two violent men, but it also asks us to consider the relationship between art and reality. It’s about culpability, idolatry, and the doomed result of dumping a complex mass of problems onto one specific set of shoulders (whether that’s Stan’s problems on Eminem, or a society’s problems on celebrities in general).

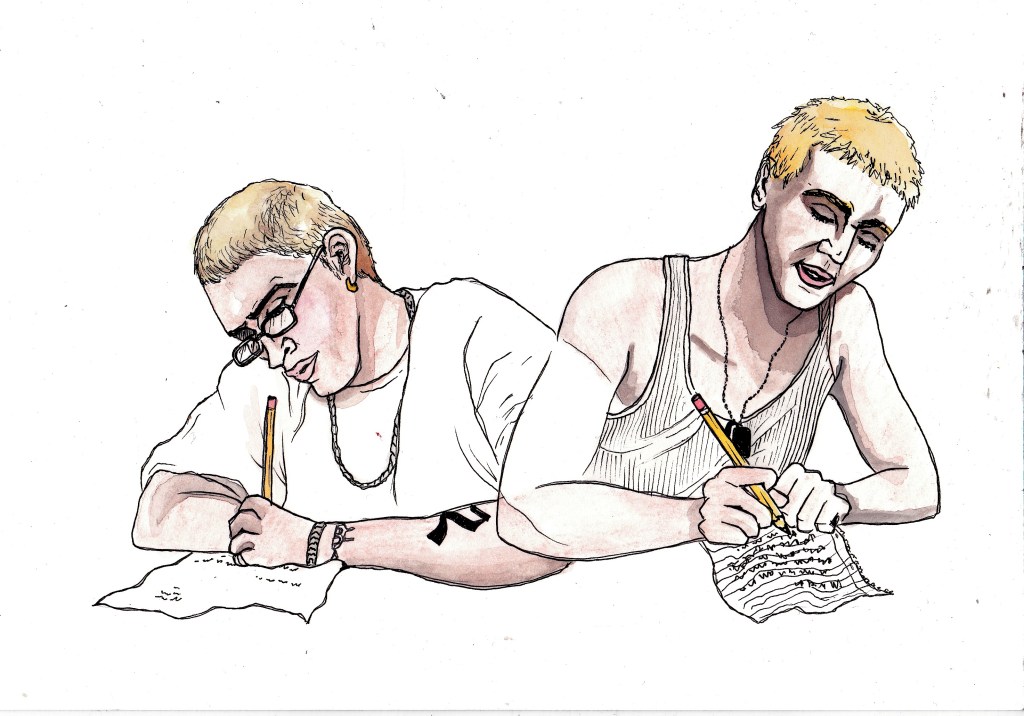

Opening with a sample of Dido’s “Thank You“, “Stan” is full of background noise: pencil scribbling on paper, thunder and rain, windscreen wipers, screams. It’s essentially a play, a Shakespearean tragedy in four verses. It pushed the boundaries of what rap could do, narratively, and challenged critics who felt that Eminem’s popularity was couched exclusively in shock value. Eminem has spent plenty of record time directly engaging with negative public opinion through his raps, firmly rejecting the role of a role model and defending his right to say and do whatever he wants, but “Stan” is different. On the track, Stan only ever addresses Eminem as “Slim”, while Eminem – seen writing with glasses on and everything, like a respected author at a book signing in Waterstones – is positioned as the comparatively measured and polite voice of reason, subverting absolutely everything he was otherwise communicating to the public as Slim Shady. He doesn’t sound angry, he’s not putting on a dumb voice or making jokes, there’s no rapidfire wordplay – but that’s because it isn’t Slim Shady, and it isn’t Eminem. It’s Marshall Mathers, making a rare appearance to not incorrectly suggest that Stan stop worshipping him, get some therapy and treat his girlfriend better.

That’s not unintentional. The track is an anomaly in that it’s one of the few that didn’t unfold conceptually as it was written. “‘Stan’ was one of the few songs that I actually sat down and had everything mapped out for,” Eminem told VH1 in 2002, “I knew what it was going to be about”. The idea came after he was sent the beat by producer The 45 King, who heard Dido’s “Thank You” on an advert for Sliding Doors, taped it off the TV and added beats and the bass line. “Her words instantly put me there,” Eminem said, “‘Your picture on my wall’ – this is about an obsessed fan. That’s all I kept thinking.” Later, Dido was sent a letter informing her that her pick-me-up song about a pretty shit day had been sampled on a murder ballad – and she was into it, which is probably a testament to how hard both tracks slap instrumentally. It was and remains one of music’s most unusual partnerships: America’s Most Wanted and nan’s-radio-friendly English Rose; “Cum On Everybody” and “White Flag“; Marshall Bruce Mathers and Dido Florian Cloud de Bounevialle O’Malley Armstrong. Still, it worked. “Stan” was number 1 in 11 countries, including the UK, Germany, Ireland and Australia. It’s widely considered to be one of Eminem’s most critically acclaimed songs, with Rolling Stone naming it one of the best songs of all time in 2011 and Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inducting it into their list of 500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll. In 2001, Eminem delivered a controlled performance of it live with Elton John at the 2001 Grammys, with Elton singing Dido’s parts, doing away with most of the pageantry and schtick of his usual live appearances.

Now a largely positive term claimed by hardcore appreciators of everything from Beyoncé to burritos, “Stan” plunges its hands into the messy dynamic between artists and their fans. In the beginning, Stan is presented as a highly relatable – typical, even. Who among us has not spent hours on end poring over the back catalogue of an artist whose music we fell in love with, covered our walls in their pictures and copied their hairstyle or dress sense? That’s literally half the audience at any given Paramore gig. The gradual build and eventual snap of Stan’s mental state, the detail about his life and first-person perspective humanise him in a way we come to hate and fear, but also pity. It adds shading to parts that are often left blank when stories like this get splashed across newspapers in real life.

With the resulting double homicide based on a narrative Eminem conjured up for himself two years prior, Stan is both a worst case scenario and a stereotypical example of male violence. He’s a dark hyperextension of fandom, but not unrealistic as a human being. Eminem is a carefully constructed and easily identifiable container for offence – we’re not supposed to see ourselves in him, but we are encouraged to see at least a little bit of ourselves in Stan.

More

From VICE

-

Andreas Rentz/TAS24/Getty Images/TAS Rights Management -

Helle Arensbak/Ritzau Scanpix/AFP/Getty Images -

Mark Weiss/Getty Images