The atmosphere in the new tuna-rearing facility in the small coastal town of Mazzaron, in southeastern Spain, is dead calm. It has to be. About 100 young Atlantic bluefin tuna, each about the size of a football, are adapting to life in a 22-by-10 meter tank. If spooked, they can burst straight into the wall, shattering their own spines.

Bluefin born in captivity die this way by the millions in their larval stage, but collisions grow less common as they age. Still, on the morning I visit the massive bluefin tanks at the Centro Oceanografico de Murcia, this is exactly what has happened to a one-year-old juvenile: face-first into concrete, dead on impact. “This is the first one to die in three months,” Dr Fernando de la Gandara, the center’s director, reassures me in a hushed tone.

Videos by VICE

The remaining juveniles perform an endless rapid loop of the tank, prowling the perimeter of their home with the same strong, efficient stroke that might otherwise propel them to Norway and back every year. Three other tanks nearby stand empty for the time being, awaiting future generations of domesticated bluefin.

Since 2003, the Spanish Institute of Oceanography (IEO), which operates the Murcia center, has been trying to domesticate Atlantic bluefin tuna, one of the ocean’s most powerful and coveted fish. By raising bluefin through its full lifecycle, the IEO aims to pave the way for commercial production, from tiny egg to giant apex predator to succulent slivers of sashimi.

So far, the IEO’s endeavor to tame bluefin has yielded slow progress and many setbacks. Bluefin tuna are exceptional hunters and don’t submit readily to aquaculture. Adults can grow as big as a cow, dive a mile below the surface to feed, and travel thousands of miles every year. They live up to 40 years and are phenomenal swimmers; their hydrodynamic shape inspires naval engineers. In a burst, they can accelerate past 40 mph, quicker than a sports car—a potentially fatal trait in a confined space. Deadly collisions are just one of the challenges of farming bluefin, but for the IEO’s partners and investors, the potential payoff more than justifies the effort and expense.

Prized for its buttery meat, bluefin commands outsized prices at market, especially in Japan, where 80 percent of tuna caught in the Mediterranean finish their journey as sushi. Bluefin’s popularity on the plate has nearly brought it to the brink of extinction. Since shortly after World War II, industrialized fishing has reduced the Pacific bluefin population to just 3 percent of unfished levels before the 1950s. Southern bluefin are also severely depleted, down to 13 percent of their unfished levels. The current state of Atlantic bluefin tuna is contested, but the International Union of the Conservation of Nature continues to list them as endangered.

Proponents of bluefin aquaculture want to protect wild tuna from overfishing and still meet our ravenous demand by controlling the supply, rather than simply trying to manage fisheries and curb consumer appetite. There would be no quotas for farmed bluefin from hatcheries, just delicious, all-you-can-eat fish—forever.

“That is why institutions like the European Union fuel our research to obtain bluefin tuna from eggs,” explains Dr Gandara. “Because there aren’t enough tuna in the sea to satisfy the market.”

“Ranching,” a much simpler version of tuna farming, has existed in the Mediterranean and elsewhere since the mid-90s. Unlike the IEO’s domesticated bluefin, ranched bluefin are caught wild and then fattened in ocean pens for two to ten months. At slaughter, they’re typically shot in the head by divers using explosive-tipped spear guns—the no-stress method—to preserve the meat. Bluefin hatcheries improve on ranching because they don’t deplete the threatened wild stock.

Ranching and farming bluefin tuna are costly endeavours, but the incredible demand, mostly originating in Japan, has lifted prices to roughly $25 USD per kilogram of gutted fish. “Our effort to obtain full-cycle bluefin tuna production is based in the international market,” says Dr Gandara. “The Japanese pay a fortune for the tuna. This high price maintains the expensive activity of fattening.”

Because Japan consumes so much tuna, the push to take control of “production” (i.e. the lifecycle) started there first, with Pacific bluefin. Japanese researchers are way ahead of their Spanish colleagues when it comes to breeding bluefin tuna, albeit a different species with different requirements. Scientists at Kindai University closed the lifecycle in 2002 of Pacific bluefin, and Japanese companies are now moving into full-scale production of Pacific bluefin raised from eggs.

Closing the lifecycle is a key milestone in aquaculture, one that the IEO achieved in July 2016—after 13 years of trying. This means that eggs were obtained from bluefin born in captivity; in other words, a captured tuna had grandchildren, and they didn’t die. However, most of those were lost six months later when a large storm destroyed their cage that winter. Now the IEO is raising domesticated bluefin to adulthood indoors at the new center, which opened in 2015.

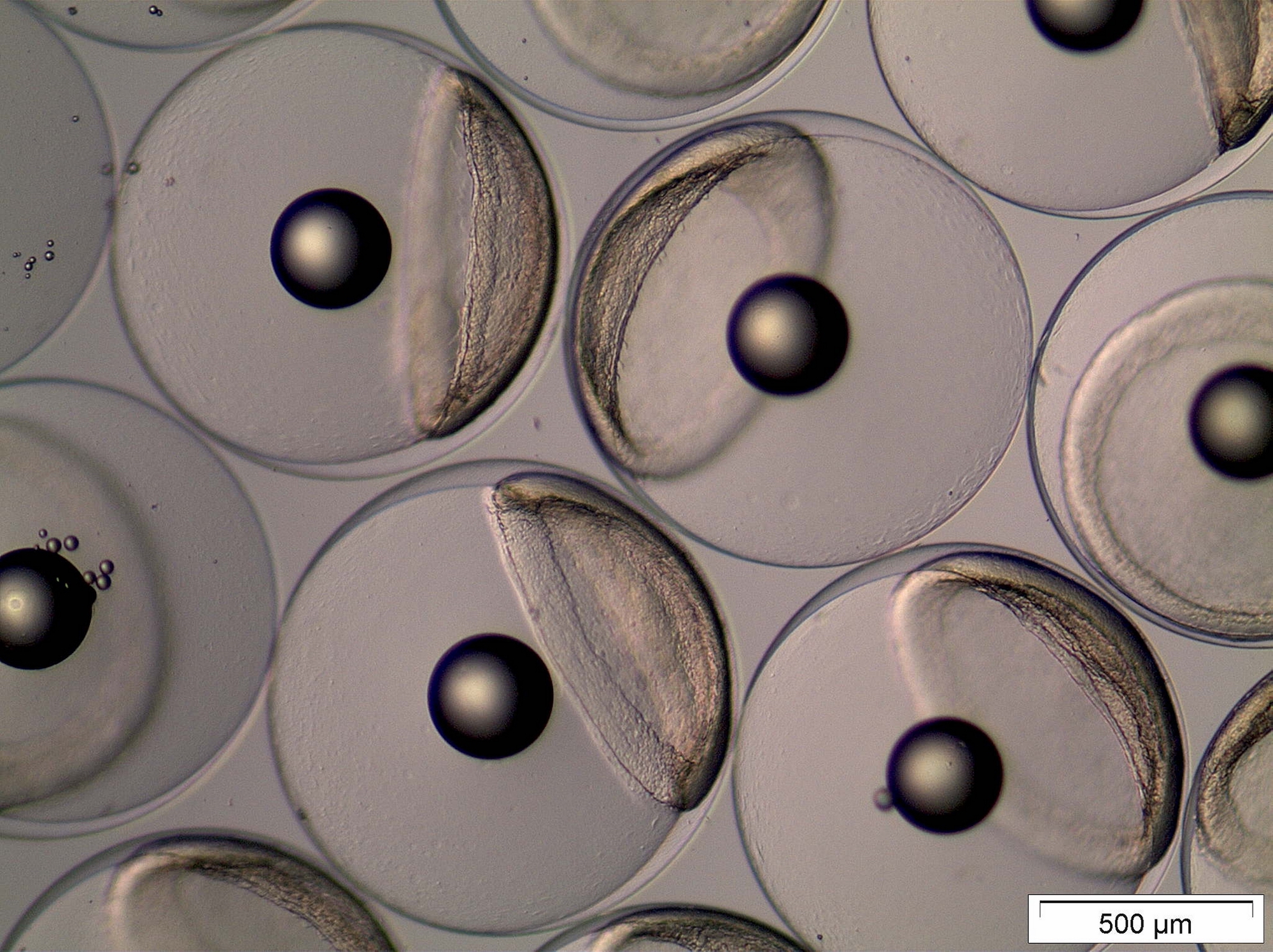

It’s not easy, as the mortality rate demonstrates. Presently, only 0.5 to 1 percent of Atlantic bluefin born in captivity and reared at the Murcia center survive past the larval stage—much fewer than other domesticated fish such as salmon, but dramatically more than survive in the wild. A single breeder bluefin can produce millions of eggs in one spawning season. Out in the Mediterranean, most of those will be eaten by their siblings.

Cannibalism is a big problem for baby bluefin. In the weeks following spawning season in late May, the researchers at IEO meticulously hand-separate them by size, so the bigger ones don’t devour the smaller ones. It’s sensitive work; because larval bluefin don’t have skin yet, they die when touched. Researchers must use small glasses and delicate nets to separate them.

The Murcia center’s main facility is essentially a farm for growing food for baby bluefin. Older bluefin eat baitfish like herring and mackerel, but larval bluefin feed on zooplankton, which the IEO scientists grow themselves, along with vats of colourful algae to feed the zooplankton. As the bluefin grow into fingerlings, they eat the larva of other fish, also raised on site. It takes three years for Atlantic bluefin to reach their minimum commercial weight of 40 kilograms.

The World Wildlife Foundation, Ocean Wise, and Monterey Bay Aquarium’s SeaChoice program all oppose eating bluefin—whether ranched or farmed—because of the amount of other small fish needed to feed them. In some cases, it can take as many as 40 kilograms of baitfish such as herring and mackerel to produce one kilogram of bluefin tuna. Baitfish populations worldwide are under intense pressure from the requirements of aquaculture. In his 2016 documentary Bluefin, John Hopkins reports that tuna and other large species off the shores of Atlantic Canada appear to be starving as a result of baitfish depletion.

To fix bluefin’s imbalanced Fish In Fish Out (FIFO) ratio, the IEO plans to develop a special mix that incorporates vegetable products with baitfish. Eventually, they say, they can get the ratio down below what it is in the wild. Researchers in Mexico have already used vegetable-and-fish diets to raise Pacific bluefin on a feed-conversion ratio of four kilograms to one.

That may not matter to connoisseurs, who know that the taste of bluefin depends on what it eats. During the spawning season in May and June, when wild Atlantic tuna swarm into the Mediterranean, Chef Paco Garcia serves bluefin exclusively at his upscale Madrid restaurant Ponzano. Garcia won’t buy farmed bluefin, he tells me, as we split a large bluefin steak worth 60 euros. “I prefer the wild ones,” he says. “The food they eat is better.”

The slab of wild tuna between us is lightly seared and deep purple inside. It lies on the plate like a lung. The flesh is thick and opulent, while the flavor is light and subtle. I can’t taste anything that would merit wanton overfishing, but all the same, I liked it OK.

More

From VICE

-

-

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

Collage by VICE -

Collage by VICE