Marine species that are normally found close to shore have been surviving for years in the open ocean on rafts made of plastic waste, reports a new study. The discovery exposes novel ecosystems that are now emerging due to widespread human pollution.

A surprising variety of coastal animals—including mollusks, anemones, and crustaceans—were found living, and even reproducing, on floating plastic debris in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, an ocean gyre between Hawaii and California that contains an estimated 80,000 tons of accumulated trash, according to the new research.

Videos by VICE

Whereas natural rafts made of wood or pumice rapidly biodegrade as they drift across oceans, plastic debris is extremely resilient, providing unprecedented access to the open open, known as the “pelagic” zone, to species that have never colonized it before.

Plastic pollution is a major problem in every environment on Earth, but it is particularly pernicious in our planet’s oceans. At least 11 million tons of plastic is dumped into the sea each year, and that number is expected to significantly increase in the coming years. As a consequence, tiny particles of plastic have reached every corner of the marine biosphere, including remote areas like the deep seas and the Arctic Ocean, a trend that is wreaking havoc on ecosystems that humans depend on for food and livelihoods.

Now, scientists led by Linsey Haram, a marine ecologist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, have identified 484 invertebrate species living on plastic debris collected from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which stretches across an area twice the size of Texas. An astonishing 80 percent of those species are typically found in coastal habitats, suggesting that “coastal species persist now in the open ocean as a substantial component of a neopelagic community sustained by the vast and expanding sea of plastic debris,” according to a study published on Monday in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

“Our results demonstrate that the oceanic environment and floating plastic habitat are clearly hospitable to coastal species,” Haram and her colleagues said in the study. “Coastal species with an array of life history traits can survive, reproduce, and have complex population and community structures in the open ocean.”

“The plastisphere may now provide extraordinary new opportunities for coastal species to expand populations into the open ocean and become a permanent part of the pelagic community, fundamentally altering the oceanic communities and ecosystem processes in this environment with potential implications for shifts in species dispersal and biogeography at broad spatial scales,” they added.

Prior to the influx of anthropogenic pollution, Earth’s oceans have typically presented a major barrier to species looking to colonize new territories. While some animals have managed to float across the open ocean on driftwood or volcanic debris, Haram and her colleagues note that this is typically a “high-risk, low-probability endeavor” because these natural materials can easily sink, get eaten by marine organisms, land in inhospitable environments, or end up permanently trapped in the open ocean due to currents.

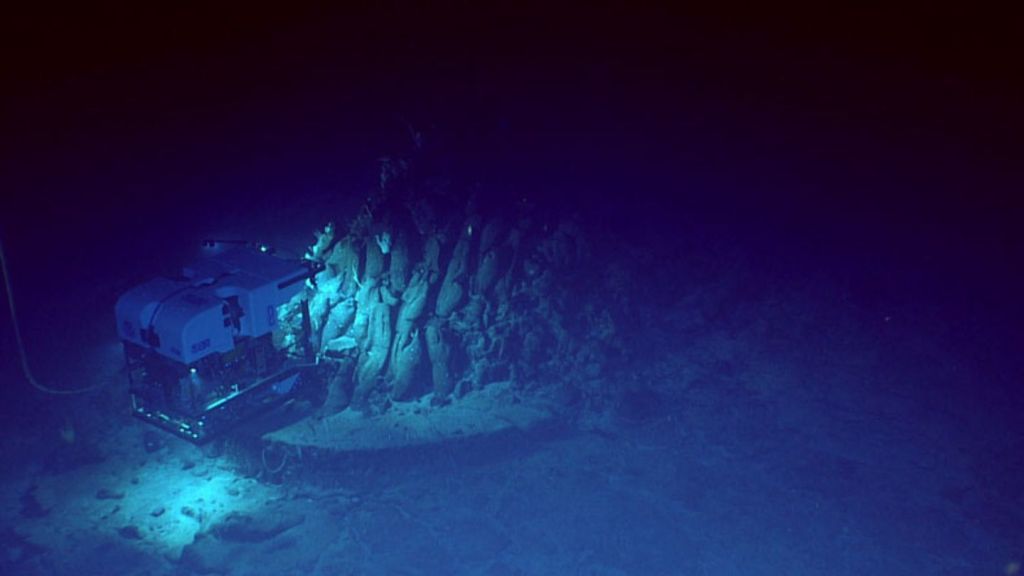

In order to investigate how plastic pollution may have changed the odds of survival in the open ocean, Haram’s team collected 105 items of floating plastic debris—such as ropes, nets, bottles, and other fragments—from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch between November 2018 and January 2019.

The team identified a wide variety of coastal invertebrates living on this waste, such as crustaceans, mollusks, and anemones that mostly originated from the Northwest Pacific. Species from coastal Japan were particularly common, likely due to the massive earthquake and tsunami that the nation experienced in 2011, which swept a large amount of anthropogenic waste into this polluted gyre.

The results line up with informal observations that have been collected in recent years. For instance, the long-distance swimmer Ben Lecomte spent months swimming through the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, where he witnessed an abundance of lifeforms thriving in the refuse.

Haram and her colleagues also discovered evidence of both sexual and asexual reproduction in many of these invertebrate populations, suggesting that the ecosystems can potentially survive for long periods in the open ocean on their plastic lifeboats. The findings hint that the coastal interlopers could become a permanent presence in these new environments, bringing them into direct competition with native pelagic species, though it will take more research to pinpoint the broader impacts of these plastic ecosystems.

“Our results suggest that the historical lack of available substrate limited the colonization of the open ocean by coastal species, rather than physiological or ecological constraints as previously assumed,” the researchers said.

“With plastic pollution waste generation and inputs to the ocean expected to exponentially increase over the next few decades, a steady source of substrate may sustain the neopelagic as a persistent community,” they concluded. “This research presents the cusp of discovery of neopelagic communities, and further innovative and interdisciplinary studies (including of trophodynamics and potential competitive interactions between pelagic and coastal species) are needed to more fully understand the role of floating plastics in ocean gyres.”