For decades Wang Shujun was known among Chinese activists in America as a dedicated champion of their cause. The unassuming dissident co-founded a group advocating democracy in China, where he rubbed shoulders with some of the best-known political exiles of his generation.

But to their shock earlier this year, the 73-year-old was accused of being an informer for Beijing.

Videos by VICE

Arrested by U.S. authorities in March, Wang was charged with espionage in a federal court in Brooklyn last week, along with four Chinese intelligence officers who allegedly acted as his handlers. A criminal complaint filed by U.S. prosecutors detailed how China’s secret police ostensibly planted a snitch in the inner circles of Chinese dissidents.

“There have always been people posing as activists but are in fact collecting information for the Chinese government,” said Teng Biao, a human rights lawyer and legal scholar, who was repeatedly detained in China for his work and fled to the U.S. in 2014. “But the news left many activists flabbergasted, because no one ever suspected him.”

Wang first set foot in the U.S. in the 1990s as a visiting scholar at Columbia University in New York, where he received a special talent visa for outstanding professors and eventually became a naturalized American citizen in 2003. Three years later, he founded the Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang Memorial Foundation, in honor of the ousted Chinese leaders who favored liberal reforms.

The death of Hu, who led the Communist Party toward economic and political liberalization, in April 1989 precipitated protests in Beijing that ended in the Tiananmen Square massacre, prompting a political exodus. Wang, a social science professor at the time, was among those who left the country.

Hu Ping, a veteran democracy campaigner who served on the board of the foundation, remembered Wang as a cordial administrator who always wore a smile on his face. “He helped organize events and would ring up each member one by one and notify them before each meeting,” Hu told VICE World News. “He got along with everyone.”

But Wang’s enthusiasm might have been a facade. The FBI found that Wang had used his position and status within the Chinese diaspora communities to covertly collect information on prominent activists and human rights leaders since at least 2011. The four Chinese agents, who remain at large, directed him to snitch on individuals and groups that China considers subversive, including pro-democracy activists from Hong Kong, advocates for Taiwanese independence, and Uyghur and Tibetan activists. VICE World News could not reach Wang or his legal representatives for comment.

Based on a filing by the FBI, Wang carried out the spying discreetly and methodically. To reduce his digital footprint and avoid detection, Wang communicated with his handlers through encrypted channels, saving their contacts in a black, physical address book, instead of his phone. He detailed private conversations he had with other dissidents and their activities in “diaries,” which were saved as drafts in an email account the Chinese agents could access from China.

In one entry in March of 2019, Wang listed possible speakers and attendees at a protest in New York that commemorated the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, highlighting a speaker who was expected to deliver an hour-long speech “without any reservations.” He also reported a possible attempt by a protester to block Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s car when he visited former President Donald Trump at Mar-a-Lago. The trip was eventually canceled. U.S. authorities found more than 160 such entries at Wang’s residence.

Another prime target of Wang was said to be Albert Ho, former chairman of the Democratic Party in Hong Kong. To cozy up to the former opposition lawmaker, Wang spent more than $4,000 treating him and his family to dinner and offered to host him in New York when he visits. After a phone conversation with Ho in 2016, Wang immediately reported to an officer at the Guangdong State Security Bureau named Little Li, saying he received “candid” answers to “necessary questions.” “Great,” Little Li replied with a thumbs-up emoji, instructing Wang to write it in a “diary.”

As the investigation found, Wang’s surveillance of Ho was only part of “a multifaceted effort” by the Chinese government to track Ho, who is now behind bars in Hong Kong for a separate case related to charges of unlawful assemblies.

Wang’s alleged double life finally came to light last year. Playing Wang at his own game, an undercover law enforcement agent visited him at his apartment in Norwich, Connecticut, posing as a messenger from one of his handlers, Boss He. Claiming Wang’s electronic communications might be monitored by the FBI, the agent offered to cover his tracks and tricked Wang into handing over his electronic devices and the passwords of the email account.

“If anyone doubts how serious the Chinese government is about silencing its critics, this case should eliminate any uncertainty,” said Alan E. Kohler Jr. of the FBI’s national security branch, noting that the Chinese government’s aggressive tactics are no longer confined to its borders.

The Chinese embassy in Washington has denied the spying accusations, calling them “pure fabrication,” according to a statement to Reuters.

In hindsight, Hu, the democracy campaigner, recalled that Wang frequently shared books he wrote and published in China about the history of the Pacific War. It struck Hu as odd that Wang, a critic of Beijing, traveled frequently to China and was warmly received there, but he brushed it off at the time. Hu speculated that it was during one of these visits when Wang was co-opted by Chinese security officers.

“The Chinese Communist Party is constantly seeking to recruit informers. Dissidents who return to the country would be approached by relevant departments and asked to cooperate and collect intelligence,” Hu said. “Some do and some don’t.”

Deng Yuwen, a political commentator who is the secretary-general of the foundation Wang co-founded, said some associates noticed something was off with Wang well before his arrest.

“His methods are too clumsy,” Deng told VICE World News. “He appeared too eager, taking pictures at occasions where photos aren’t called for. Some activists, who were more cautious, took pains to avoid events where he would be present.”

The U.S. authorities might have acted on tip-offs, he added.

As much as I hate spies, I am against making unfounded accusations because it is almost impossible for ordinary people to identify them.

Despite the revelation, most activists have long been familiar with the tactics of China’s United Front Work department, which seeks to neutralize and co-opt perceived threats to the Chinese Communist Party, and were therefore not alarmed. “Since we began the foundation, we knew there would be an infiltrator among us,” Hu said. “But the damage he can do is limited, because most of our activities and remarks are public in the first place.”

Wang is neither the first informer, nor would he be the last, Deng said. But with U.S. authorities now keeping a close eye, it will be increasingly difficult for China’s intelligence officers to operate under their nose, he added.

Despite knowing how extensive China’s surveillance network is, Teng, the legal scholar, cautioned against rash attempts to root out spies. “As much as I hate spies, I am against making unfounded accusations because it is almost impossible for ordinary people to identify them,” Teng said. “Pointing fingers might harm the innocent and would only sow distrust in the community.”

But like many other dissidents, Teng saw the disclosure of the investigation as a positive sign that Washington is taking these surreptitious activities seriously. “It is a warning from the U.S. administration to the Chinese government that we are investigating these incidents and we will not sit on our hands and do nothing.”

Follow Rachel Cheung on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

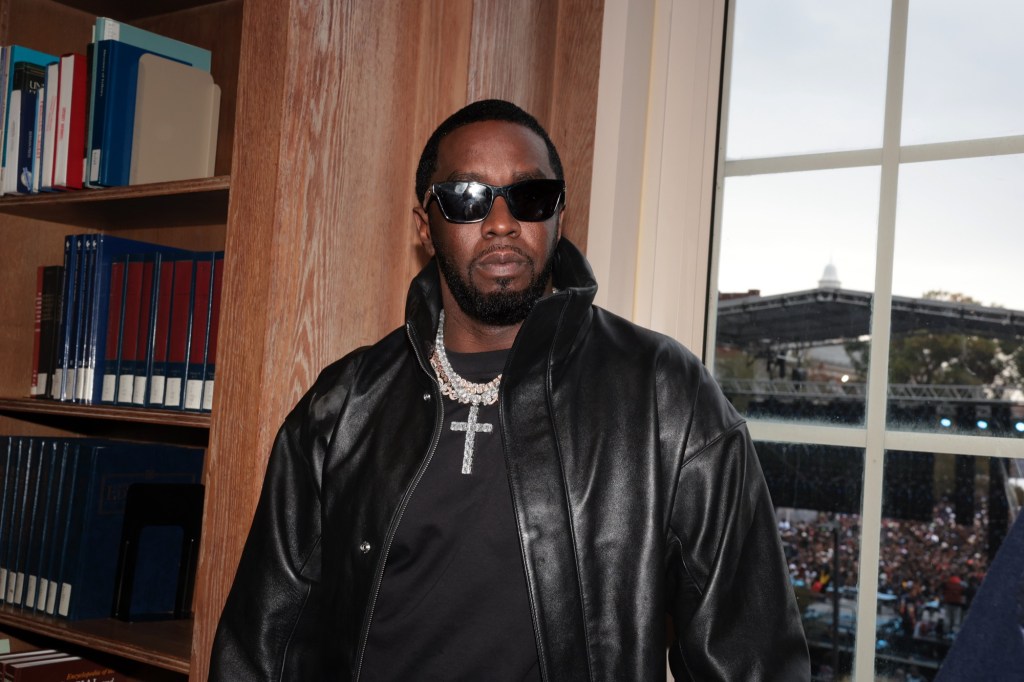

(Photo by Shareif Ziyadat/Getty Images for Sean "Diddy" Combs) -

Jake Burghart -

Sean Combs in 2012. Photo by Hahn-Marechal-Nebinger/ABACA/Shutterstock. -

Shutterstock for Consensus