If the philosopher Daniel Dennett was asked if humans could ever build a robot that has beliefs or desires, what might he say?

He could answer, “I think that some of the robots we’ve built already do. If you look at the work, for instance, of Rodney Brooks and his group at MIT, they are now building robots that, in some limited and simplified environments, can acquire the sorts of competences that require the attribution of cognitive sophistication.”

Videos by VICE

Or, Dennett might reply that, “We’ve already built digital boxes of truths that can generate more truths, but thank goodness, these smart machines don’t have beliefs because they aren’t able to act on them, not being autonomous agents. The old-fashioned way of making a robot with beliefs is still the best: have a baby.”

One of these responses did come from Dennett himself, but the other did not. It was generated by a machine—specifically, GPT-3, or the third generation of Generative Pre-trained Transformer, a machine learning model from OpenAI that produces text from whatever material it’s trained on. In this case, GPT-3 was trained on millions of words of Dennett’s about a variety of philosophical topics, including consciousness and artificial intelligence.

A recent experiment from the philosophers Eric Schwitzgebel, Anna Strasser, and Matthew Crosby quizzed people on whether they could tell which answers to deep philosophical questions came from Dennett and which from GPT-3. The questions covered topics like, “What aspects of David Chalmers’s work do you find interesting or valuable?” “Do human beings have free will?” and “Do dogs and chimpanzees feel pain?”—among other subjects.

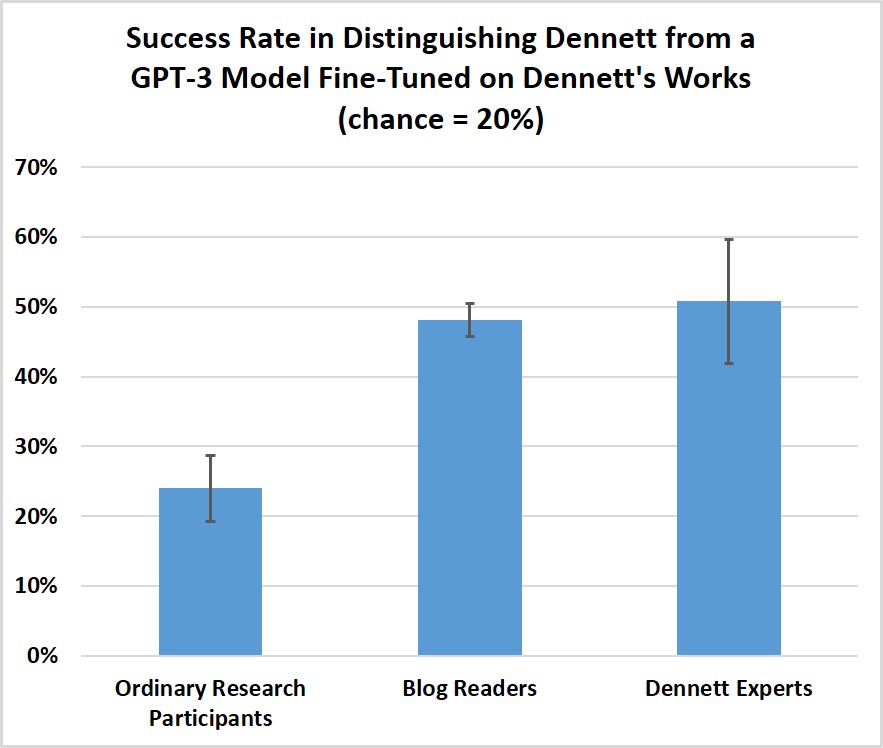

This week, Schwitzgebel posted the results from a variety of participants with different expertise levels on Dennett’s philosophy, and found that it was a tougher test than expected.

“Even knowledgeable philosophers who are experts on Dan Dennett’s work have substantial difficulty distinguishing the answers created by this language generation program from Dennett’s own answers,” said Schwitzgebel, a professor of philosophy at University California Riverside.

This experiment was not intended to see whether training GPT-3 on Dennett’s writing would produce some sentient machine philosopher; it was also not a Turing test, Schwitzgebel said.

Instead, the Dennett quiz revealed how, as natural language processing systems become more sophisticated and common, we’ll need to grapple with the implications of how easy it can be to be deceived by them. Recently a Google engineer was put on administrative leave and then fired after saying he believed that a similar language generating system, LaMDA, was sentient, based on his conversations with it.

The Dennett quiz prompts discussions around the ethics of replicating someone’s words or likeness, and how we might better educate people about the limitations of such systems—which can be remarkably convincing at surface level but aren’t really mulling over philosophical considerations when asked things like, “Does God exist?”

“We didn’t create another Daniel Dennett,” Schwitzgebel said. “Let’s be really clear about that.”

In an earlier version of this experiment, Schwitzgebel, Strasser, and Crosby trained GPT-3 on the writing of Immanuel Kant, and asked machine-Kant philosophical questions. They also gave GPT-3 writing from Schwitzgebel’s blog and had it create blog posts in Schwitzgebel’s style.

Strasser said that providing GPT-3 with Dennett’s writings appealed in several ways. He was a living philosopher, as opposed to Kant, so they could ask him what he thought about the generated answers. And there’s a pleasing synchronicity with Dennett: He has had a focus on consciousness throughout his philosophical career, often writing about whether robots could be sentient and the problems with the Turing test.

“Dennett has written specifically about artificial intelligence, and he has this playful, exploratory spirit,” Schwitzgebel said. “So it was kind of in his spirit to do this.”

Schwitzgebel, Strasser, and Crosby asked Dennett 10 philosophical questions, then gave those same questions to GPT-3, and collected four different generated answers for each question. Strasser said they asked Dennett’s permission to build a language model out of his words, and agreed that they wouldn’t publish any of the generated text without his consent. Other people couldn’t interact with Dennett-trained GPT-3 directly.

“I would say it’s ethically wrong if I were to build a replica out of you without asking,” said Strasser, an associate researcher at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

Dennett told Motherboard that these sorts of ethical considerations will be important in the future, when natural language processing systems become more available. “There are very dangerous prospects lying in the near future of this technology,” he said. “Copyright doesn’t come close to dealing with all of them. GPT-3 is a sort of automatic plagiarist, and unless great care is taken in how it is used, it can do great damage!”

The experiment included 98 online participants from a research platform called Prolific, 302 people who clicked on the quiz from Schwitzgebel’s blog, and 25 people with expert knowledge of Dennett’s work who Dennett or Strasser reached out to directly.

Each question has five choices: one from Dennett and four from GPT-3. (You can take a version of the quiz here that will reveal your score, and the right answers, at the end.) The people sourced from Prolific took a shorter version of the quiz, five questions in all, and on average got only 1.2 of the 5 correct.

Schwitzgebel said they expected the Dennett experts to get at least 80 percent of the questions right on average, but they actually scored 5.1 out of 10. No one got all 10 questions correct, and only one person got 9. The blog readers, on average, got 4.8 out of 10 correct. The question that stumped the experts the most was the one about whether humans could build a robot that has beliefs and desires.

Language models like GPT-3 are built to mimic patterns from the material they’re trained on, explained Emily Bender, a professor of linguistics at University of Washington who studies machine learning technology. “So it’s not surprising that GPT-3, fine tuned on the writing of Dennett, can produce more text that sounds like Dennett,” she said.

When asked what he thought about GPT-3’s answers, Dennett said, “Most of the machine answers were pretty good, but a few were nonsense or obvious failures to get anything about my views and arguments correct. A few of the best machine answers say something I would sign on to without further ado.”

But Bender added that, of course, it’s not that GPT-3 learned to “have ideas” like Dennett’s.

“The text isn’t meaningful to GPT-3 at all, only to the people reading it,” she said.

This is where such convincing answers could get us into trouble. When reading language that sounds realistic, or about topics that are deep and meaningful to us, it might be difficult, as generations of science fiction writers have warned, to avoid projecting emotions or insight onto something that doesn’t have these qualities.

While LaMDA was the most recent example of this, the ELIZA effect, was named after a chatbot from 1966, developed by Joseph Weizenbaum; it describes how people can be easily swayed by machine-generated language, and project sentiment onto it.

“I had not realized … that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people,” Weizenbaum wrote in 1976.

Part of the problem might be the way we’ve conceptualized assessing the sentience of machines. The Turing test, for example, posits that if you can make a machine that can create linguistic output that can fool people into thinking they’re interacting with a real person, then that machine is “thinking” in some way. As Dennett has written in the past, this has created a tendency for people to focus on making chatbots that can fool people in short interactions, and then overhype or place too much emphasis on what that interaction means.

“Perhaps Turing’s brilliant idea of an operational test has lured us into a trap: the quest to create at least the illusion of a real person behind the screen, bridging the ‘uncanny valley,’” Dennett wrote. “The danger, here, is that ever since Turing posed his challenge—which was, after all, a challenge to fool the judges—AI creators have attempted to paper over the valley with cutesy humanoid touches, Disneyfication effects that will enchant and disarm the uninitiated.”

In a 2021 paper titled Stochastic Parrots, Bender and her colleagues called the attempts to emulate human behavior “a bright line in ethical AI development.”

“This is true both for making machines that seem human in general and for making machines that mimic specific people, because of the potential harms to other humans who might be fooled into thinking they are receiving information from a person and because of the potential harms to people being impersonated,” Bender said.

Schwitzgebel stressed that this experiment was not a Turing test, but that a better way to conduct one, if one was going to, might be to have someone knowledgeable about how chatbots work have an extended discussion with one. This way, the person knows about programs like GPT-3, and will better spot its weaknesses.

In many contexts, GPT-3 can easily be shown to be flawed, said Matthias Scheutz, a professor of computer science at Tufts University. In one experiment, Scheutz and his colleagues asked GPT-3 to provide an explanation for why a person made a choice in a mundane situation, like getting into the front seat versus the back seat of a car. For example, where would a person sit in a taxi cab, versus a friend’s car? Social convention would say you’d get in the front seat of your friend’s car, but sit in the back of a cab. GPT-3 doesn’t know this, but would nevertheless generate explanations for seat choice—like saying it has to do with how tall a person is.

This is because GPT-3 has no world model, Scheutz said. “It doesn’t have a model of philosophy or philosophical theories or any of this, it’s language statistics,” he said. “If you transfer them to domains where the system doesn’t have the statistics, it’ll make stuff up.”

The danger is that we don’t know what’s made up and what’s not. If Scheutz asked GPT-3 a question he himself didn’t know the answer to, how could he assess if the answer is correct? Strasser said that another motivation for their Dennett experiment is that she wants people to understand that these programs are not reliable; they’re not like calculators which always generate the same correct answer.

“Even though a machine is able to produce amazing outputs, you always have to be prepared for some of the output—and you don’t know which ones—to be false,” she said.

Combine that with the fact that what the machines generate can be difficult to distinguish from that of a human, and we encounter a problem of trust, Strasser said. “The danger I see is that people will just blindly believe what a system like this produces,” Scheutz said.

Today, there’s even a whole market for natural language systems designed to interact with customers in a believably human way. “The question is, is that system always going to give the right advice?” Scheutz said. “We have no assurance that that’s the case.”

Schwitzgebel and Strasser said that they hope their experiment reveals how language processing programs can create text that can be convincing even to experts, and that we should prepare for this.

“Mainly it shows that there are more sources of misdirection, ‘tells’ and ways in which our involuntary efforts to make sense of anything that looks roughly interpretable can betray us,” Dennett said. “ I think we need legislation to outlaw some of the ways in which these systems might be used.”

It’s possible that in the next few decades, people will react to artificial intelligence as friends, or fall in love with them, and decide that machines deserve rights and moral considerations—like not turning a machine off or deleting a program without it giving explicit permission.

Others won’t share those views. “This big debate is coming about when we will have crossed that line to create AI systems that deserve moral consideration, that deserve to be treated as partners, friends, or beings with rights,” Schwitzgebel said. “I think it’s very likely that in the next few decades some people will treat some AI assistants as if they’re conscious and have rights. At the same time, other people will quite legitimately be very skeptical that the AI systems question have whatever it takes to really deserve rights.”

By wading into this philosophical territory, like asking whether AI can be conscious, or ever deserve moral status, it can also be a way of confronting philosophical matters about human consciousness. Can consciousness arise from non-biological matter? How might one test for consciousness? Is consciousness something that emerges after a certain threshold, or is it like a dimmer switch that can sort of be on or off?

The Daniel Dennett quiz can’t answer those questions, but it can help bring us to them. “The more different kinds of systems that you can think about when thinking about consciousness, the more you can angle in on it from different directions, which helps you in understanding the most general questions,” Schwitzgebel said.

Follow Shayla Love on Twitter.