In 1979, Derek Boshier met David Bowie on a blind date.

Boshier, the British pop artist who first made his name in the swinging London scene of the 1960s, was at the time curating a photography exhibition at London’s Hayward Gallery, a major stronghold for contemporary art. The collection, Lives: An Exhibition Of Artists Whose Work Is Based On Other Peoples’ Lives, featured luminaries including David Bailey, David Hockney (with whom Boshier attended art school), and fashion and portrait photographer Brian Duffy. After the opening, Duffy called to say he had a friend he thought Boshier would get along with. He wanted them to meet.

Videos by VICE

“The way he framed it, I thought it was a female, and I thought it was a blind date,” Boshier recalls on a gray Wednesday afternoon at LA’s Night Gallery with a lilting Portsmouth accent. “So he told me to come to his studio. I arrived there, and it was David.”

The date-that-wasn’t sparked a 37-year friendship and professional relationship that began when Boshier designed the art for Bowie’s 1979 LP Lodger. The image, photographed by Duffy, who also shot the Aladdin Sane cover, depicts Bowie battered, disheveled, and tumbling clumsily. (Falling and the vulnerability therein are a longstanding theme of Boshier’s output, inspired by the work of 18th century English poet and visual artist William Blake.) Boshier’s design for the album’s inner gatefold featured a collage of found images including running water, an infant, wristwatches and the corpse of Che Guevera, altogether representing the themes of life and death explored on Lodger. He also designed the art for 1984’s Let’s Dance , which depicted Bowie in boxing gloves with Boshier’s 1980 work A Darker Side of Houston projected on his bare chest. When commissioning Boshier to design stage sets for his Serious Moonlight tour, Bowie advised the artist to, “think big band; think punk” and avoid concerns regarding size and ease of installation. This is what resulted.

Bowie, a prolific art patron whose personal collection earned more than $41 million when it was auctioned off by Sotheby’s last year, amassed a hefty collection of Boshier’s drawings, maquettes and more throughout his lifetime. The two remained close until Bowie’s death in January 2016.

Bowie wasn’t Boshier’s only musical collaborator. The artist also designed album artwork for 60s English rock act The Pretty Things, played tennis with the band’s lead singer Phil May, and tutored a young Joe Strummer before collaborating with The Clash on 1979’s CLASH: 2nd Songbook, a collection of drawings and paintings released in conjunction with the group’s sophomore album Give ‘Em Enough Rope. While living in Texas in the 80s, Boshier immersed himself in gospel music and reggae, finding inspiration in each genre’s inherent racial issues.

Now 80, Boshier has lived and worked in LA for 17 years. A one-time Trotsky disclple who was involved in British politics during the 70s, he continues using his work to confront ideas surrounding government, revolution, war, sex, and popular culture with playful subversiveness and dark humor. (“I gave you a choice,” he says, gesturing to the halo and devil horns he once painted on an image of Bill Clinton.) His output during the last five decades has included paintings, drawings, dioramas, collages, videos and more – with his style defined by meditations on the duality of existence and an accessible approach mixing images and words, found items and traditional materials, and high and low culture. Often sourcing materials from thrift stores and tourist shops, he combines a keen awareness of pop culture — a recent piece is called “Paris France, Paris Texas, Paris Hilton” — with historical and religious themes. He will soon begin work on a Trump-related poster.

On The Road, a new exhibition at Los Angeles’ Night Gallery, features dioramas, collages, drawings, maquettes and paintings taken from throughout his career, along with three new large scale paintings featuring his one-time blind date, and another new series exploring our relationship with technology. This show, which moves to London in the fall, follows the nearly 100 solo and group exhibitions Boshier has been a part of in the United States and Europe since graduating from art school in 1962.

Despite the neck brace he wears due to a recent surgical procedure, Boshier is spry and funny as he gives a private tour of the Downtown Arts District gallery space, prolifically using the word “fuck” as he leads me from piece to piece.

“I did the fucking thing and then they told me they weren’t doing the project anymore, and I asked to have the art back, and they said they’d lost it,” he says, recalling his work with the Pretty Things. “Fuck ’em!”

Tall and reedy, Boshier clings to his iPad on which he shows me three recent films—one a music video he made for a rock song about himself that will be featured in an upcoming collection of tracks about fine artists including Basquiat, Ed Ruscha and Peter Blake, the cover art designer for Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. These songs are taken from the collection Robert Fraser’s Groovy Arts Club Band, a forthcoming musical homage to legendary 60s London art dealer Robert Fraser. Boshier puts on his song “An Englishman in LA” (sample lyrics: “jolly good is a long way from Hollywood!”), and nods his head as it plays. The other videos are video collages composed of drawings, photos and audio clips taken from news, radio, commercials and pop music. Boshier watches the screen closely during each, his blue eyes sparkling with a youthful enthusiasm that betrays his age.

We sat down with Boshier to reflect on Bowie, The Clash, and the fuckin’ internet.

Noisey: What was your reaction when you walked in the door that day and realized your blind date was with David Bowie?

Derek Boshier: You try not to go [ drops jaw]. You try to look cool! I got to know him very well. I designed stage sets for him after the Lodger album, for the Serious Moonlight tour. He didn’t use it actually, but he incorporated parts in other shows. I made a couple of portraits of him as the Elephant Man when he was in New York. David was my best collector. Over the years he bought a lot of my work.

But he had been a fan of your work before you met him, right?

I had been to an art book store in London, and someone said to me, “Do you know David Bowie?” and I said, “Well I know of him.” The person in the shop said, “Oh he’s just been in here asking if there were any books on you.” Then I got to know him—he came to my openings in Paris and stuff—and he was such a good guy, so generous and good to be with.

When was the last time you spoke with him before he passed?

About two and a half months before he died, he sent me an email to say how much he liked my [2015 monograph Rethink/re-entry] book. David is a musician and is also a great lyricist, and it’s only a very small thing [he did in the email], and it’s a thing that a lyricist would do: He said, “Derek, I’ve got to write to you to say how much I love your Rethink/re-entry book. Your work cascades down the decades.” Cascades down the decades! It’s just a little thing, just a little bit of poetics, and that’s what he was also good at. I thought, “I’ll wait a bit and then I’ll do a drawing and I’ll send it to him,” and then he died.

Did you know he was sick?

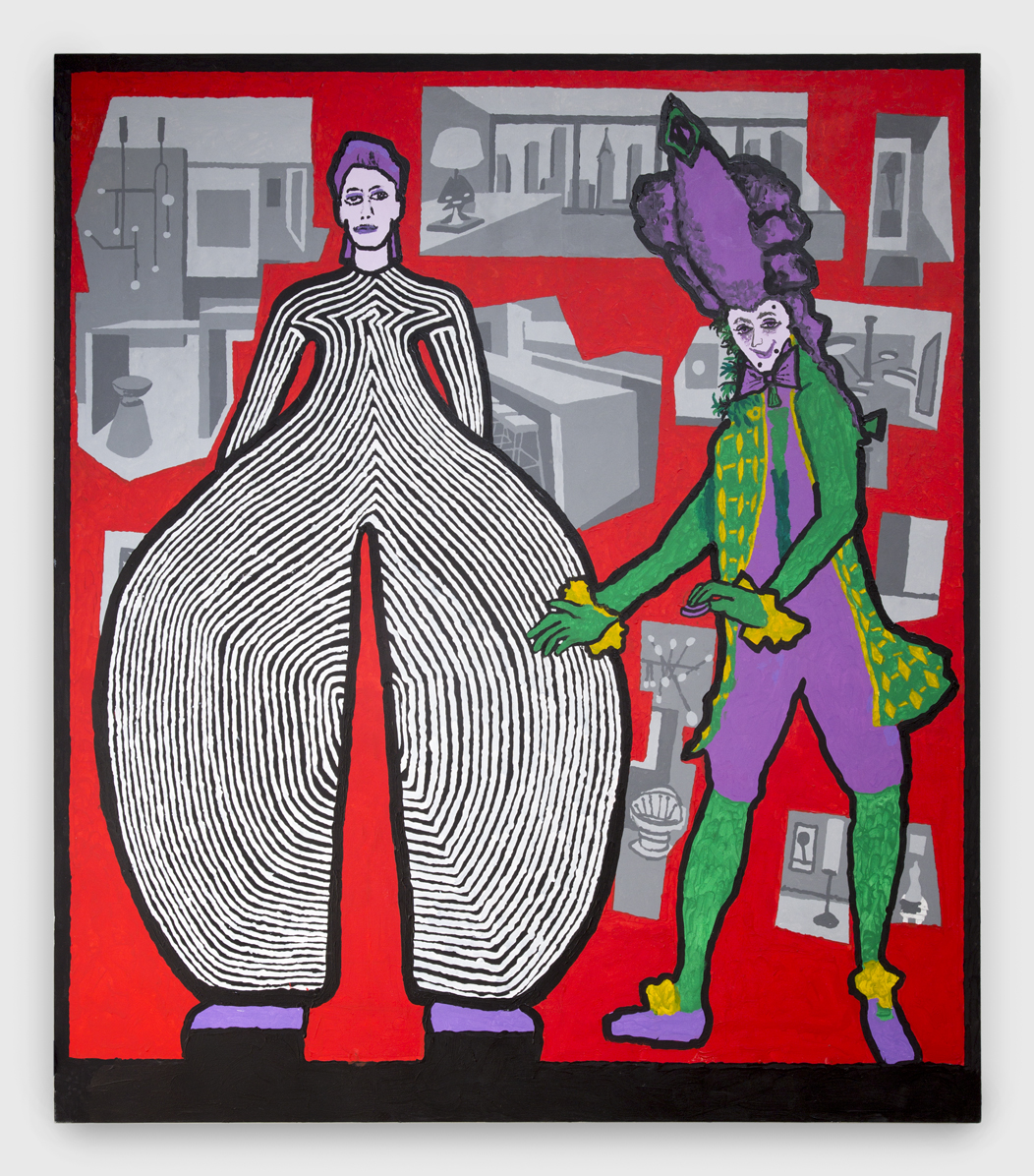

No. No one did. After, I had this idea of at least doing a painting for him. When I was thinking about doing a painting about David, I kept thinking, “What should I do?” I was in London, and there was a construction site and I came across a big notice saying, “This construction site was the site of one of the greatest nightclubs in the world, ever.” It was set up by Teresa Cornelys, who I think was the 18th century David Bowie. She was influencing fashion; she was influencing all sorts of events. She influenced music, although it was classical music. Everyone wanted to go to her parties. There were always red carpets to everything she went to, and hundreds of people just gawking at the celebrities who would walk through. So this piece is called “David Bowie and Theresa Cornelys.” David is wearing the Tokyo-pop costume designed for him for the Aladdin Sane tour.

And then you did this one next to it?

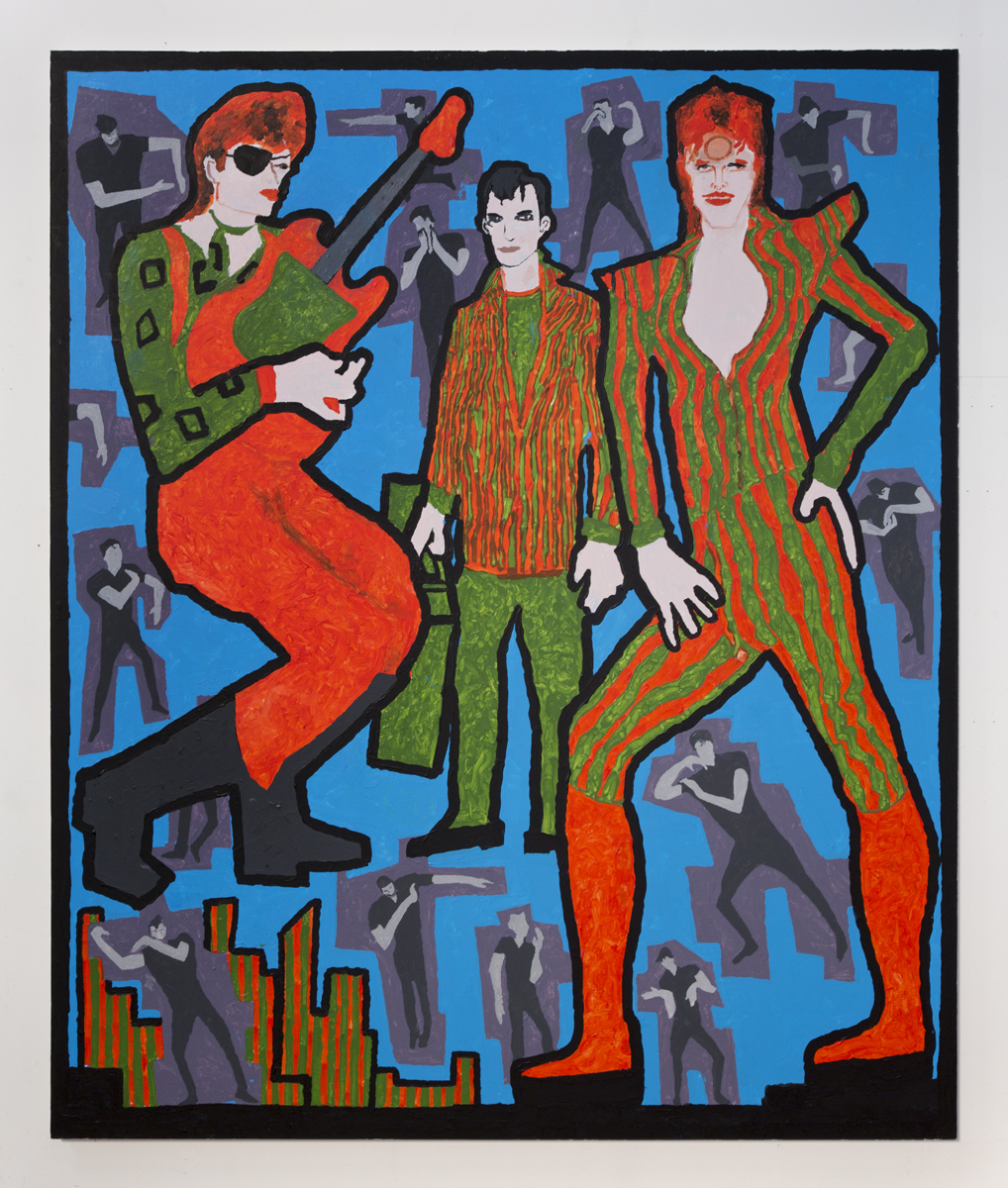

Then I did this second one, which is called “David Bowie, Twice.” I wanted this one to be like the other one, a continuation of the idea of contrasts. Of course that’s what David was. He had so many different personas. This is an image from his “Scary Monsters” video. I wanted to have one of the sharpest contrasts I could, which is what he wore when he used to hang about New York. This is his civilian clothing, as it were. You’ll notice in the pose that he’s pointing his finger down, to Iman.

Why is he doing that?

There’s a very famous picture by Goya in which he paints his mistress. He was criticized for depicting his mistress not in the finest formal dresses of the aristocracy, but one down, and that was thought of as terrible. In it, his mistress stands there with her finger pointing down, and at the bottom it says “Goya.”

What’s happening in this painting here? Is that Jack Kerouac?

I came across an interview by David that I hadn’t seen before, and in it he talks about how terribly unhappy he was during his school days. Not only at school, but also at home. He didn’t get on with his mother, never did all his life. His father had a drinking problem, however he did seem to patch it up with his father later. He said at school they forced him to write right-handedly, because he was left-handed.

But he said what changed his life was reading Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, so this painting is called “David Bowie, Jack Kerouac, and David Bowie.” He said, “I realized by reading it that I didn’t have to be conventional.” So he went out and he bought a saxophone and started painting. In the background is B-Boy dancing. It comes out of breakdancing and is now more sophisticated, more like ballet and mime. This image is taken from a film of my girlfriend’s youngest son.

How did you connect with The Clash?

Joe Strummer, I was one of his tutors during his first year at art school. He used to sit in class playing a wooden guitar and say, “Hey man, call me Woody, man.” The reason is because he, like Bob Dylan, was a huge fan of Woody Guthrie. So about three or four years passed, and they had become very famous as The Clash. I was walking down the street in London, and who should be coming towards me but Woody. But now Woody was all dressed in black with Doc Martens on and fans screaming by. I went up to him and said “Woody!” He said “I’m not called Woody now,” and I said, “I know you’re not, I’m just joking. I know all your songs. I’m a great fan.”

Did Strummer ask you to collaborate with them on their art?

A couple weeks later, I had a phone call from another ex-student called Caroline Coon. She said, “I hear you met Joe. I’ve just been in conversation with him and he wants to know if you would design Clash: Second Songbook.” To put that in perspective, MTV didn’t come into existence until 1981. This was two years before, so what all rock groups did at the time was songbooks. They had a thousand photographs and were fanzines basically, but very upmarket. I said, “Well what’s my brief?” Caroline said, “Well, it’s 48 pages. Here’s all of the lyrics. Do what you fucking like.” He was great, Joe. Pity he died so young.

There are several new pieces in the show that depict people holding up iPhones against incredible landscapes. Tell me more about these works.

This is a new series called “Otherwise Engaged.” My work always comes out of popular culture, always has. Whatever the popular culture phenomenon of the time, I make a painting. Now it’s like you’re at a dinner with someone and they’re pretending to listen to you and meanwhile they’re like [gestures like he’s looking at a phone under the table] and it’s like “Fuck you. You’re fuckin’ addicted.”

Technology is clearly very much on your mind.

Because it’s the way most people see the world. Everyone sees the world encased in black and white. We see the world in theater, cinema, iPhones, computers, and then there’s real life.

What’s your feeling on that, especially as someone whose career depends on receiving the attention of an audience?

I’m intrigued by it. Who would have thought when I was a kid that you would be able to walk around with a telephone. Telephones were stuck in one place, and now in your hand you can watch a movie. It’s amazing! And then there are bad points, and that’s to do with people getting so much of their information from the information age. It also kills the art of conversation. I went on Facebook for a few weeks. People were sending me things like, “Hi, I just seen a transsexual in a garage in Seattle.” I’m not fuckin’ interested!

That’s the thing about the internet, especially when you’re a public figure. Anyone can get to you.

I know! That’s why I came off it. I don’t want to talk to these fuckin’ people! I’ve got to protect myself. Now I have gone on Instagram, but I don’t answer ever. Someone else puts the photos up for me.

Katie Bain is talking to these fuckin’ people on Twitter .

More

From VICE

-

-

(Photo by Amy Sussman; JOSEPH PREZIOSO/AFP via Getty Images) -