A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

The tale of Ring, the startup that Amazon acquired recently, is a fascinating one: An idea that got rejected on Shark Tank under a different name, the concept quickly found steam from new investors like the rapper Nas and became one of the most interesting forms of home automation, an industry that, according to Statista, is worth a cool $18.9 billion in 2018.

Videos by VICE

But home automation had to start somewhere, and I’d like to argue that, barring any homes of the future, it really started gaining mainstream momentum with a device marketed by a guy perhaps better known for the Ch-ch-chia Pet.

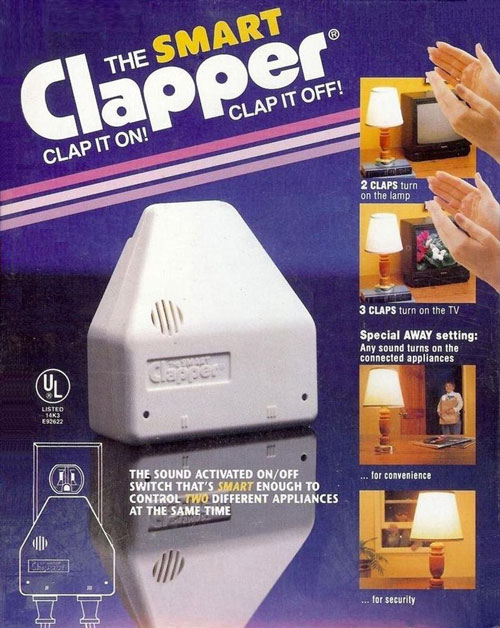

Admittedly, The Clapper didn’t even do all that much compared to modern home automation tools. It could turn on your coffee maker with a clap, but not much more. But its design and approach—to extend the function of a home through electronics, perhaps to even make it a little smarter—shares a lot of cues with the automation tools of the modern day. (A great example is Belkin’s Wemo line of smart plugs, which make it possible to control your outlets with a smartphone, for example.)

Here’s the story of the Clapper, which takes a hands-off approach to turning on the lights.

Why The Clapper was still an important invention for home automation, even if it wasn’t first

When it comes to home automation, there are definitely things that came before The Clapper—which only showed up during the late 1980s. So why should we care?

It comes down to a combination of promotion and disposability.

The X10 system, an earlier, more elaborate form of home automation that relied on remote controls and a power-line-based communication protocol, is more likely to earn the claim of being the first mainstream home automation technology. And while it did a lot more, it was very complex and not a good fit for every home—which is probably why the company was trying to sell webcams instead of automation systems to the mainstream consumer.

The Clapper, on the other hand, was a device that had a simple function—it turned on an electric current simply because a user made a specific noise—and was marketed in a way everyone understood. It worked well in commercials, too.

The X10 system was the Steve Wozniak form of home automation, the ultimate tool for tinkerers that knew what they were doing; The Clapper was for everyone else.

Clapper manufacturer Joseph Enterprises was also an unusual, if effective, corporate steward. Better known for a device called the Chia Pet, the company was masterful at selling commodity products through the boob tube. Its founder, a man named Joseph Pedott, didn’t invent products, but was brilliant at both selling them and manufacturing them. He was so brilliant, in fact, that his personal papers are housed in the friggin’ National Museum of American History—a set of records that includes an oral history, photographs, business and legal correspondence, and (of course) his company’s commercials.

As American Express’ Open Forum noted in 2012, Pedott stumbled on the Chia Pet after talking to the head of sales for a drug store chain, later finding out that the owner of the idea was losing money on every sale.

He weeded his way through the supply chain and fixed the problem by cutting out the middleman. (Eventually the company moved the Chia Pet’s manufacturing from Mexico to China.)

He didn’t find the idea for the device’s catchy commercial, however, until he was sitting in a bar somewhere and a friend of his jokingly stuttered the name. Soon, he had a hit commercial and a hit brand—one that even led the company to sell its own brand of chia seeds when the seed earned an unexpected rep as a superfood.

The company sold other products, like the Scribe Ett engraving pen, the Ove Glove kitchen glove, and the Garden Weasel. Pedott, with his rep as a marketing expert, was pitched thousands of devices that he turned down. But it was The Clapper, with its catchy commercials and simple pitch, that broke through in a real way.

And its invention came about with a surprising level of drama, as it turns out.

“Plaintiff, an approximately 80-year-old woman who suffers from arthritis and osteoporosis, claims that she sustained injuries to her hand and wrist when she clapped her hands together in an attempt to activate ‘The Clapper’, a device which is designed to turn electrical appliances on or off by responding to sound.”

— A passage from Hubbs v. Joseph Enterprises , a 1993 appeals court decision based on a lawsuit filed against the owner of The Clapper because a woman clapped her hands and injured herself. The case, coming a year before the infamous “Hot Coffee” lawsuit (which, really, didn’t deserve its infamy), is probably a more deserving example of a dumb court case. The plaintiff in the Clapper case, Edna Hubbs, lost the case.

The first version of The Clapper sucked, so they had to bring in another inventor to do it the right way

Carlile R. Stevens, a serial inventor, was responsible or partially responsible for dozens of inventions over the span of roughly 50 years—including a device that was once involved in a long-running $100 million patent lawsuit. But perhaps his best-known invention was the one that gave the original Clapper a brain.

Stevens’ Smart Clapper improved on the original Clapper, patented in Canada by Peter Liljequist of Canada and Kou I. Chen of Taiwan in 1985. The earlier variation was intended to get away from all the remote controls that similar solutions, like the X10 standard, relied upon. But there were a couple of problems: For one thing, it was too sensitive, responding too easily to audio signals, such as loud noises on a TV set. For another, the inventors tried to screw Joseph Pedott out of the profits. As HowStuffWorks noted, Pedott went up to Canada, battled the men in court, and won.

That’s when Pedott brought another inventor, Stevens, into the picture. Soon enough, he developed The Smart Clapper with his co-inventor, Dale E. Reamer, and Joseph Enterprises brought the updated device on the market in 1987.

When presented with the original version of The Clapper, Stevens didn’t mince words.

“It was a Crapper, really,” Stevens recalled telling Pedott, according to a 2011 The Palm Beach Post article. “I said, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice if you had one that worked? Think how many more you could sell.’”

In their 1993 patent filing, the inventors lightly laid out the myriad ways that the original Clapper did not work correctly, in one example laying out what might happen if two Clappers were set up in a single room, and one failed to detect a set of claps.

“[I]f a person tries a second time to operate a sound activated switch that did not activate the first time, the first switch may switch an appliance back ON when the second switch switches an appliance OFF,” the patent stated.

The new version of the device had two modes—home and away—and was additionally able to handle multiple kinds of distinct claps, allowing a single device to control multiple appliances from a single outlet. By creating a version with a brain, Stevens effectively saved The Clapper from falling into obscurity, and gave Pedott another device to fortify his legacy.

Of course, even the Smart Clapper looks a little dumber in hindsight. Due to changes in electronics, the basic concept became less useful in the decades after its creation.

Our electronics in general smarter, often with functionality that is too complicated to control with an on and off switch triggered by clapping.

“The legacy built by Joseph Pedott will always be in the DNA of the company. I am honored to continue his legacy,” said Joel Weinshanker, COO of NECA. “Thanks to him, more people in America have seen a commercial for the Chia Pet or The Clapper than watched the past nine Super Bowls combined.”

— Joel Weinshanker, the chief operating officer of the National Entertainment Collectibles Association, discussing the company’s acquisition of Joseph Enterprises earlier this year. Joseph Pedott, who operated the company for 55 years and later became a philanthropist, will be involved in the company through its transition. The Chia Pet, despite some questionable diversions, has consistently sold half a million units a year for decades.

Home automation is definitely a bigger trend now than it was 40 years ago. And while X10 and other devices definitely found their audience, I’d argue that in the age of Alexa, Ring, Wemo, and IFTTT, our home automation approach ended up looking a whole lot more like The Clapper than anything else.

Certainly, The Clapper is not exactly a high water-mark for automation by any means. Its basic technology worked in a very specific context and did not keep up with the times.

But its basic marketing approach, the idea that people would want individual devices that did interesting things rather than a highly customizable complex system, essentially played out in the end.

As consumers, we don’t buy home automation technologies because they support communications protocols like Zigbee or Z-wave, the modern variants on the X10 technology used in smart homes, though maybe our contractors might. We buy Ring, because it’s well-designed, easy to install, and easy to consume. That’s the market The Clapper invented.

Just because we can automate everything doesn’t mean that we want to. Maybe we just want to keep it simple.