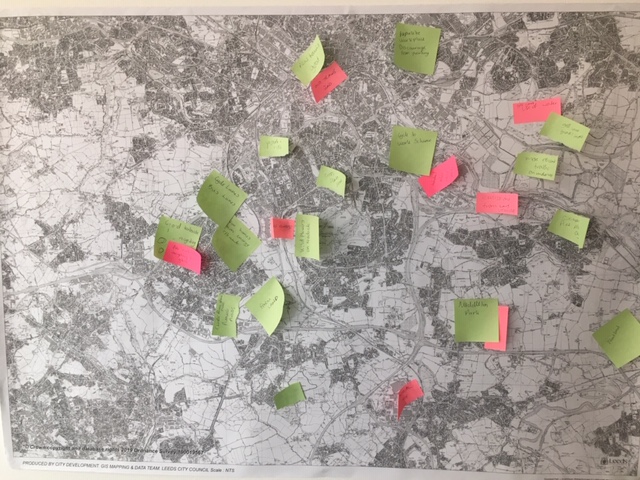

Twenty-one strangers sit in a circle on a Sunday morning in November, sipping tea and making small talk. The walls of the conference room in a West Yorkshire business centre are covered in neon Post-Its and pen-scribbled city maps. Now that everyone’s “here”, name tags are stuck on and the acoustic music is turned off, the crew can begin to tackle the question at-hand: “What should Leeds do about the emergency of climate change?”

This is the final session of the Leeds Climate Citizens’ Jury – a smaller scale version of its hot buzz cousin, the Citizens’ Assembly. In case you missed the buzz during the Extinction Rebellion (XR) protests, a citizens’ assembly is exactly what it sounds like: an assembling of randomly selected, demographically representative citizens who gather over several weeks to learn about, discuss and decide how best to tackle a political problem.

Videos by VICE

Citizens’ Assemblies are actually a pretty good way to get the ideas of ordinary people on the agendas of politicians. In Ireland, a 99-strong citizens’ assembly prompted Parliament to lift their abortion ban. In Australia, a 300-citizen assembly helped cancel construction of a nuclear storage facility. And when 60 jurors convened in Gdansk, Poland to talk flood mitigation, the mayor required the city to automatically implement any proposal that gained 80 percent of the jury’s support.

According to this crowd-sourced spreadsheet from the Sortition Foundation – the non-profit organisation that helps determine how citizens are fairly selected for these kinds of processes around the world – these are just three of 100-plus positive examples. Now, the United Kingdom wants in. Shortly after the UK became the first country to commit to bringing its carbon emissions down to net zero by 2050, XR recommended that citizens’ assemblies help design how that should happen.

“Most people are very concerned about what happens in their neighbourhoods, but feel powerless to act,” explains Peter Bryant, co-facilitator of the Leeds Climate Citizens’ Jury and Director of Shared Future. “But they don’t realise they could have a democratic system that’s more than an opportunity to tick a box every four years.”

On the ground, the atmosphere of the final Leeds session is a cross between a zippy startup break room and an earnest student council meeting. Having spent the past nine weeks hearing from “experts” – climate scientists, local politicians and business stakeholders – the jury has just seven hours to come up with a series of prioritised recommendations for Leeds City Council.

To make that happen, the assembly self-divides into smaller groups to tackle specific, crowd-decided sub-issues like transportation, recycling and funding. “Experts” are available on Skype. Co-facilitators float around to move things along. But at its heart, through polite though sometimes impassioned back-and-forth, the jurors themselves create the recommendations from start to finish.

For Debbie Wright, one of 21 jurors, that task initially seemed impossible. “I did wonder how a group of strangers who didn’t know much about the subject would be able to write recommendations,” the 40-year-old legal secretary admits. “But I was surprised at how well we all worked together and listened to each other in a non-judgmental way.”

That wasn’t the only thing that surprised Debbie. Explaining how she wasn’t initially aware that Leeds had a climate emergency, Debbie says the experience was a “real education” for her: “I thought I was ‘doing my bit’ by recycling and trying to reduce my energy usage.”

Rob Major, another juror, was in the same boat. “We got something in the post and my wife sort of said, ‘Why don’t you do this?’” the 46-year-old accountant explains. “And while I’ve got solar panels and electric cars, I wasn’t doing those things for the environment. I was doing them to save money.”

Both thought they’d be in the minority, with Debbie expecting her fellow jurors to be “eco-warriors” and Rob predicting they’d be “flip-flop-wearing environmental do-gooders”. But what most defied their expectations, they say, was realising the room’s diversity of perspective. “You did have some people where every bone in their body was an environmental bone, but you also had some who didn’t agree with calling it an ’emergency’ at all,” says Rob.

As for what brought those initial emergency deniers to the room? Some jurors say it’s because they wanted to learn more. Others came because they thought someone should play devil’s advocate. For Geoff – the staunchest sceptic of all – it was because he wanted to make some friends.

To compensate the jury for their nine sessions’ worth of time, the Leeds Climate Commission – the independent city-wide partnership behind the process – gives each juror £250 worth of vouchers and reimburses their travel expenses.

Despite the odd critic believing jurors just come for the money, Peter doesn’t think the remuneration is a bad thing. “People are so utterly disillusioned that they need incentives to get through the door,” he says. “But once they do get there, they realise there are all sorts of incentives to stay – that the decisions they make can affect people’s futures.”

By the end of this session, even the deniers have come to the table.

Last month, the jury presented the council with its 12 recommendations, ranging from taking bus services back into public ownership and cancelling the proposed expansion of Leeds Bradford Airport, to creating a more climate-focused curriculum in schools and assigning each local person a “carbon budget”. As for what happens next with those recommendations? Well, that’s up to the government.

“It would be nice to think we haven’t spent eight lots of two-and-a-half hours and then seven hours on that Sunday just to be ignored,” says Rob, worrying that the city might just pick the cheapest or easiest recommendations, if any at all. But even if the recommendations aren’t acted upon, Rob says he’s committed to staying involved, with plans to independently reconvene the jury in 12 months and do his part to spread the word.

And as for Debbie – recommendations or not – she’s already taking action.

“Since the jury, my family has been trialling meat-free days at home and thinking about whether certain car journeys we make can be done on foot,” she says. “Family and friends have come on board with this too, and I think it’s the perfect way to get people talking about any subject.”