Justino Mora, a 29-year-old software engineer and immigration activist from Los Angeles, was browsing Facebook on his phone recently when he spotted a post that caught his attention. It showed a smiling bald man in a blue uniform above the words “Now Hiring.”

“We are looking for exceptional people who can meet the requirements for a career in Customs and Border Protection,” the ad said. “Join us.”

Videos by VICE

Mora wasn’t interested: He’s undocumented, which means he’s disqualified from jobs with federal law enforcement, nor would he ever consider working for an agency on the frontlines of the Trump administration’s “zero tolerance” crackdown at the border.

But he was alarmed by what he perceived as a glaring hypocrisy. In May, Facebook announced new policies that effectively block undocumented immigrants from purchasing political ads. The change, the company said, was part of a larger effort to prevent foreign meddling in U.S. elections. But to undocumented immigrants and activists like Mora, the decision effectively meant Facebook was picking sides in one of the most contentious political issues in America.

“It shows where they really stand,” Mora said. “Facebook cannot claim publicly that they support immigrant rights and undocumented youth — they can’t claim they’re opposed to separating immigrant families when behind closed doors they’re taking money from the Department of Homeland Security.”

The ad, one of several purchased recently by the Department of Homeland Security and viewed by VICE News, is also indicative of Facebook’s larger struggle to identify and police political speech. Some of the DHS ads were initially listed in Facebook’s new archive of political content, a transparency tool created in the aftermath of the 2016 election, while others weren’t. The recruitment ad that Mora saw, and possibly others, were not listed in the archive. Facebook removed all of the DHS ads from the archive shortly after VICE News asked about them.

“We review millions of ads each day and our enforcement is not perfect — as you’ll note many of the ads were not initially marked as political,” Facebook spokesperson Devon Kearns said. “The ads were removed from the archive after we re-reviewed and determined it does not qualify as political after you brought it to our attention.”

The posts deleted from the archive included a job recruiting ad similar to the one Mora saw, with a man in a CBP uniform inspecting a vehicle. The accompanying message said, “Every day, CBP officers protect the safety and well being of our country’s citizens.”

According to Facebook’s archive, the ad was taken down because it ran without a “paid for by” label, which is now required for political content. The company introduced the measure to prevent groups like, say, the Russian government, from secretly purchasing ads that attempt to manipulate public opinion on divisive issues such as immigration.

Read: Facebook is banning undocumented immigrants from buying political ads

Facebook says it wants to verify every ad “related to any national legislative issue of public importance in any place where the ad is being run.” As part of that, it’s requiring political ad buyers to present a Social Security number and a U.S. passport or valid driver’s license, which excludes undocumented people. On Thursday, Facebook announced that it had removed 32 pages and accounts operated by “bad actors” who engaged in “coordinated inauthentic behavior” related to political issues.

The DHS ads are a test case for Facebook’s new policies. On one hand, they are clearly labeled as “sponsored” and there’s little doubt about their source. It’s unlikely that similar ads for other agencies, like the IRS or EPA would be so controversial, but DHS is responsible for immigration enforcement and the very existence of ICE has become a polarizing political issue in recent months.

Rep. Peter King (R-NY), a conservative member of Congress, has run several campaign ads on Facebook featuring images of ICE agents detaining immigrants, according to Facebook’s political content archive. One of King’s ads, which was labeled as “sponsored” and “paid for by Pete King for Congress, said ICE “does an outstanding job of defending our communities against the the brutal gang of MS-13 butchers.” King called the movement to abolish ICE “dangerous and disgraceful.”

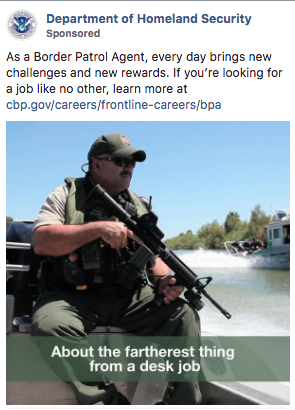

Facebook spokesperson Kearns said ads undergo “a combination of human and automated review,” but the “political label” appears to be applied inconsistently. Another DHS job recruitment post, which did not include the disclaimer, showed an assault-rifle toting white man with a mustache patrolling a river in a Border Patrol boat with the tagline: “About the farthererest thing from a desk job.” It’s unclear whether the misspelling of “farthererest” was intentional.

DHS declined to comment.

The recruitment campaign appears to be part of a broader push by the agency to accomplish President Trump’s order, handed down during his first week in office, to hire an additional 5,000 Border Patrol agents and 10,000 immigration officers.

The necessity of the additional manpower is debatable. A 2017 analysis by the Washington Office on Latin America found that each Border Patrol agent only apprehends an average of nine migrants over the course of an entire year, or roughly one every six weeks. There’s been a recent uptick in arrivals at the border, however, and the Trump administration’s sweeping crackdown on immigrants has strained DHS resources.

Trump’s 2019 budget request calls for another $211 million to spend on Border Patrol hiring. CBP’s recruitment budget nearly doubled to $12.7 million in 2017 from $6.4 million in 2015, while Border Patrol’s increased to more than $1 million from $433,000 over the same period, according to a study released in June by the nonpartisan Government Accountability Office. CBP signed a 5-year, $297 million contract in 2017 with the consulting firm Accenture to recruit agents.

Despite the presidential mandate and taxpayer money to burn, the GAO study found that DHS agencies “have consistently remained below authorized staffing levels.” Border Patrol actually lost 1,838 more workers than it was able to hire from 2013 to 2017, a net decrease attributed to difficulties filling undesirable postings in remote areas and a lengthy hiring process that makes it hard to replace workers who leave.

A 2017 report from the DHS Office of the Inspector General found that the agency wasted about $5 million by giving more than 2,300 polygraph tests to applicants who were already barred from the job due to “significant pre-test admissions of wrongdoing.”

Another Inspector General’s report last year estimated that in order to meet Trump’s hiring goal, Border Patrol and ICE would need to process roughly 750,000 and 500,000 job applications, respectively. The GAO study noted that CBP applications increased amid the recruitment efforts, climbing to 91,000 applications in 2017 from 27,000 in 2013. Still, less than 3 percent of people who apply to be CBP agents are hired, and just 1.3 percent of Border Patrol applicants ended up getting the job.

Read: How trump is using a refugee program to jail immigrant kids

Facebook would seem to offer the ideal recruiting platform for DHS, since ads can be targeted to specific demographics in certain states, like young men in California who fit the profile of a would-be Border Patrol agent. Mora who is Latino, speculated that the CBP ad he saw, which included a person of color, was specifically targeted to minorities.

Facebook’s political content archive said one CBP ad cost less than $500 and received received 10,000-50,000 impressions before it was taken down for failing to be properly labeled as “political content.”

Jorge-Mario Cabrera, spokesperson for the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles, said his organization was one of 46 nationally, including tech industry and faith-based groups, that recently sent Facebook a “private email of strong concerns” over the ban on political ads from undocumented people, but so far they have been ignored.

Kearns said Facebook has heard the complaints. “We fully understand that the process, as currently designed, presents challenges for some groups and we’re exploring solutions now to address those concerns,” she said.

Mora said he recently tried to buy political ads on immigration issues but was blocked by the new policy. Told how Facebook had deleted the Homeland Security ads from its political content archive, Mora said he was disappointed but not surprised.

“They’re telling us they’re doing everything they can, that they’re being transparent in this process and yet this is happening,” Mora said. “It’s extremely hypocritical for Facebook to say this to us and then try to cover up this information.”

Cover image: A U.S. Customs and Border Protection officer prepares to search a vehicle at the Mexico-U.S. border port of entry in Hidalgo, Texas, U.S., April 13, 2018. REUTERS/Loren Elliott