Manila is a city where some sidewalks are so narrow, you have to step aside to make room for the person walking the opposite way. Pedestrian lanes? Some people seem to think that they’re more like loose suggestions than hard rules. Bike lanes didn’t exist in many parts of the city until recently, and even now that they do, biking can feel like an extreme sport in some areas.

According to 2015 data from the Philippine Statistics Authority, population density in Metro Manila—which is made up of 16 cities—is at 20,785 persons per square kilometer. Population density, and the extreme traffic congestion that comes with it, are long-standing problems. In many ways, these issues are intrinsically linked to infrastructure.

Videos by VICE

“I honestly don’t like [architecture in Metro Manila] currently,” said architect and furniture designer Jeric Rustia. “But I like where it’s headed. There are so many young, not just architects and [urban] planners, but also stakeholders, brimming with activism and idealism.”

What might that change look like? VICE spoke with young Filipino architects and designers to imagine the Manila of their dreams, and share their designs with us. They all agree that it’s about moving away from cars, creating more open and green spaces, and, most importantly, thinking of people first.

Fewer Cars

“For so long, what has ruled our streets has been the automobile, simply because that’s what we have made the most room for, which in turn has painted our cityscape in bleak shades of gray,” said Maia Trinidad, an architecture student who prefers to roam the city by foot or skateboard.

“What if we introduced greener infrastructures and transport systems? Systems that make it easier to leave our cars at home, all in the name of creating a livelier, and ultimately healthier, city for the people that live in it?”

She thinks wider sidewalks, designated bike lanes, and tree-lined avenues will make people actually want to move around.

The lockdowns and movement restrictions brought by the coronavirus have further highlighted the way the built environment impacts people’s lives.

“The pandemic made it impossible to ignore the link architecture has with our health and well-being, and our behavior as well, in any given environment—the way we feel, think, eat, sit, communicate, interact, and collaborate with people,” Trinidad said.

Green Spaces All Around

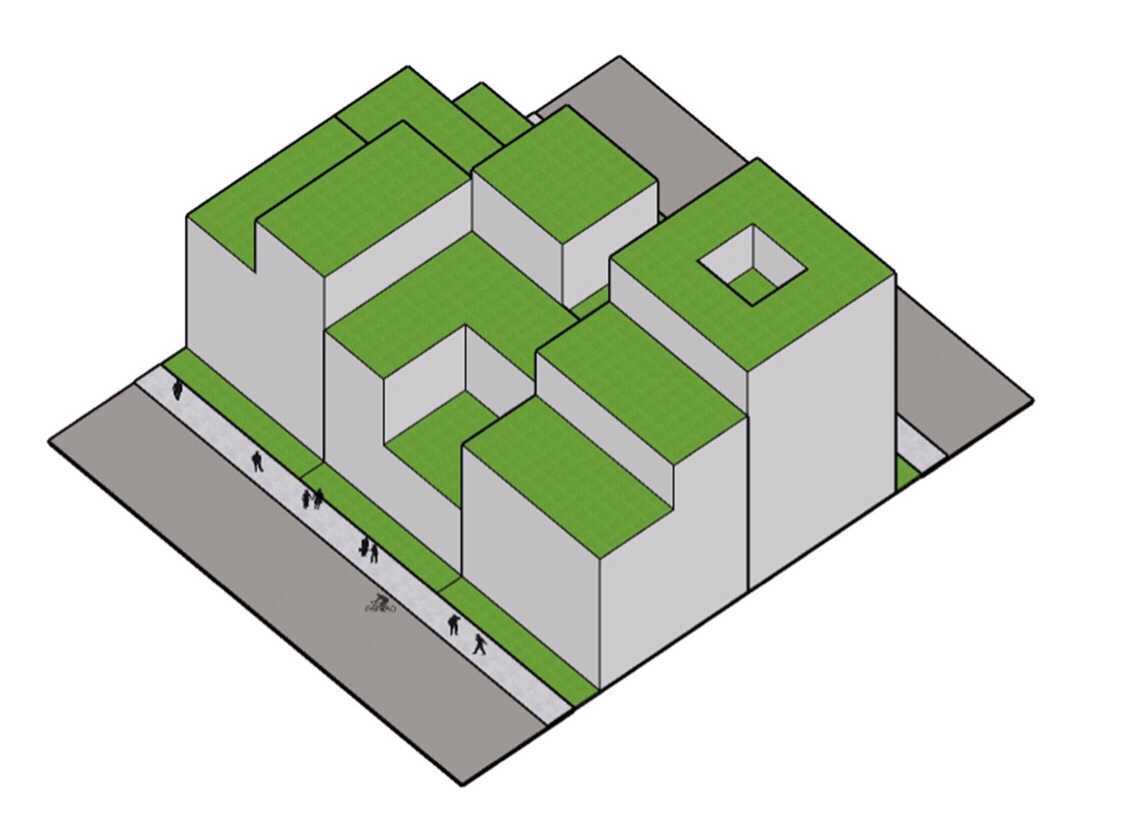

Architect Carla Lim and Designer Alessandra de la Fuente of C.A. Design House envisioned a Metro Manila similar to that of Trinidad’s dream, with more space allocated for nature and pedestrians.

“[In our images], you can see the shift from a vehicular-centric focus to a more people-centric city that allows for a safer and friendlier walkable environment,” Lim said.

The pair also painted over the drab city grays with striking colors, as symbols of the country’s bright culture.

The duo imagines similar changes to high-rise buildings. Through rooftop gardens and “breakout spaces,” like playgrounds and parks, they hope to promote better mental and physical health.

Connected Cities

Rustia said the transportation restrictions implemented during the lockdown have highlighted how important it is to democratize Metro Manila’s streets and give them back to the people, so his dream city is one built on connections and ease of movement—without all the cars.

He said his proposal “is an act of rebellion towards our car-centric society.”

His plan? To introduce pedestrian and bicycle bridges across key points of the Pasig River.

He chose three areas for his proposal. The first is the site of a vehicular bridge currently being built to connect Manila’s Chinatown Binondo and the historic walled area Intramuros. Instead of another bridge for cars, Rustia imagines a tourist bridge for kalesa (horse-drawn carriages), bikes, and pedestrians.

Rustia also imagines a pedestrian bridge that connects Mandaluyong and Makati with a straight path ending in each Metro Manila cities’ city halls, giving people easy access to business districts. Currently, only a vehicular bridge connects the two cities, with a sidewalk for pedestrians along its middle part, but none on the upward ramps. That leaves pedestrians exposed to vehicles as they climb the bridge. To get from one city to the other by foot today, pedestrians have to traverse this vehicular bridge, pass through dark alleys, and go up and down narrow staircases.

The last one is adding pedestrian and bike access to the bridge connecting Pasig City to Bonifacio Global City. The bridge opened on June 12, but Rustia said it has the same problems the vehicular Mandaluyong-Makati bridge has. “It can still be improved,” Rustia said.

Rustia, Trinidad, Lim, and de la Fuente dream of a Metro Manila that belongs to its people.

“The main idea is to give the city back to the people… by creating space for them,” Trinidad said. “To invite people to walk, bike, or even stay a while by providing them the room, elements, and systems to do so.”