Social media was born and the prototype influencer followed: Hanna Beth, Audrey Kitching and Kiki Kannibal – just a few names you’ll recognise if you were a very online millennial of a certain age and partook in a particularly melodramatic era of youth culture. These platforms – Myspace and then YouTube, Instagram, even Tumblr – were practically designed to generate “stars” like this. Celebrity was democratised with a like, follow or a declaration that you were a “fan” (lookbook.nu’s wording).

But in the early days of the 00s, becoming an influencer was more about being hot and/or cool – Beth and Kitching are prime Myspace examples – and adopting a persona-first approach than necessarily creating the “best” content. Millennial influencers realised at the same time we did that they could give us things that celebrities couldn’t: access to their lives, innermost thoughts and day-to-day commentary.

Videos by VICE

This was like having a reality star in your pocket, one who doubled up as a friend. It also quickly became clear that this was a job – a fully-fledged career.

Now that these original influencers have moved over to share the concentration span of the public with a new crop of younger influencers on platforms they and their followers might not even exist on, it’s time to pay homage to the journey they’ve been on – one which we’ve all liked and subscribed.

Lookbook Days or That Pork-Pie Hat Life

Girls wanted to move on from the three fashion options available in the mid-2000s: emo-slash-scene remnants, Jack Wills or jeans and a nice top. We needed desperate help to express ourselves differently. That’s where the ladies of the internet stepped in, from the streets of Manhattan and the bricked wall outside a Leeds Co-Op.

Lookbook.nu was launched in 2008 with the intention of making San Francisco creator Yuri Lee a lot of money, but also to make fashion readily accessible; to allow girls to crowdsource looks and rival fashion magazine spreads and Daily Mail showbiz shots of rich insiders and A-listers.

People – predominantly women – uploaded heavily filtered pictures of themselves in their outfits and subsequently received “hype” (it was the 00s) from other users, who, like me, were probably girls who thought a hair-sprayed quiff and skull ‘n’ crossbones bikini top comprised a fresh daytime look. Some of your fave millennial influencers today may have never posted their Black Milk knock-off galaxy-print leggings on Lookbook.nu, but the real heads know this was the genesis of the fashion influencer template.

Teenagers didn’t really buy much based off what we’d seen on there because a) internet shopping and fast fashion were in their infancy; b) our weekend jobs covered Glen’s vodka, bad weed and cinema tickets but not Luella Bartley handbags and c) we didn’t have the thigh gaps and self esteem present in the portraits to pull off hot pants or statement hats. That said, hypefluencers did mean there were two long years in which girls wore their forehead handbands tight and infinity scarves very, very long.

Goodbye Sun-In, Hello Touch Of Silver

Highlights had to die for influencer service journalism to live. Through videos like “How To Get Your Hair Silver White”, influencers not only taught a generation how to bleach our hair – a lifelong skill – but made having deliberately (or not, it’s hard to tell) over-toned purple shampoo hair UK street style fashionable.

There Was a Young Girl Named Lita

There’s nothing to say here other than British influencers, a wayward extension of the West Coast fashion blogosphere, really sold us on Jeffrey Campbell Litas. Kids forced their parents to take them to Camden solely to purchase knock-offs and their ultimate pairing: thigh-high faux suspender tights.

Welcome to the Dark Side

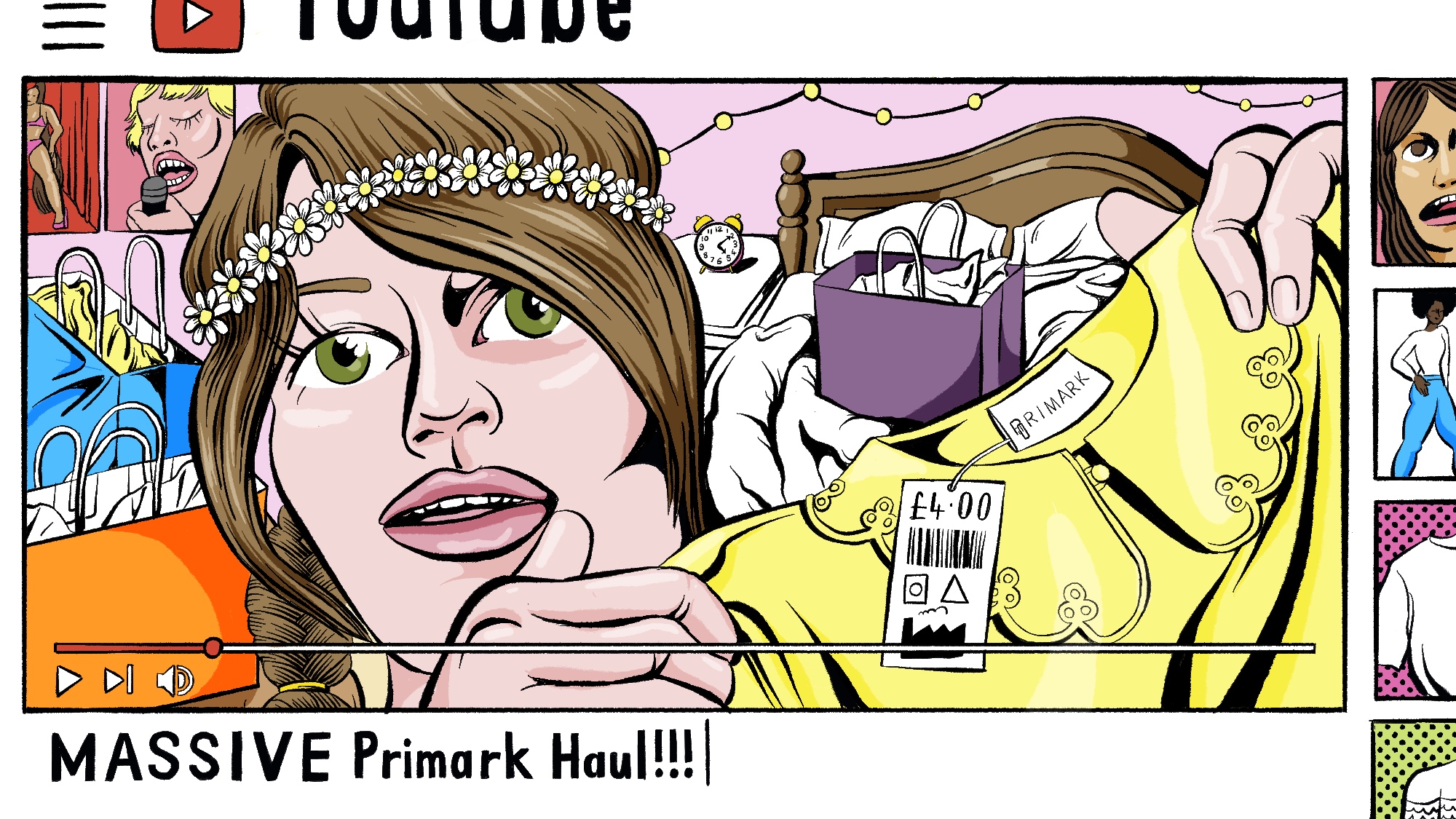

The hammy pop culture visual signifiers of excessive shopping = gorgeous life were already drilled into our brains, from Vivian Ward living that upper class life on Rodeo Drive to Cher Horowitz tottering about with bags in the opening scene of Clueless. The influencer version was the same, albeit engineered for the internet age.

By late 2010, a quarter of a million hauls had been uploaded to YouTube. Early videos were mostly influencers sharing monthly hauls of a few bits purchased bussing around the local high street and on a trip to London as a treat. Later they were shop-specific hauls, even boasting the number of items in the title of the video.

Haul culture wasn’t reflective of shopping we knew and loved as teens: occasion shopping that neatly doubled up as “hanging out”; going into town to look through Tammy or Topshop for a single nice top or to shoplift a new lipgloss. This was a conceptual shift for the young female masses to buying what you weren’t convinced about or what wasn’t even that nice. It was quantity over quality. Prior to brands sending influencers a load of product for free, the majority of influencers were just buying for the haul and then returning it anyway.

Before this genre of video was synonymous with influencing, you purchased a couple of dresses online for prom with genuine concern over whether the return would get back to the company warehouse safely. Afterwards, receiving an ASOS bag bigger than your entire body that carried a hysterical 19-item order of tat was a normal and applauded thing to do every payday. It was arguably the nadir of and turning point for influencing, something you can point to as a significant driver of our overconsumption of fast fashion.

Another One Bites the Crust

Depending on who you ask, “What I Eat In A Day” videos either trigger disordered eating tendencies or are just a devastatingly boring content format to consume religiously because you don’t love yourself.

Wherever you fall on the WIEIAD spectrum, the ubiquitousness of these videos is such that we’ve all had a confused and/or concerned dad or boyfriend walk in on us watching these in bed. What dark mindset might you be in, my loved one, to be watching such miserable instruction from a stranger?

All kinds of influencers, including minimalism lifestyle influencers and travel influencers, did these videos from around 2013 onwards. It’s strange how enduring this format is, now adopted by Gen Z on TikTok and with Love Island’s Molly Mae uploading one on YouTube a mere month ago.

The Boyfriends of Instagram, Revealed

Forget influencers unionising. For years, thousands of men across the world were forced into unpaid and uncredited creative labour, but finally the human tripods behind the camera were given space to shine.

In this era, boyfriends were introduced to us and made into monetisable, brand-building content. Influencers showed how they dyed their boyfriend’s hair or dressed them, asked them dicey questions like “what food do I hate?” or let the boyfriends do their make-up and style them. Horseplay ensued. The industrious thing about this content shift was that boyfriends could be utilised later down the line in break-up videos and Questions For My Ex-Boyfriend formats.

Girl, Uninterrupted

Followed by a shift in the discussion of mental health in mainstream media, it was suddenly OK to not be OK. In simple, stripped-back videos and posts with essay-length captions, followers learned about the anxiety that influencers experienced when social media was not just something to be relied on for connection and a self-esteem boost, but your whole income and livelihood.

Influencers also shared personal stories on relatable problems, like what it’s like being on antidepressants or finding a contraceptive pill that works for you. See also: “coming out” about a secret they’d been keeping from followers, literal coming out videos and awareness-raising on issues or personal causes.

All Grown Up: The “@zoeb92 and @AlexPT are my parents :)” Era

The teen entrepreneurs we met at the start of this article are now living the high life. They have been at their content game for a decade plus and have a long-term boyfriend. While the geriatric influencers may not be hip or relevant to Gen Z, their followers have grown up with them and remained more-or-less loyal.

The savviest influencers have found a way to monetise part of their mature life: a renovation account for their first home, a cute account for their puppy or – alienating for many but nonetheless brand deals with JoJo Maman Bébé exist – an actual baby. These accounts also provide a creative exercise in writing captions in dog or baby first person.

Ironically what should be laughably banal – we are talking about literally watching a video of people watching paint dry – has now become painfully, woefully aspirational. The emergence of this phase coincided with the oldest millennials pushing 40 in a flat share with no savings. Observing influencers doing normal adulthood things while waiting for the bare minimum to live a secure, happy life is a sign of the times.

The Future??

The meaning of the millennial influencer is in flux. Through the pandemic and Black Lives Matter 2020, influencers had an identity crisis. If I can’t flog fast fashion anymore, where do I look for brand partnerships? I usually talk about make-up and shopping to feed people’s escapism – am I still allowed to do that? I don’t know much about British colonial history but I need to post about it, and if I don’t post about it now followers will notice but I might say something wrong, so I’ll copy what the other influencers post but make my own infographic… Is that OK?

It’s been a paranoid era of self-growth. Who knows where millennial influencing will go, but it will probably never completely disappear. I was once influenced to buy a Fitbit even though I don’t exercise, and I took a trip to a city based purely on a single National Tourism Board-sponsored video, so believe me when I tell you it will never die.

More

From VICE

-

CollinRugg/X -

Budrul Chukrut/SOPA Images/LightRocket/Getty Images -

-

Amy and Stephen Allwine on their wedding day. Years later, Stephen went on to arrange the murder of his wife (Photo: Your Tribute)