On a day this past spring, the singer and actor Alex Newell perched on the edge of an old sofa in a cavernous brick building in Brooklyn, wearing a tight dress. He’d just come from shooting an interview upstairs; in an hour, he’d need to be back in Manhattan to rehearse for his new role in a Broadway musical. Given his crammed schedule, I wondered when he’d find the time to put out new music—I was introduced to his work when I stumbled across his excellent pop single “B.O.Y. (Basically Over You)” on Spotify—but I’m sure he’ll figure it out.

Newell’s talents are manifold. He’s best known for portraying the first openly transgender high school student on American television: Unique Adams, who appeared on Glee in 2012 after Newell was first runner-up on The Glee Project. The role broke Newell out of suburban anonymity in Massachusetts, where he crafted his voice in his church’s choir and navigated gender and sexual identity in his personal life. In the years since, Newell has made a name for himself as a recording artist. In 2016, he came out with his debut EP, POWER, on Big Beat Records. The release reached No. 4 on the Billboard Top Dance/Electronic Album chart, earning Newell more than 400,000 monthly listeners on Spotify.

Videos by VICE

Back in that brick building, Newell tells me about his most recent achievement—making it to Broadway. The musical Newell appears in, Once on This Island, is about a peasant girl’s pursuit of love in the colonialism-ravaged Caribbean Sea. Newell portrays Asaka, one of the protagonist’s female deity guides, a role which allows him to engage with racial identity, power, and discrimination because the story itself is centered around these issues.

For More Stories Like This, Sign Up for Our Newsletter

“I’m lucky [that] in my show, my role was traditionally played by a female in the original. [My show is] a revival of the original— and so it’s a mother of the earth [character] and I get the question: ‘Well, you don’t know what it’s like to be a mother, you don’t know what sits like to do this,’ and I’m like, ‘I also don’t know what it’s like to be a god. No one knows what it’s like to be a god—except for maybe Beyoncé.’”

Newell’s turn as Asaka reflects his own complex identity, as well: He often looks and sounds “feminine.” “I’ve gone through it so much now that everything is in a hetero mindset, and it’s going to be that way until we break down the wall of what everything is,” he said, pointing out the way that society views gender as a binary. “And so it’s like, when I get married and have kids, I know that I’m going to be the mother figure. Hell, all I wanna do is be a stay-at-home mom and just make cookies and drink martinis. I mean.”

There are just some days when he brings “her” out, and others when he doesn’t. “While I’m not 1,000 percent masculine and not 1,000 percent feminine, I know that I am heavy on the feminine,” Newell told me. “But sometimes I want to rip the hair off and be in a sweatpant!”

Newell identifies as a man, but because of the way he dresses, acts, and sounds, people often make assumptions about his gender—like that he’s actually a trans woman. For Newell himself, his gender isn’t so obvious. He’s comfortable identifying as a gay man, but submits that he probably fits somewhere beneath the transgender umbrella—he’s not sure. “I question myself [about] that all the time,” he told me. “You’re telling me that I am, so I guess I am,” Newell said, reflecting on people’s presumptions. “I’ve lived in a world where ‘trans’ is such a beautiful, positive thing in my life. I get kids walking up to me like, ‘You helped me transition; you inspired me to transition.’ I’m like, ‘I did that!’” he told me. “But then—I question.”

“When I was teaching kids how to be on Broadway, I’d never been on Broadway a day in my life. I’d just booked my first Broadway show at 25, and I feel like I was just, like, being fake—this poser,” Newell explained. “A Broadway poser. And sometimes, I’m like, ‘I’m a trans poser!’” Newell said. “Maybe I should just be trans.”

“Great, I’m in a zoot suit, living my best fashion life.”

Newell has dodged clumsy, ill-fitting, and often arbitrary gender assignations since childhood. “I always had jelly on my hips and a swish in my step,” Newell told me with a knowing glance. “There’s nothing that I could have hidden, honestly. My voice has always been naturally extremely high, for no apparent reason,” he laughs. “I never felt comfortable in my own clothes,” Newell told me. “One, because my mother was alway dressing me—always missing the mark. I’d look like a miniature version of my 45-year-old uncle. I was always like, ‘Great, I’m in a zoot suit, living my best fashion life,’” he laughed.

Newell lives at the intersection of Black, gay, and feminine. “I am the minority of life,” Newell told me, his hair curving over his brow. “I didn’t know that I was Black until someone made it known,” he said, offering an example of how identity can be social constructed.

Earlier in his life, Newell struggled to understand his place when other people told him he wasn’t the right kind of man or the right kind of Black person. As he came of age in a Black church, Newell said he was “the only boy in the soprano section,” and described how the singers were physically arranged in the sanctuary: “Girls, girls, girls, boys—Alex.”

When Newell was cast as Unique on Glee, some people in his religious community wanted to punish him for expressing his support for sexual and gender diversity on TV. A newer pastor at the church refused to let Newell sing, despite the fact he was central to the spiritual service. “I remember the shift: It’s all fun and games for me to sing the song until I say I’m gay,” Newell said.

“I always had jelly on my hips and a swish in my step.”

“My aunt, who was the minister of music, was like, ‘Alex is gonna sing,’ and sent a note over to him. He looked at her and said, ‘No.’ I was like, ‘That’s strange, because I’m pretty sure I’ve sung here since I was a toddler, I was here before you were the pastor, and I’ll probably be here after you’re the pastor of this church.’”

The confrontation with the pastor disturbed Newell—and effectively reinforced his sense of responsibility to himself. “Nobody else is going to be me,” he remembers thinking at the time.“ I’m me, and I have to look out for myself. If you don’t like my representation, that’s on you. But I, and my family, have been a pillar of this church, and I’m not going anywhere.” He held his ground. The pastor eventually left the church, Newell and his family still attend. The newest pastor plans to take a busload of parishioners out to see Newell perform on Broadway.

In Black America, there is a specific kind of pressure for boys to be masculine, Newell said. “‘Why do you talk that way?’” Newell recalled, listing the questions his peers posed to him when he was young. “‘Aren’t you Black?’ Or, ‘Why is your voice so high? Are you gay?’

There’s so much pressure,” Newell told me. “It’s more so because there are so many people of color in jail. I grew up fortunate and blessed. My mother worked very hard to make sure I went to the best of schools.”

In Once on This Island, Newell is grateful for the opportunity to play a cisgender female role that directly confronts race. Being able to shine a light on these issues through his work means a lot to him. The opportunity is especially meaningful to Newell because he has struggled, as with gender, to find where he fits within a Black identity.

He points to problems that exist within (and well beyond) the Black community, where the lightness of your skin can play a role in how you are perceived by one another. “It’s something we don’t even notice that we do,” Newell said, pointing out that many Black Americans have descended from the white American slave trade, and how that forced Black people to adhere to white ideals, including “passing” as white.

“I’m so taboo in my own African American community that they don’t even see me as Black sometimes.”

“To speak on something that’s so racial—especially something that’s so interracial—of, like, a divide that’s happening in my own culture, where just because you’re a little lighter than me, or you are lighter than me, you think that your life is that much better than mine is,” Newell said, reflecting on his experience as a dark skinned Black man. “We’re always [dealing with that]… We were in our own country, our own continent, where we were all the same, and then we were stripped from that, brought over, and then forced to have intercourse, and then have this child that we didn’t know what it was gonna look like.

“You didn’t know whether that slave owner was going to the murder your firstborn child or steal your firstborn child and take them. Or was it the passable or not passable: Did you pass for white or did you not pass for white? So these are the things that we’re dealing with in our show right now. To bring [this] to light to a community that doesn’t really understand that most days—whether that be the white community or even sometimes the Black community who just wants to turn a blind eye to it—it’s amazing, it’s wonderful to get to do that.”

“I’m so taboo in my own African American community that they don’t even see me as Black sometimes,” Newell told me. “There’s this expectation of being a Black man, of being stronger than most; having that rigid, hard back, that almost arrogant feel,” Newell told me, his full lips painted and his black eyelashes batting. “Honestly, when you strip all that back, you’re still just a human.”

Like many femme boys and girls, Newell grew up playing with dolls, which his masculine male family members reprimanded him for. “‘Be a man’—that’s what you hear so much from your uncles and your cousins. ‘Stop crying. You don’t get to cry,’” Newell recalled softly.

“I don’t know what it’s like to own up to being a man. I’m sorry—I don’t understand that. I don’t get it.”

Newell had few models for that. “My father died when I was six, so all I had was my mother to look up to,” he told me. Manhood fell on him as a great responsibility and a foreign, oppressive inheritance. Though Newell was young, still uncertain of who he was or why his gender should inform his role in his family, he was pressured to fill a role in the absence of his father. “When my father was dying, all I kept hearing was, ‘Now you’re the man of the household,’ and I was just like, ‘I don’t know what this means,’” Newell said.

“I don’t even know how to live right now,” he recalled thinking. How was he supposed to be this thing that other people had in mind for him? “I don’t know what it’s like to own up to being a man. I’m sorry—I don’t understand that. I don’t get it.’”

For young people today, this way of life is reflective of their gendered truths. As many as 50 percent of Millennials consider gender to exist on a spectrum, not a binary. People like Newell indicate that male femininity is far more expansive than mainstream society would like to believe.

As I see it, it is precisely because Newell does not pin himself to any label that he has so much power. By allowing himself both masculine and feminine modes of presentation—to appear before his audience as female, or expressing himself personally with femininity, knowing that his identity is comfortably male—Newell is projecting a life-altering message to boys and men across the nation: It is okay be a boy and to be feminine, and to embody the image of a beautiful woman the way that Newell does. Because he identifies as male and also breaks all the rules about how men are supposed to look and behave, Newell stretches the concept of masculinity so far from its starting point that the concept itself breaks apart.

“I love it,” Newell told me. “I’m in the limbo of life.” It’s something to celebrate. It is his difference from the norm that has made him a star. “I have to stick to this,” Newell said, grabbing his purse before catching a cab to Manhattan, lest he be late for his rehearsal. “I don’t know what else I can be.”

More

From VICE

-

Photo: Jorge Garc'a /VW Pics/Universal Images Group via Getty Images -

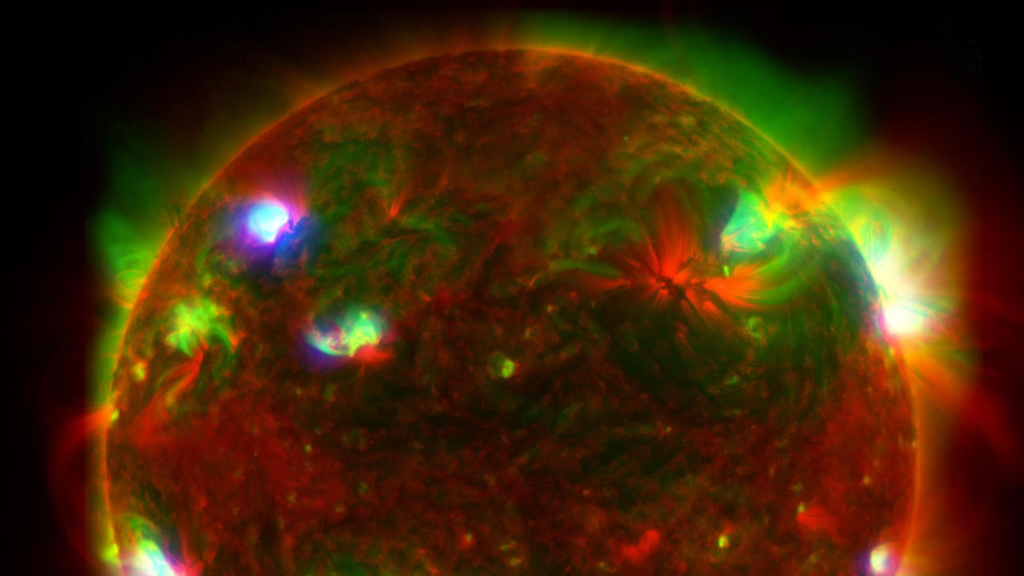

Three-Telescope View of the Sun. Photo: NASA -

Photo: Maria Teresa Tovar Romero / Getty Images -

Photo: grecosvet / Getty Images