The spiritual charge of Oak Flat, Arizona is unmistakable to Vernelda Grant. It’s where she goes to clear her head—for solace.

“When I go to the mountains that’s when I’m not alone,” she told VICE. “It’s there that I’m guided and watched over. There’s healing spirits there.”

Videos by VICE

Grant is a member of San Carlos Apache and serves as its tribal historic preservation officer. She said the area is host to a coalescence of rituals: holy ground ceremonies and puberty rites for Native American girls, a place where sweat lodges are erected and people gather traditional medicines and food, like tobacco and acorns. Reminders of their ancestors are present: Petroglyphs grace the sandstone, and there’s evidence of ancient habitation sites.

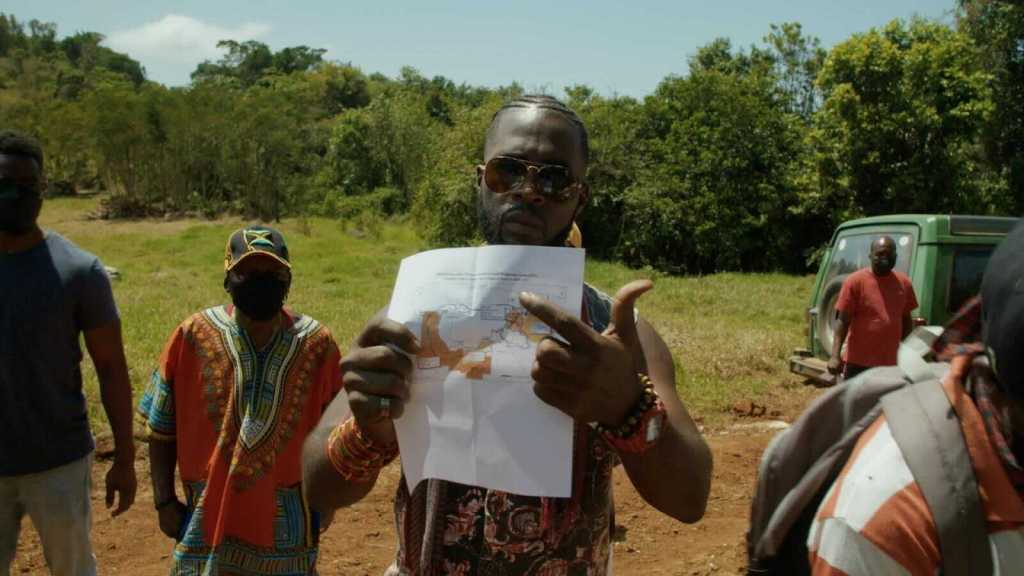

All images via ‘RISE’

“This is the ultimate place to have a healing camp,” she said. “We take what we want when we want.”

The area, located in Arizona’s Tonto National Forest, about 70 miles east of Phoenix, is included in a controversial land trade between the US government and Resolution Copper Co., an offshoot of international mining conglomerates Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton. The dispute is the focus of this week’s episode of VICELAND’s new show, RISE, which focuses on Indigenous resistance in the Americas. The copper mining plan involves the privatization of 2,422 acres of public lands in exchange for 5,344 acres of company-owned terra to get at robust copper ore deposits that lie 7,000 feet beneath the surface.

Block caving will do the trick for getting out the copper, but would leave a 1,000-foot and two-mile-wide depression in the earth in its wake, a phenomenon called subsidence. Then there’s the waste: 1.6 billion tons of it. A proposed tailings facility is located on national forest property, between the towns of Superior and Queen Valley, Arizona.

“It’s going to eliminate a whole culture, a whole people,” said Wendsler Nosie Sr., a leader of Apache Stronghold, an organization established to oppose the project. “In 15 to 20 years we’ll no longer be who we are. This is a war of evil against the mother earth.”

He’s most concerned about possible water contamination. Nosie worries the project will taint aquifers that are relied on by his tribe and multiple municipalities.

“When Resolution Copper leaves this place, all of the deep water and aquifers in that area will be contaminated,” he said. “What really pulls us together is the issue of water. Water affects all of us in southeastern Arizona.”

Now there’s another serious hurdle the Apache people must confront: President Donald Trump.

“This year’s going to be a battleground with the new administration,” he said. “If we don’t get support in the House or Senate, and definitely don’t get anything from the president, it puts places like Oak Flat in the position of being totally lost forever.”

While the region has been eyed by corporations for over a decade (all attempts at privatization have failed up until this point), the issue became critical for tribes at the tail end of 2014 when Arizona Senator John McCain and others inserted a last minute proviso into the National Defense Authorization Act of 2015, which green-lit the land transfer. It’s legislation that must be passed every year, one which former US President Barack Obama eventually signed off on. Project supporters, like McCain, posit timeworn benefits of job creation and economic stimulus.

Apache Leap— a site steeped in history, where Apache people plummeted to their death to avoid being captured by the military—will be spared, according to US legislation. But that is little consolation for the community.

On February 7, Apache people will have occupied Oak Flat for three years, according to Nosie—and the number of demonstrators swelled to over 1,000 at times. Their plight was picked up by publications like The Guardian and the New York Times. And Apache tribes plan to do the same this month.

Repeal bills were submitted after the NDAA dropped: one from Arizona Democrat Raul Grijavla; another from Senator Bernie Sanders. Both are titled “Save the Oak Flat Act,” and both attempted to rescind section 3003 of the defense bill. But little progress was made in congress.

Another repeal bill will be introduced this year to protect Oak Flat in its entirety, said Nosie.

In the meantime, the land exchange and Resolution Copper’s project must adhere to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and produce “a single” environmental impact statement. The US Forest Service is responsible for analyzing the project’s operational effects and possibly enforcing mitigation measures in response. Forest officials received comments from the public and stakeholders in 2016. Federal lands will be transferred to Resolution Copper 60 days after the impact statement is published, said John Scaggs, spokesperson for Tonto National Forest.

“The projected timeline for the entire process is typically somewhere between five and ten years,” he said. “Forest service officials have consulted with various Native American tribes and will continue to do so. We are listening to their concerns and taking those into consideration.”

Scaggs echoed Nosie’s concern over water. “The Tonto National Forest is also concerned about water,” he said. “It’s one of several issues that is currently being analyzed by the forest service.”

RISE airs Fridays at 9 PM on VICELAND

Follow Julien Gignac on Twitter.