This story is part of a wider editorial series. Coming Out and Falling In Love is about the queering of our relationships with others, and the self. This month, we look at Asian attitudes to sex and porn, dating in the digital era, experiences of LGBTQ communities, unconventional relationships and most importantly, self-love. Read similar stories here.

Andre Santos is a copywriter for a major advertising agency in Manila. An out and proud gay man, he’s the first to admit that Philippine society still has a long way to go when it comes to LGBTQ rights. Still, he’s happy that the conservative country is now more accepting of members of the community.

Videos by VICE

“That’s especially visible in how gay lingo has penetrated and fused with our vernacular,” Santos told VICE.

This lingo he’s talking about is the “Beki language,” the colloquial term for gayspeak in the Philippines.

If you find yourself in any Filipino social, your ears are bound to catch familiar terms in a very different context. “Indiana Jones,” for example, does not refer to the Harrison Ford action flick but a term that means “to not show up.”

It’s confusing, but don’t worry, we’ll enlighten you soon.

Although often used to poke fun and make conversations lighter, Beki talk is complex and a way for the gay community to bridge the differences in the country’s many languages. It hides common words under borrowed terms from native dialects, as well as American, Spanish, and Japanese pop culture. The language is so diverse that there’s even an entire dictionary dedicated to it. It has also made its way to hit TV shows, songs, and everyday conversations between gay and straight Filipinos alike.

“I learned how to speak gay lingo from my friends back in college. They would use it in their daily conversations, face to face, or when they would text me. From there, I started to catch on,” Arthur Tan, a DJ and musician who identifies as straight, told VICE.

Every Filipino knows at least some Beki words. There’s “besh,” a term many use to describe a close friend. There’s also “kabog,” which means “to lose.” Everyone — from boomers to Gen Z, professors to students — use these words in everyday conversations.

“The thing about gayspeak is that it’s a social dialect, built by a community who needed to communicate discreetly or on their own terms,” Tuting Hernandez, an Associate Professor of Linguistics at the University of the Philippines and founding member of the LGBTQ student organisation Baybaylan, told VICE.

This is similar to inside jokes between friends and jargon in professional communities. Hernandez noted that Beki languge is veiling, which means that the gay community built the terms to hide what they truly intend to say.

“It was a way of avoiding cultural violence. Now they can talk about so many different things without society eavesdropping on them,” he said.

And it continues to evolve. Now that some Beki words have made their way to mainstream slang, those in the gay community have found new ways of talking. One example is through wordplay using names of celebrities.

Like that Indiana Jones reference.

Here’s another: the Beki term “keri” (which means “okay”), has now evolved to “Keri Kylie Minogue and Dannii Minogue in tow.” It’s confusing to people who are out of the loop and that’s the point.

Gayspeak has also learned to evolve with time and space. It varies in the different islands of the Philippines and it is hyperdynamic, which means that at any point, there can be different words for the same definition.

Across different regions, there’s “aketch” and “akis,” but they are both used to refer to one’s self, like “I.” There’s also “watash” and “anetch,” which mean “what?”

While the history of gay lingo in the Philippines is murky, there were early signs of it seeping into mainstream culture as early as the 70s, when the term “Bongga” (which means “extravagant”) was used on television shows and songs.

“Since it is a social dialect, as long as the first two gay people in the country existed, who knows what they could have come up with together? Whether it be mundane or salacious, it was a way of expressing identity and solidarity and mainly served the deeds of that community,” Hernandez said.

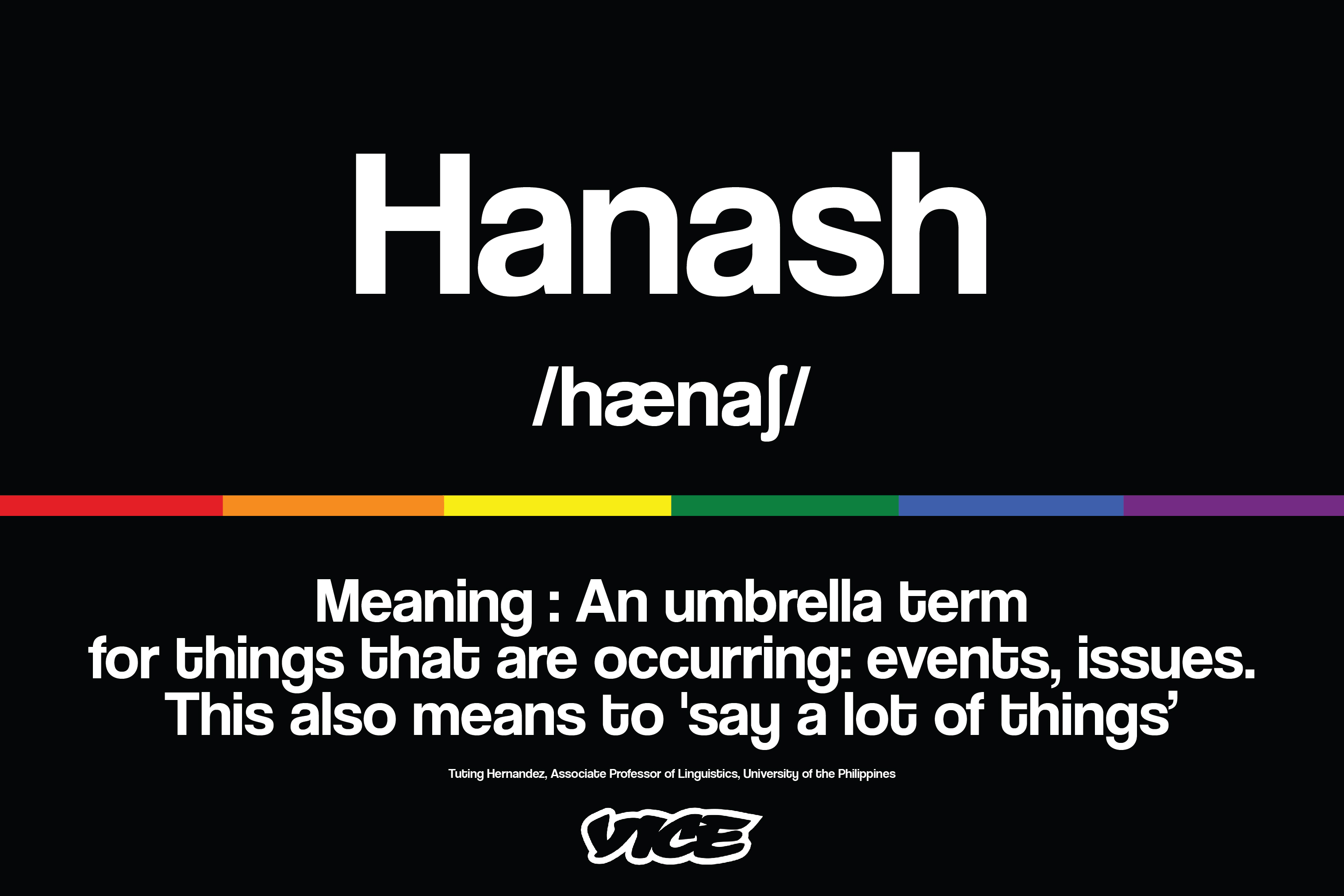

The language also tells the struggle of the gay community. For example, the term “hanash,” which means “to say a lot of things,” originated from the Japanese word “hanashi.” It became popular in the Philippines at a time when gay men, struggling to find jobs at home, started to work in Japan as entertainers.

But if Beki was meant to keep people out of the loop, how did people catch on? Why is it so popular today? Much like with anything in pop culture, Hernandez said that it’s simply because it’s cool.

“It appeals to the youth. It’s different, subversive — something their parents are not aware of,” he said.

Of course, the fact that there are many gay men in Philippine media plays a role. Arguably the most popular celebrity at the moment is Vice Ganda, who started out as a stand-up comedian in gay bars. He now hosts a variety show on TV from Monday to Saturday and stars in box office hits every year.

It’s true for those behind the scenes too.

According to Hernandez, many gay writers started in show business because it was a “safe space” to be themselves.

“In the 70s or 80s in the Philippines, it was hard to find a job … if you were out of the closet,” he said.

The mainstreaming of Beki words has led to people like Arthur Tan, straight men who use gayspeak in everyday life. His favourites include “mars,” which is a term of endearment for a close friend and “bes,” another word for best friend.

“I like how creative they are with making the different words or slang. One of the first [words] I learned was ‘Tom Jones,’ which means ‘hungry.’ I found it really interesting how they could associate that particular word and make their own language. The etymology behind each slang is interesting to me,” he said. (Tom Jones came from the Filipino word “gutom,” which means hungry)

Of course, with Beki’s rising popularity comes conversations about cultural appropriation. Some fear that straight people could be using it to mock the gay community, but others argue that it’s the context that matters.

“At times, it does feel surreal to hear boomers or whoever straight up say lingo you’ve only heard in close circles,” Santos, the copywriter, said. “But as long as there’s no negative undertones or particular discrimination, I think the community understands and accepts the adoption of gay lingo into the mainstream.”

He likened it to how drag ball culture was suddenly brought into the mainstream by Madonna’s song (and its music video) Vogue back in the 80s. It’s also similar to how American gay slang became mainstream because of Twitter culture and RuPaul’s Drag Race.

Hernandez had similar thoughts. “If you use it to mock them then that’s when it’s wrong, but if it’s part of your linguistic repertoire then it should be fine,” he said.

“All social dialects borrow from each other and it’s not just gay lingo contributing to the mainstream language now. That’s just part of the language dynamic of society, English in itself is composed of borrowed words from different sources.”

And it looks like Beki is here to stay.

Hernandez said: “If it serves the purpose of the community, and as long as the community needs a way to talk about experiences then there will be gay lingo, and there will be gayspeak, and it will evolve.”

Here’s a quick guide to some Beki words so you don’t get lost in translation: