This article appears in VICE Magazine’s October Prison Issue

When construction was completed on the Penitentiary of New Mexico in July 1956, officials were so proud they opened the doors to anybody interested in touring the facility for free. “We’re asking parents to bring their children along if the youngsters have reached the age where they can understand the significance of a penitentiary,” warden Harold Swenson told the public. “The visit might save a child.”

Videos by VICE

And so they came, more than 10,000 of them, out of Santa Fe and the isolated northern counties. The Madrid highway was choked with traffic, whole nuclear families donning Sunday’s best. They played with the grilles, sat on convict cots, turned knobs. One teenage girl said she liked the joint but thought the cells were too small. Paul Madigan, the warden at Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary, came from San Francisco Bay to offer his blessing. The governor gave a short speech. A small boy sat in the gas chamber and shouted, “Look, Grandma. I’m being electrocuted!”

By August 8, the prison was full of inmates. They spent that lazy Wednesday evening being treated to a CinemaScope picture. They were lucky to be there. The media had called their previous residence, the crumbling brick jailhouse in downtown Santa Fe, a “fire trap” and an “eyesore.” Just three years earlier there had been a riot there during which inmates spent hours attacking other prisoners and holding guards hostage. In contrast, the Albuquerque Journal described PNM as “probably the most modern penitentiary in the world.” Reporting for the Journal, Rob Beier wrote: “The recreational facilities will surpass most any high school in the state and the rehabilitation facilities, which include the school, sign plant, shop and block-making plant, have no peer in any institution in the country.”

But within 25 years, overcrowding and mismanagement turned the most modern penitentiary in the world into a national disgrace. Inmates slept on the floor. The facility was filled with rats. On one Thanksgiving the cafeteria fed the population rancid turkey; the plumbing was choked with diarrhea and vomit for days. Guards used coercion to maintain control, spreading rumors that certain inmates were snitches and letting convict code take over. Correctional officers were also physically abusive themselves, kicking inmates down flights of stairs or opening cells in the middle of the night to beat them while they slept. Even the Protestant chaplain had been alleged to wield a baton.

By 1980, paranoia and revenge ruled the prison, and the inmates decided to take over.

Many have heard of the Attica riots, but few know that what took place in Santa Fe that February was more violent and cruel. The siege lasted 36 hours. During that time, 33 inmates were tortured, mutilated, and killed by roving execution squads of prisoners high on Demerol and from huffing paint thinner. The violence remains unprecedented in American prison history. One inmate used a razor and a towel to tear a supposed snitch’s head loose, at which point he placed the head on a broomstick and walked through the main corridor, holding the stick in one hand and masturbating with the other. Governor Bruce King feared that storming the riot with National Guardsmen would lead to another Attica. Instead officials waited outside the gates, listening to screams bellow out along the high desert plains. The warden communicated with inmate leaders via walkie-talkie.

The siege ended when a handful of hardcores were guaranteed transfer to out-of-state facilities. Four months later, the state Attorney General’s office released a two-part investigation, citing metastatic corruption and incompetence as the root cause. But nothing really changed after that, and in August 1998, Old Main, the name by which the institution had come to be known, closed in disrepair.

The facility was mostly forgotten until a decade and a half later, in 2012, when New Mexico began planning events to celebrate the state’s centennial. Governor Susana Martinez called on all state agencies and local authorities to organize centennial events that would engage the public. Albuquerque held a concert featuring everybody from Los Lobos to the Bethlehem Baptist Church’s Steppin’ for Christ praise dancers. The many museums of Santa Fe invited guests to give presentations on the history of art in the desert Southwest. The Department of Health staged a film and lecture series on 100 years of Hispanic health improvements. The Corrections Department wasn’t exempt from the directive, but its secretary, Gregg Marcantel, was at a loss. It is, in a fundamental sense, the department’s job to keep its day-to-day goings-on independent from the public.

Eventually, though, Marcantel alighted on an idea. Throughout the 2000s, Old Main, just a few hundred yards from where 800 of the state’s inmates continued to be housed, lay abandoned. On occasion, it had been rented to Hollywood for $1,000 a day to shoot films such as All the Pretty Horses and Zero Dark Thirty. But for the centennial, Marcantel thought the site could be better used to tell a different story—its own. He directed the department to organize tours of the facility centered on the history of the deadly 1980 riot. Fifty-six years after Harold Swenson proudly opened Old Main’s doors to reveal the state-of-the-art institution to the public, citizens were welcomed in once again, this time to tour its wreckage.

A guide leads a group through Old Main. In 2012, the New Mexico Corrections Department opened the facility for tours telling the story of a deadly riot that took place there in 1980. Photos by Christian Filardo

The riot at PNM was set in motion on Monday, January 28, 1980, when an inmate in Old Main’s E-2 dormitory known as Blabbers filled a Hefty bag with water, fruit, yeast, and sugar, and hid it in a shower pipe chase. E-2 was a barracks-style dormitory designed to house prisoners deemed trustworthy enough to live outside the confines of cells. Six weeks earlier, ten inmates had escaped the penitentiary with relative ease, embarrassing officials. To save face, the governor had allocated money to renovate Cellblock 5, which housed those considered so dangerous that they spent most of their time idle. In an inexplicable decision, its convicts were transferred to E-2 until construction was completed. Since then, the dormitory had been under the control of a bulk of Cellblock 5 inmates, with the remaining prisoners—petty thieves and drug addicts—subservient to the more hardened cons.

Radios blared at all hours, playing disparate stations. The toilets backed up. Because some inmates were forced to sleep on the floor, fights were common: a hand stepped on, a forehead kicked. Small emergency lights meant to illuminate the dorm at night often shorted, sending the room into total darkness; in it, inmates settled scores, fucked, or screamed simply to create chaos. Guards—outmanned and undertrained—were reluctant to step foot inside. This reluctance gave the prisoners carte blanche to perform many illicit tasks, including brewing beer.

Five days after Blabbers hid the bag, another inmate, Danny Macias, pulled it out. “We had a lot of sugar and a lot of yeast,” he said later, “and that creates a lot of alcohol, and when I went up there to get it, I brought it down and I opened it… Oh, it’s powerful stuff.” Macias and some others started drinking the hooch around eight that evening and stopped briefly when guards came to check on them at 8:40. “How they didn’t smell that stuff is beyond me,” he said. “It smelled like a brewery in there.”

Within just 22 minutes, inmates commanded the entire institution.

In all likelihood the correctional officers chose to ignore the smell. Many guards were high school dropouts—some still teenagers—and training sometimes consisted of showing up on day one to put on a uniform. Between 1970 and 1980, five separate wardens sat at the prison’s helm, each offering radically different approaches to penal operations. This led to frustration among staff. Regardless of the warden, correctional officers were underpaid, making an average of $9,000 a year. The annual turnover rate stood at 80 percent. Out of fear or exasperation or negligence, officers were known to cut corners. Some pencil-whipped their headcounts, signing off that everyone was accounted for without actually making rounds.

When the guards eventually left, the dormers got tanked. They began talking about jumping the COs and taking over the pen. Around two that morning, during final count, Macias and another inmate rushed the guards. The entire dorm soon joined. They beat COs on duty and broke into the control center. Within just 22 minutes, inmates commanded the entire institution.

An abandoned cellblock

Convicts broke into the pharmacy and consumed Demerol. They found paint thinner in the machine shop. Others broke into the warden’s office and set fire to inmates’ case files. Somebody doused the gym in gasoline and lit a match. In the delirium and smoke, execution squads formed. They donned ripped sheets to hide their identities. One prisoner cut a hole in an American flag and wore it as a poncho. The construction crew working Cellblock 5 had left behind acetylene torches, and the execution squads broke into the site and stole them.

Their attention soon turned to Cellblock 4, which held protective custody: snitches, child rapists, the non grata. The largest contributing factor to the atmosphere of paranoia inside PNM was that of the “snitch-jacket game.” A tool of coercion used by officers, the jacket worked thusly: If an inmate refused to inform, an officer would simply tell the cellblock that the inmate had indeed informed; equally often, if an inmate was disliked by an officer, that officer would spread rumors throughout the cellblock that the inmate was a snitch, hanging a jacket on him.

On a daily basis prisoners had to navigate a hellacious game, forced to walk a high wire between remaining true to fellow convicts and staying on the good side of the officers. Since having a jacket hung on you was akin to a death sentence, many victims sought protective custody. Cellblock 4 inmates wore uniforms distinct from those in the general population. They were marked, rat or not, as worthy of death. Only protection from guards kept them alive.

On a daily basis prisoners had to navigate a hellacious game, forced to walk a high wire between remaining true to fellow convicts and staying on the good side of the officers.

Immediately after the takeover, captured guards were forced into mattress closets to be used as bargaining chips in the inevitable negotiations with prison authorities. Without guards, CB4 had no defense. Inmates inside used bedframes to block the doors of their individual cells. This only delayed the inevitable. Informants trembled while, nine feet away, their soon-to-be executioners used the torches to cut through the cells’ bars, all the while telling each victim what awaited.

Inmates were castrated, kept conscious via smelling salts, and forced to eat their own genitals. One was shot point-blank with a tear-gas canister, crushing his skull. An inmate on the third tier was hanged; the rope broke and he fell to the basement. He was still alive, and a group gathered around him with pipes, shouting, “You won’t die, will you? Die, you fucking snitch.” One inmate sat in his cell for two hours singing the Eagles’ “Take It to the Limit” while executioners cut through his cell bars. Once inside, they beat him, dragged him onto the gangway, and cut through his flesh with a torch. One informant had an angle iron drilled through his ear.

A south-end dorm was transformed into a rape factory. One inmate said that 23 separate attackers had sodomized him. Pipes exploded. The corridor flooded. The pen was both on fire and drowning. Terrified inmates found a way outside and rushed into the snow, pleading for help from state police. Officials looked on.

The governor had given orders not to storm the prison as long as guards were kept alive. He viewed inmate-on-inmate violence simply as collateral damage. Thirty-six hours passed before negotiations put an end to the siege. Thirty-three inmates were dead. Two hundred more and seven COs had to be hospitalized. If one wonders exactly how New Mexico perceived the value of those incarcerated, look no further than the words spoken by then state senate majority leader C. B. Trujillo on a late-night TV show. Discussing the handling of the riot, the senator said, “The fact that nobody was killed in this major uprising is certainly a credit to the governor.”

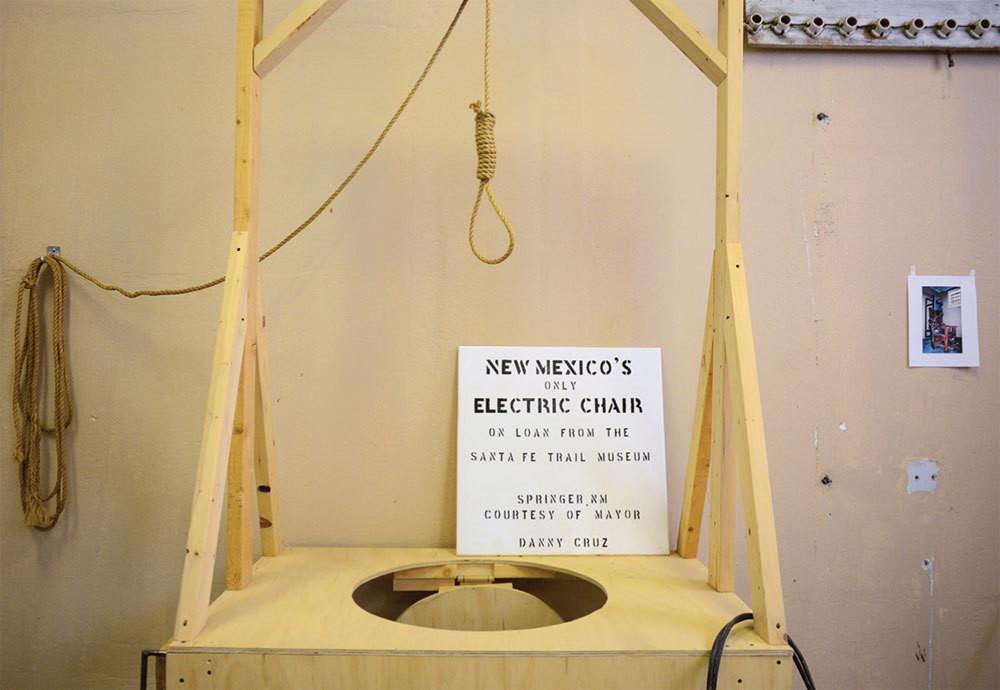

A noose hangs above the site of the prison’s old electric chair

By the time the first centennial tours took place in February 2012, state officials had come to recognize a version of events more in line with reality. The tours, which were by invitation only, led people connected to the riots and interested in criminal justice through the derelict building, where much of the original architecture and equipment remained. Though they followed no script and were guided by a varied and imprecise collection of people, they gave a detailed account of the riot.

Attendees were asked to brave snow and ice and temperatures in the single digits; to forego bathroom breaks, food, and water; and not to close cell doors behind them, as nobody had keys. Fallen tiles lay along the corridor. Every so often, a dead pigeon could be seen. In the basement, near the gas chamber, the air was of such quality many visitors gasped and coughed, their eyes watering.

The tours were nonetheless a massive success. A total of 2,000 people visited, and the Corrections Department decided to expand them beyond the centennial celebration. When they posted $15 tickets on their website for the first Friday of every month, the tours sold out in days. They added Saturday. Those sold out within weeks.

Officials saw potential, and in March 2013 they hired Alex Tomlin, a local television reporter, as public affairs director. They gave her the duty of moving the enterprise toward a legitimate museum-going experience under the banner of “Respecting Our Past to Create a Better Future.” Tomlin was to write a script based on the attorney general’s report that each guide could follow, and she began to brainstorm ways of making the experience unique. Corrections secretary Gregg Marcantel also had ideas: opening the prison barbershop and chow hall for visitors and staffing them with current inmates.

Old Main lies within walking distance of the current Penitentiary of New Mexico, and inmates in orange jumpsuits are awoken at the break of dawn each day to mop the riot site for tourists. The new tours end in a gift shop, where visitors can shell out for goods handmade by men currently incarcerated. The courtyard in the center of the facility was turned into a Meditation Garden, once it was cleared of weeds and debris by the hands of current prisoners. They provide cheap labor for what some see as an amusement park in its infancy.

Indeed, the opening of Old Main to outsiders did not meet universal acclaim. Why allow strangers to gawk and photograph the site of mass carnage and civil rights violations? Why not tear the fucker down? To allay the skeptics, the Corrections Department held a special “Survivors’ Tour” in October 2013 for former inmates and guards.

“When we did the tour, I was kind of amazed at the difference in feeling, respect, and feedback,” Tomlin said. “Since then, we haven’t had a single ‘tear it down’ comment.” Gary Nelson, who was locked up in Old Main on the night of the riot, was one of the former inmates to attend. “In a sense, seeing the prison did provide me a sense of relief,” he told the New York Times after the tour. “It’s over, you know? I’m never going back in there again.”

The defunct gas chamber

Not everyone associated with what happened in 1980 was satisfied by that gesture. Former correctional officer Marcella Armijo has been critical of how New Mexico has handled inmates’ and guards’ rights in the aftermath of the riot. She passed on taking part in the Survivors’ Tour, and when the Corrections Department wanted to award her a medal of honor for her service during the riot, she declined. “A medal the size of a quarter? No, thank you. Fuck ’em,” she said.

Armijo has the distinction of being one of the first female correctional officers in the nation to work in a men’s prison. In 1985 she became a captain at PNM and was honored ten years later with the Trailblazer Award by the New Mexico Commission on the Status of Women. She was scheduled to work the line the night the riot began but had gone out with friends earlier that evening and had had too much to drink. The next morning, at five, her mother woke her. There was footage of the burning penitentiary on the local news. Armijo immediately went out to the pen and spent the rest of the siege listening to screams emanating from the building. She watched friends carried out on stretchers.

“It’s hard to accept what the prison is doing now. Maybe I’m real negative. I’m sure if I were to talk to Marcantel and all those guys they’d think I was a know-it-all,” Armijo told me. “I just don’t want them to continue doing shit that’s for naught.” After retiring in 1998, Armijo found that her life was spiraling out of control. She drank heavily and lashed out at friends. Only later was she diagnosed with PTSD. She views the tours in part as a glossy advertisement for the Corrections Department, a tool by which they can cover up the incompetence that still plagues New Mexico’s penitentiaries.

Armijo has been embroiled in a lawsuit with the state for decades, claiming that she and 179 fellow guards were never fully compensated. She also pointed to a lawsuit filed this February by five COs claiming sexual harassment and a violation of their civil rights. “My main point is that the state never helped us,” she said. “It took a toll on my whole family. I went through hell.”

She isn’t alone. Dwight Duran Jr.’s father was an inmate at Old Main until just 12 days before the riot. The elder Duran hand-wrote a lawsuit on inmate conditions at the facility from his solitary cell and had it smuggled out in 1977. The document eventually resulted in what is now known as the Duran Consent Decree, a landmark set of reforms regarding living conditions and mental health treatment in New Mexico prisons.

Not long after its implementation in New Mexico, similar decrees sprouted up across the country. Dwight Jr. said Marcantel and the Corrections Department approached him about donating some of his father’s documents to display in Old Main. He declined. “I’m not saying my dad deserves a Nobel Prize, but he did do a lot,” he told me. “They weren’t too interested in giving him a lot of credit, so I wasn’t too interested in helping them out.”

It’d be cheery to say the riot proved edifying for New Mexico’s treatment of prisoners, but violence persisted. In the decade that followed, 14 more inmates and two officers were killed at Old Main, and hundreds of inmates and staff reported being assaulted. Thirty-eight escape attempts occurred, many of them making what took place in Dannemora, New York, earlier this year look comically machinated. In 1998, the same year Old Main closed, a judge overturned the human rights requirements of the Duran Consent Decree.

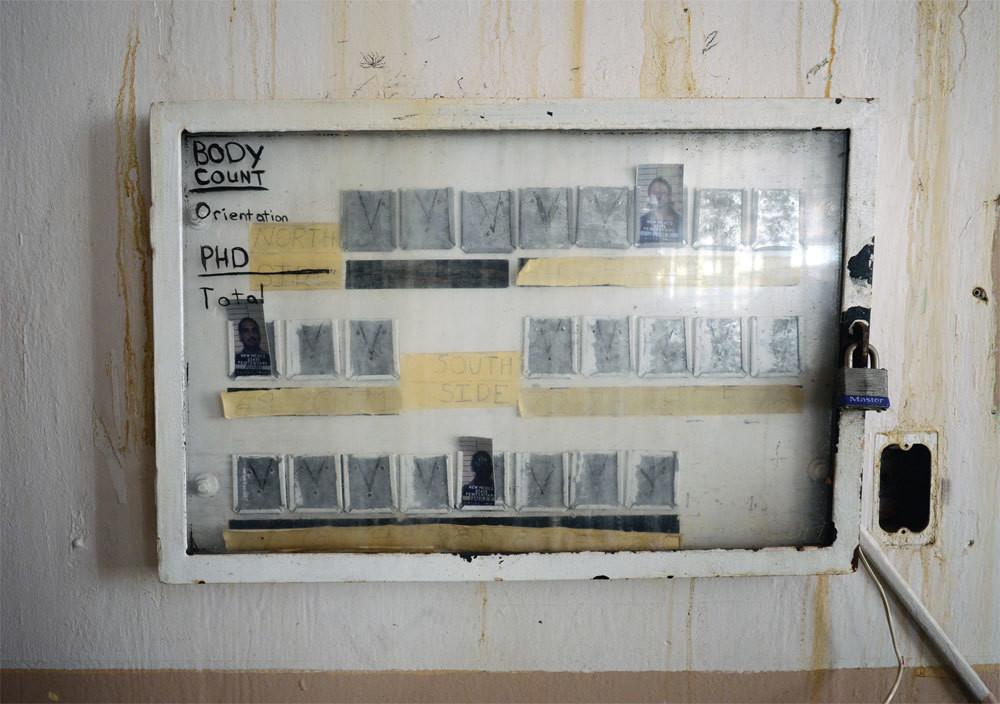

A board used by guards to keep track of inmates from when the prison was operational

On an unusually hot morning in July, I rode a shuttle from the Corrections Department central office to the drafty, high-ceilinged lobby of Old Main to take the state’s two-hour tour. Among the ten other tour-goers were a college-aged kid working on a report for summer school and two women from Durango, Colorado, wearing matching Louis Vuitton handbags. Though they didn’t know much about the riot, the pair had read about the tour in a brochure at their hotel and thought it would be an interesting experience.

Upon arrival, we were guided to a desk behind glass where we were each assigned an inmate number and then led to a height chart taped to a door for a “booking” photo. A worker in a polo shirt embroidered with the words “OLD MAIN AMBASSADOR“ attempted to calm an elderly woman in the group who looked particularly aghast. “It’s just for fun,” he said.

The tour allows people to experience a permanent nightmare in the American collective conscious: prison.

Most of the people tapped to be tour guides are reassigned correctional officers. Our guide, Cory, had worked on the line for four years before moving to a gang investigation unit. He walked backward as he led us down the main corridor toward the old control center. “I never turn my back on anyone inside an institution,” he said. “Not even civilians.” In the control center, a plastic clock is permanently set to 2:02 AM, the time it was destroyed by Danny Macias and the raiding E-2 inmates. Despite the presence of these clocks throughout the facility, the tour is almost Joycean in its nonlinearity, an outcome of Old Main’s architecture and the fact that whole areas of the institution are still off-limits. Visitors are forbidden from taking photographs in certain wings, including Cellblock 4, where the outline of a trucker burned to death is visible and the hack marks done on another inmate’s neck still scar the concrete. Though the tour guides have been encouraged not to shy away from the bureaucratic fuck-ups that led to the riot, if you don’t have a working knowledge of the events, the meandering may leave you with more questions than answers.

But it didn’t seem like people tour Old Main looking for answers. When the Corrections Department decided to open up the facility to visitors, it hit upon a fundamental shift in the nature of tourism in the past few decades. No longer are we content to slather ourselves in Banana Boat and catch a few rays of sun. Instead, we often want to use our vacation to take behind-the-scenes looks at sites of misery and death, a practice that has been called “dark tourism.”

The anthropologist Erika Robb Larkins has argued that dark-tourism sites can be divided into two distinct categories. Sites of the first kind take an “in context” approach—museums and curated locations where labels and narration are meant to educate and to contextualize the violence of the past. In contrast, there are the sites of violence left largely empty, lacking narration or structure, and meant only to speak for themselves. They’re attractive simply for still being around.

Items made by current inmates are sold at Old Main’s gift shop.

The tours of Old Main, with their loose grasp of the story of the deadly riot and its consequences, lean more into the second category. It’s not a museum but a place that communicates the heaviness of its history. Visitors were indulging a curiosity about the fantastic violence that had taken place there and reveling in it.

But the appeal isn’t merely that Old Main is the site of a particular atrocity, in the way that Auschwitz and the September 11 Memorial are. It’s also that the tour allows people to experience a permanent nightmare in the American collective conscious: prison. From the way that visitors are jokingly booked like inmates to the plans for a prisoner-staffed barbershop and mess hall, the darkness of the tourism is playing pretend at living in the hellish parallel reality of American prisons. For the price of a cheap lunch, we enjoy the experience of savagery while knowing soon enough we can retire to the La Fonda hotel bar for an afternoon margarita.

As we moved from the corridor to Cellblock 4, we were told to put our cameras away. The sun came in through the windows facing north. Outside, if you squinted, you could see Santa Fe. The afternoon before, a rare thunderstorm had moved across the Sangre de Cristo Mountains and onto the plains, and the cellblock’s basement held pools of stagnant rainwater. After showing us the burn marks, the hatchet scars, the places where inmates were tossed from the top tier, Cory eventually led us to the gift shop, where inmate-made tortilla rollers and a combination coffee mug/shot glass called a “mug shot” were for sale.

I purchased a large Old Main T-shirt. On it, a vato in Ray-Bans opens a prison-issue denim shirt, revealing not his chest but the correctional institution. While paying, I overheard one of the women from Durango ask Cory about future plans to clean the museum up. Our guide quickly corrected her. “This isn’t a museum,” he said with a sly smile. “If it were a museum, everything would have to change.”