One of the best Canadian films of the 21st century turned 20 last weekend, and we’re lucky it exists at all.

For all of its eventual success and cultural resonance, _Ginger Snaps_—a feminist horror film—fought an uphill battle to get made. The production was plagued with scheduling setbacks and various obstacles from both the film industry and a perfectly ill-timed cultural panic.

Videos by VICE

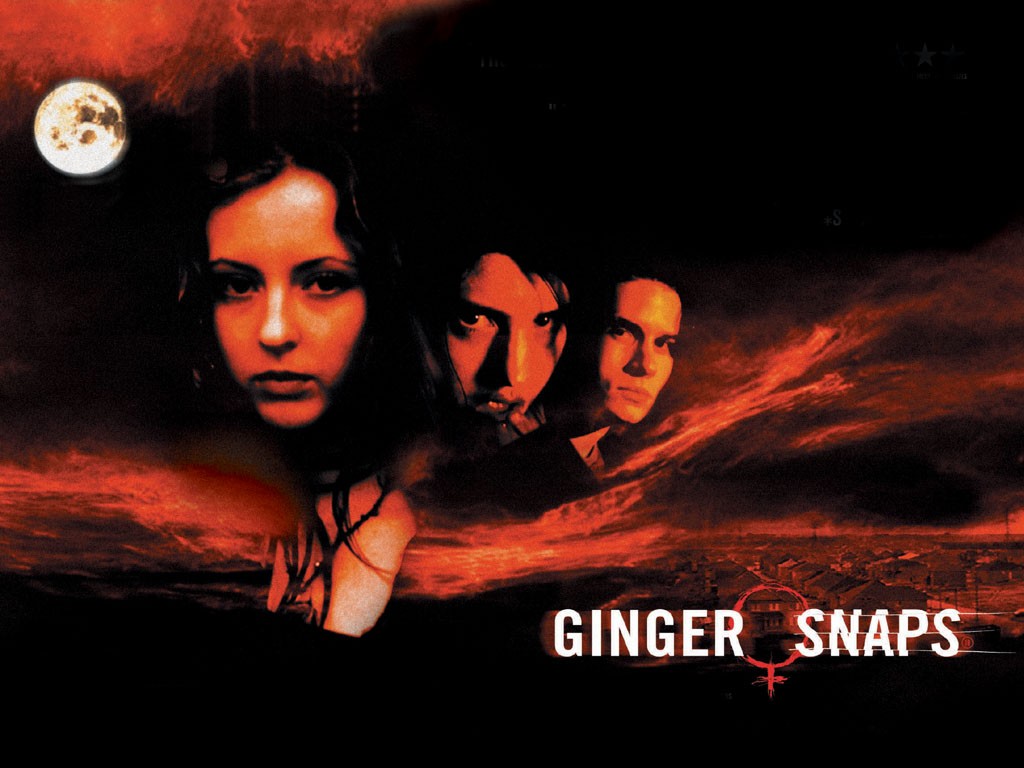

The film follows teen sisters Ginger and Brigitte Fitzgerald in the fictional Toronto suburb of Bailey Downs. Both are obsessed with death, staging and photographing their own gruesome demise, and repeating a mantra-like suicide pact: “Out by 16 or dead in this scene, but together forever.”

Ginger, now a fateful 16, is attacked one night by a werewolf and begins to transform, all while dealing with her tardy first menstrual cycle—the two transformative events blurring and combining into a single, gory process until Ginger finally, well, snaps. As Ginger begins to embrace her newfound gifts and appetites, Brigitte tries to find a way to save her sister, as well as their classmates, teachers, and local pets, all as the death toll keeps rising.

When she was first approached, screenwriter Karen Walton wasn’t immediately into writing horror, a genre that hadn’t been terribly invested in positive depictions of women and girls, but director John Fawcett encouraged her to write the film _she_’d like to see.

“I sat down with the idea that a lot of werewolf movies seemed very much the same. My favourite was of course An American Werewolf in London, because it was at least a little punk about it, but it was still two white dudes grappling with the beast inside of them,” Walton told VICE. “I love stories that work on a lot of different levels, for a whole bunch of different kinds of people. That it turned out to be OK in the marketplace as just one girl’s voice—and a director who really wanted to support that—is remarkable, I think, for the day.”

Ginger Snaps premiered August 1, 2000, at the Munich Fantasy Filmfest, before a festival run that included TIFF and SXSW. The film was instantly resonant and a standout among other horror films of the time. Scream had raised the bar for teen horror in 1996, and despite Scary Movie starting a cycle of spoofs in 2000, the genre still had some life left in it at the start of the new millennium. J-horror was starting to get big in North America, the first Final Destination film hit theatres, and weirder fare with indie sensibilities like Cherry Falls, American Psycho, and The Cell were keeping things interesting. But still, Ginger Snaps felt different. Ginger’s transformation and troubled relationship with her sister were relatable and evocative of teen alienation and suburban ennui in a way that felt particularly relevant and sincere.

Walton created instantly memorable, iconic characters in Ginger and Brigitte. Katharine Isabelle, who played Ginger, connected with her character right away. “When I first read this script, I loved it. I was 17. I hadn’t come across anything that was wickedly dark and funny and interesting and had such a great, multidimensional female character that’s going through some fucking shit, you know?” she told VICE. “She resonated with me, and I wanted to do that right away, immediately. I was obsessed with it… It was just so well written.”

Despite a limited release (it only made about $500K at the global box office), Ginger Snaps gained a huge following, in part likely thanks to a DVD boom. And it got a real boost from critics, who were overwhelmingly on board. Charles Taylor, writing in Salon, crowned it “the smartest and funniest scary movie in a long time” and called it “a true feminist horror film.” Scott Tobias at the A.V. Club called it “a smart, resourceful, and wickedly funny teen-horror film that reinvents the werewolf myth as a potent metaphor for pubescent angst and humiliation.”

The film’s feminist edge was a recurring focal point among critics, and it’s no surprise Ginger Snaps_’ cult following skewed female, a trend that held true for its sequel and prequel, both released in 2004. “It was before _Twilight; it was before this 20-year era of being fascinated with vampires and werewolves and supernatural stuff,” said Isabelle. “It was something new that girls hadn’t seen—this empowered supernatural creature that felt the same things they did.”

“I wanted to do a movie that women, and young women, could go see and enjoy, and return to or discover the genre from a different point of view than, at least in North America, I’d been exposed to at that age,” Walton explained.

University of British Columbia film studies professor and cult cinema scholar Ernest Mathijs told VICE that the feminist bent of the film and the predominantly female fandom stood out for him, making it a compelling object of study that he would eventually write a book about. “I think it was around the same time that female horror fans began to be noted more,” he said. “You can say they were always there, but the horror genre still has that tag, that label, that it’s a very masculine genre.” Or, as Walton put it, “Even though women and girls are superfans of all kinds of genres, it’s still considered, in some places, odd. And that’s too bad, because if anyone relates to the monstrous and the horrific, it would be most women, I think.”

Mathijs surveyed audiences of the third film and noticed that most respondents were girls and women. “They raved about the film,” he said. “That’s what made me realize that it was a groundbreaking franchise.”

It also didn’t hurt that werewolves were a relatively niche market, begging for a new entry. With a few iconic exceptions like The Wolf Man, The Howling, and An American Werewolf in London, werewolf movies don’t hold the same cultural space as vampire and zombie stories, especially not female werewolves.

But getting Ginger Snaps from page to screen wasn’t easy.

First the production team missed a deadline to apply for funding from Telefilm Canada, the nation’s federal film financing body. Once enough other cash had been acquired through piecemeal fundraising from producers, distributors, and broadcasters, the team had to wait another year to apply. That gamble paid off, but it also cost them a distributor.

Then, just as things were back on track and casting began, the horrific Columbine High School shooting happened in April 1999, followed eight days later by a shooting at W.R. Myers High School in Taber, Alberta.

Suddenly, fictional teens murdering one another took on a timely realism that turned some heads. Even more, Columbine brought on intense scrutiny of goth culture, with the teens responsible known for their black clothes and ubiquitous trench coats. A kind of mutated second-wave of the 80s and 90s “Satanic Panic,” this renewed moral panic surrounding goth aesthetics made Ginger Snaps even more of a target for worried parents and politicians—the Fitzgerald sisters’ morbid interests, their outsider status, their clothes, and their jewellery were all the kinds of red flags parents and teachers were being told to look out for.

This wasn’t some vague sense of unease from the general population, either, nor just a fear that audiences might not show up. The backlash posed a tangible threat to production.

“Casting Directors Boycott Toronto Teen Slasher Movie,” read one Toronto Star headline in June 1999. The story explored the effects of then current events on Ginger Snaps: “Shaken by recent high-school murders in Colorado and Alberta, six prominent local casting directors have refused to work on a teen slasher-werewolf movie planned for filming in Toronto in September.”

That meant that Vancouver-based Isabelle and Emily Perkins, who played Brigitte, got a shot at auditioning, which probably wouldn’t have happened without the backlash. “They would have just hired locally. That’s what low-budget independent Canadian movies do. It’s not really in their budget to fly out multiple actors and put them up in hotels or apartments,” said Isabelle, whose chemistry with Perkins is a huge asset to the film. “Emily Perkins and I were in the same agency; we’d actually known each other since we were really small kids. We were born in the same hospital, went to the same kindergarten and elementary school,” she said. “We had that really fun sisterly bond that lent to us portraying that onscreen. We were really comfortable with each other. We really let each other just have that relationship that you only get by knowing someone for years and years and years and years. She’s just the best.”

Isabelle and Perkins gained their own followings and become horror icons, and they’ve been self-reflexively cast together since, including as evil step-sisters in Another Cinderella Story. Isabelle has returned to the world of werewolves recently in Netflix’s The Order after other major horror roles in American Mary and Hannibal.

During pre-production, questions also came up about government funding for Ginger Snaps, as Telefilm had committed more than a quarter of the $4.2 million budget after the yearlong wait to apply. The move was controversial enough to elicit a statement from Telefilm’s director of operations, Bill House, quoted in the Globe and Mail. “I’m very disappointed by the reaction of the casting directors,” he said. “It’s by no means a teen slasher movie. It’s a genre picture. It’s a good script from reputable film producers.” The same piece quoted playwright and NDP culture critic Wendy Lill, who said, “In the best of all possible worlds, there will be a chill on the amount of violence rolling in on us… I don’t think anybody benefits from a steady dose of violence on TV and film.”

Walton, Fawcett and their producers held strong, but it was an odd battle to have to fight in the first place. “It was my very first and unwelcome introduction to how quickly impressions of what it is you do as an artist can be manipulated for the news of the day,” Walton said. “Of course, the entire tempest in a poorly-informed teapot had nothing to do with anything we had written or planned, or had been financed. This was a conflagration, and its actual intent—in terms of whoever decided to call all the newspapers—remains frankly a mystery to me,” she said. “But it’s rough when your parents call from Alberta and go, ‘What have you done?’ because Peter Gzowski on CBC Radio says you are a monster, and like, I wrote a movie about a werewolf. I’m really confused. I don’t really understand what the problem is.”

The film went forward, because Ginger Snaps, for one thing, obviously didn’t pose a threat to society. It was a well-told modern fable, instantly familiar to any teen just trying to get through their high school years. The film tackles the teen experience, all while telling a deeply personal story about two sisters and a family in transition—and like other films, shows, and video games, was hardly to blame for school shootings.

Anticipating Jennifer’s Body, which came almost a decade later and has justly gained its own cult following and renewed mainstream interest, Ginger Snaps powerfully evokes what it’s like when a close bond turns sour, with Ginger effectively threatening to leave Brigitte behind as she transforms, and exhibiting toxic and sometimes confusing behaviour toward her sister. “We’re almost not even related anymore,” Ginger says, while seductively trying to convince Brigitte to join her and revealing both a queer and incestuous subtext to their relationship, a subtext that leaves much room for interpretation.

And then there’s the central allegory tying menstruation to lycanthropy, with werewolf lore’s marriage to the lunar cycle perfectly positioned to make Ginger an iconic horror monster.

Menstruation as a stand-in for monstrosity is nothing new, from teen boys grossed out at the mere mention of periods, to cops not even knowing what tampons look like when (probably) spiking their own Starbucks orders, to Brian DePalma’s 1975 horror classic Carrie, the exemplary menstrual horror film par excellence, in which the titular teenager manifests supernatural powers when she’s ridiculed by her peers and chastised by her repressive mother after her first period.

But Ginger Snaps unpacks the weight of all that history and offers a tender response in the midst of all the carnage and body horror. It asks us to consider: What if Carrie had had a caring sister to offer an empathetic, supportive ear? What if her mom was willing to literally blow up their life and go on the run and protect her daughters—as the campy matriarch Pam (played to perfection by Mimi Rogers) does when she starts to catch on to what’s going on in her home?

In the end, Ginger’s fate isn’t much better than Carrie’s, but it paints a compelling picture of how society is to blame for making girls and women feel small, aberrant, and worthy of blame for every social ill, including their own bodily functions. Ginger is genuinely monstrous, so it’s not a neatly delivered message, but it’s not really supposed to be, either. It’s a messy film with lots to say, and it asks more difficult questions than it can or even wants to answer.

That’s probably why Ginger Snaps works so well, why it sticks with people and inspires such strong reactions. It’s less a blueprint than a broad social reflection, making fans feel seen and maybe understood a little bit. “I do think those characters spoke to the 15-year-old punk in a lot of people, and it really did speak a lot about being an outsider and deciding who your most fruitful relationships really should be with,” said Walton, who continues to be amazed at how strongly fans connect with the film, even 20 years on. “I’m now meeting the kids of the kids who first saw it, so that’s always fascinating, to see what another generation makes of it. What a lucky life I have had because I did a little werewolf movie. It’s very nice.”

“The fanbase is so amazing,” said Isabelle. “I think it was a touchstone for a lot of people, and it brought communities together. It brought groups of internet friends together. It bonded sisters and moms and daughters. If you can put out a piece of art in the world—even if you were 17 and didn’t know what the fuck you were doing—that had that impact, that is a blessing.”

Walton hopes the film inspires other first-time filmmakers to make the movies they want, and why wouldn’t it? Her experience and the very existence of Ginger Snaps are absolutely inspiring. “That would be the absolute best legacy for this little indie monster movie ever,” she said, “that a whole bunch of people see that and go, ‘Wow, if they can do it, maybe I can too.’ I would love to see all those movies.”

With two decades of hindsight, we probably do owe our gratitude to the talent behind Ginger Snaps for at least some of the continued weird brilliance of Canadian films, and Canadian horror specifically. It truly was one of our finest exports, and a big win for public arts funding.

Follow Frederick Blichert on Twitter.