Despite his reputation as a Brazilian jiu jitsu savant, Gunnar Nelson is one of the better examples of karate in mixed martial arts. The term ‘karate’ is even less insightful than the term ‘boxing’. A boxer can be a beautiful outfighter, a furious infighter, a dancing master, or a shuffling combination puncher and a thousand things in between. Karate can be a rough and tumble game of bareknuckle body punching and throwing up high kicks from chest-to-chest range, or it can be a glorified game of tag. Nelson is a great representation of the skills developed through training for the latter. Though it might be more helpful to consider knockdown karate as ‘full contact taekwondo’ and points style karate as fencing without the foil.

The problem with points style karate competition has always been that it treats all connections as equal. So a beautiful pulled right hand on the nose means every bit as much as Ko Matsuhisa spasmodic scorpion kick: a technique which is unlikely to hurt anyone except the man attempting it. Granted the points awarded for each may be different, but the fact that this kick scores as a strike hurts the entire game in the eyes of many.

Videos by VICE

Though while we are on the subject of scorpion kicks, it is not unthinkable that a fighter could do some hurting with a scorpion kick. The back kick of Yaw Yan, a Filipino kickboxing art, is essentially a step across scorpion kick. But there are plenty of other opportunities for forms of scorpion kicks, such as Erick Silva’s heels to the face of Takenori Sato as he clung to a single leg takedown attempt.

There are plenty of issues with the points karate style of competition if it is considered as the end in itself. No one is calling the best points karateka in the world the baddest man on the planet, after all. But using it as a training method, as a means, a fighter can learn to cover and create large distances with grace and ease which is easily one of the most useful skills to have in any form of fighting. He who decides the distance decides when the exchanges happen, and he can time his counters while conserving his energy. Think of the fits that Lyoto Machida gave the light heavyweight division before fighters started cottoning on and making him lead. Fighters couldn’t get to him when they wanted to, started over committing, and sooner or later he would stop retreating and they would run onto a car crash of a counter punch.

The world of competition karate is just so far removed from what we know as real fighting that it can be pretty hard to watch. For instance, this highlight seems to be a bunch of people prancing around in pajamas, posing when they think they’ve scored a point and feigning injury when they think the opponent has. But beneath the surface there are some nice angles, some stance shifts, some draws, and above all some very high level understanding of distancing.

The Lunge

When everything scores, no one can afford to hang about. So you will see the nice wide stance, with the centre of gravity far away from the opponent and the lead leg ready to push off and create distance at an instant’s notice. But when everyone is ready to run, some effort and cunning is necessary to close the distance. There are a dozen ways to close the distance or make the opponent come to you, but one which trick which is common in high level karate and has made a good few appearances in Nelson’s fights is to sneak up the back foot.

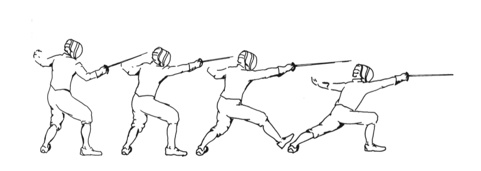

The back foot provides the drive to any advance. Similar to the lunge which is practiced millions of times by a world class fencer, closer to the opponent the fighter can get the driving point, the further he can lunge. Some karateka, such as Koji Ogata, simply start in a low stance and wave their hands as they draw their rear foot up underneath them. More commonly you will see fighters use bouncing and rhythm to hide their intended lunges. A fighter will bounce back, forward, and back again in the same stance, but as he comes forward again he will subtlely bring the rear foot underneath him in the air, often getting up onto the ball of that foot, ready to leap in further than the opponent expects is possible when he touches the ground.

From John Smith’s ‘Foil Fencing’

Ogata’s creeping method required him to stay low in his stance, because bringing the rear leg in while standing in a long karate stance would raise him up and clue the opponent into the fact that something was going on. When something looks odd in point fighting, the best option is to run and reset. The genius of bouncing is that the motion hides most of the tells that the fighter is preparing to lunge.

In this famous sequence from Gunnar Nelson’s fight with Brandon Thatch, you will notice how Nelson’s stance becomes considerably shorter with his back foot coming in underneath him and up onto the ball of the foot when Nelson is preparing to lunge. Notice also that Thatch thinks he is comfortably out of range until after the lunge has begun.

The nice thing about bouncing, rather than stepping, is that both feet can be moved in the same instance and land in a new position. The stance can be shortened mid bounce, or a fighter can bounce forward in his stance and immediately move out of it. The ‘forward, back, forward, lunge’ pattern repeats itself constantly in points competition. It is particularly effective if the fighter can draw his opponent into the opposite part of the ‘forward, back, forward’ dance. You will see this happen often in lower level competition, then one fighter’s lunge will fall on the opponent bouncing forward.

Though bouncing generally must be engaged in cautiously. Both feet move at once, however briefly, and you can’t change direction mid bounce. It is a case where your rhythm is literally visible to the opponent and you can’t do anything about it. Here Martin Kampmann breaks into a short back and forth bounce. He begins retreating as soon as his lead foot hits the ground after realizing that Johny Hendricks is lunging at him, but is just a fraction too late. Minor, minor stuff in the big scheme of things but a stern reminder that moving both feet at once comes with its own downsides

While karate competition can often be even more like fencing, with fighters lunging with a lead straight (kizamizuki), Nelson has been having good success with a slapping left hook. It’s an impure punch because his weight is springing forwards and he often stands side on enough that he cannot rotate his trunk fully into the blow, but it often sneaks around the guard and can allow Nelson to follow with the right straight as against Thatch.

Similarly you can see Nelson’s bouncing setting up his lead leg side kick here. Lead leg kicking in general can be misunderstood in terms of distance. The old Bruce Lee idea is that the lead leg side kick to the front knee is the longest weapon to the nearest target, but where the lead hand reaches further than the rear hand, in kicking the centre of gravity moves over the standing leg. It is affected not just by which striking surface is nearer to the opponent, but by which pivoting / anchoring point is. The lead leg is further forward so in kicking straight out of the stance, without moving the feet, many rear leg kicks can often reach further than their front leg equivalents. The lead leg side kick is a beautiful technique not just because of its length but because it puts the body on a line and takes the head away from the opponent, it also occupies the centre line so that they cannot simply step in during the kick, but to maximise the length of the strike some footwork needs to be done.

Here’s the great old school point fighter and early kickboxer, Joe Lewis talking about hiding the side kick with bouncing. Lewis sneaks his lead foot out, skips up to it and has hopefully covered the distance sneakily enough to catch the opponent cold.

But it’s not always necessary to skip up. Here Nelson’s back foot sneaks into the position it is going to be in to serve as the pivot leg, as he bounces forward in that familiar back and forth pattern.

Low Guard

There are many facets which differentiate a point karate style of fighter from a more traditional kickboxer or boxer or knockdown karate, but that covering of distance is the most important—it’s the first to the target, but that also means that karateka can get in the habit of bursting all the way in and hanging about in range afterwards. If you spend a few years practicing ‘selling the point’, it can be a hard habit to break:

And Nelson has occasionally had trouble with hanging around in the mid range after his right hand.

Rick Story spent his bout with Nelson eating rights at first, eating and returning his body shots later on, and finally simply throwing against a tired Nelson whose footwork could only be summoned in short bursts.

This is exacerbated by the low hands guard that point karateka use. In karate competition this is a matter of form: you can’t throw punches out of a boxing guard because the judges won’t score them. Traditional karate has the reverse punch come from on the hip, but in competition a karateka can get away with punching from the chest. But the nice thing about punching from a hands low guard is that it changes up the angles on the opponent and removes that subtle tell of a forearms up kickboxing guard—the fronts of the fists, ‘the barrels of the guns’, changing from pointing upwards to pointing at the opponent. It also seems easier for many fighters to connect their hips to their punches when they aren’t starting from a high guard.

Bruce Lee and others had speculated that a low guard uses the head as bait and hinders targeting of the body, but if the fighter with the low guard is aware that his head is exposed and acting as bait, as soon as his opponent steps in and the fighter isn’t in position to counter, his hands are going to fly up into a high guard anyway. Albert Tumenov stepped in on Nelson a couple of times as if to go high but instead attempted to hammer the Icelander’s ribs.

Where Gunnar Nelson has done well is in avoiding this middle range not by getting in-and-out, but rather in-and-in. Nelson has the old Emelianenko special (right hand, weave, clinch) down to an art form and hits it in almost every fight he wins.

Fedor himself, just because.

Nelson also repeatedly uses punch and clutch on the counter, when his lead hand is being dominated or he feels he is getting crowded.

Everyone knows, or should know, that there are positives and negatives to every method of fighting on the feet. There’s no one or guard or stance that protects a fighter from everything or one method which doesn’t have its dangers. Sneaking the rear foot up—sometimes planned, sometimes automatic in an experienced pointfighter ready to lunge—does allow the fighter to explode forward and cover a greater distance than his usual fighting stance would allow him to and to catch the opponent by surprise. But it also wedges underneath him like a sprinter in the blocks, he’s going to struggle to start retreating as comfortably as when he’s in his nice, long, bladed stance with his back foot pointing off to the side. Fighting with the hands low means that punches come in from unfamiliar angles, the shoulders and arms are exerted less, and when stepping into a range from which he can burst forward, the fighter gives his opponent no tells by bringing his hands into position before he starts striking. Yet with this energy consuming of bursting forwards it gets harder and harder to avoid getting caught in mid range as his feet slow.

Gunnar Nelson is not a particularly deep bag of tricks on the feet—he does what he does, and he does it damn well. He is a minimalist on the feet and his speciality plays into his tremendous skill on the ground, often compensating for his lack of a strong wrestling pedigree. And of course if you could hope to be good at just one thing in the fight game, distancing might be top of the list because if the other guy doesn’t come in with a plan to undo that, nothing he attempts will work. Such is the magic of that enormous buffer zone taught by point fighting.

Gunnar Nelson fights the methodical Alan Joubain this weekend in London in what might be the most anticipated fight on the card. It’s hard to predict anything in a fight, but with Gunnar Nelson you know that the burst will come—it is simply whether it gets his opponent underneath him or not, and that will likely dictate the outcome of the fight.